The road network of East Prussia history

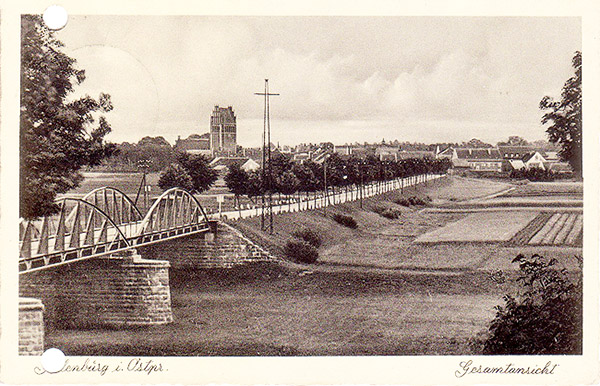

The road network of East Prussia began to form several centuries ago. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, many old roads were reconstructed and modernized, and have survived to this day almost in the same form as they appeared to travelers more than a hundred years ago.

The road, as an engineering, historical and cultural object, must be considered as a complex of structures consisting of bridges and viaducts, gas stations, signposts and chapels, which are, for example, an integral part of the roadside landscape in Warmia. In the Kaliningrad region, unlike Poland, insufficient attention is paid to the preservation of this cultural and engineering complex, to say the least: this complex is gradually being destroyed.

Below we publish a translation of the first part of Adam Płoski's article The Road and Its Surroundings, Evidence of Historical Changes in Warmia and Masuria (Adam Płoski Droga i jej otoczenie, świadectwa przemian historicalcznych na Warmii i Mazurach ), supplementing it with illustrative material.

The first roads

The road has always had a positive impact on the development of the economy of the places through which it ran, while also fulfilling military and administrative functions. In the Middle Ages, the road network created by the Teutonic Order in the territory of today's Warmia and Masuria connected castles and settlements, allowing for the development of trade. In the 16th – 18th centuries, this network expanded following the growth in the number of towns and villages, which was typical for the whole of Europe. New roads appeared, first of all, to connect administrative centers. Most of these new roads were of local importance and were distributed more or less evenly (with the exception of forested areas) across all populated areas. Important roads were laid between neighboring towns, and it was for such roads that entry city gates were built, which have survived to this day in some places (Pasłęk/Preußisch Holland, Reszel/Rössel, Kętrzyn/ Rastenburg , Nidzica/Neidenburg). Roads often influenced the architectural plans of towns and villages that arose along their route. Some roads, used among other things to transport troops from one region of East Prussia to another during military operations, even had the official designation of "military".

Historian Wladyslaw Szulist distinguished four types of roads in Warmia and Masuria in the period from the 16th to the 18th centuries, according to their functions:

- Transit roads – roads with high traffic density, connecting different countries;

- Roads connecting administrative centers;

- Roads connecting small settlements;

- Roads leading to individual private properties.

The most important international roads led, first of all, to Königsberg, which was connected with Danzig (Gdansk), Thorn (Torun), Warsaw. Transit roads had several variants of their passage, being at the same time of very mediocre quality, and often did not have a hard surface.

This is partly explained by the high traffic density not only of pedestrians (pilgrims, itinerant artisans, beggars), but also of horse riders and shepherds who used these roads to drive animals. Road repairs were mainly carried out only during the construction of bridges. The Prussian authorities began to pay attention to the roads only in the second half of the 16th century, issuing several so-called "road decrees" (Wegeedikte) in 1587, 1588, 1591 and 1592.

But despite these decrees, the technical condition of most Prussian roads was deplorable. The Königsberg-Braunsberg (Braniewo) road was also in poor condition, despite the fact that back in the times of the Order it had been equipped with ditches and ramparts along the roadsides. Later, during the time of the "Great Elector" Friedrich Wilhelm, work was carried out along this road in 1684 to clear roadside ditches, renew bridges and lay logs on the roadway, but its condition did not change dramatically.

In 1693, the first road construction manual was published in France. Together with the previously published instructions and treatises on roads and their construction, this led to a kind of revolution in this area. The first public transport for intercity transportation appeared in France – the mail stagecoach (at the same time, there is information that the first mail stagecoaches appeared in England in 1640. – admin ). In 1741, the School of Bridges and Roads (École nationale des ponts et chaussées) opened in Paris – the first state technical educational institution of its kind in the world (an error with the date, since this educational institution was opened in 1747. – admin ) . The result of all this was the emergence of new equipment for road construction, which, in turn, led to the introduction of new approaches and standards in this matter. Other European countries followed the example of France.

The role of post in the development of the road network

Prussia also drew on the experience of France in road construction, using its own building materials and local labor. Road construction in earlier times was hard work, often involving prisoners. During the reign of the successor of the "Great Elector", Friedrich III (1657-1713, from 1701 King of Prussia under the name of Friedrich I), attitudes towards roads were changed by a decree introducing severe sanctions against those who evaded road construction and maintenance work. It also spoke of the need to maintain roadside ditches in good condition to prevent water from accumulating in them. However, the greatest impact on the quality of roads came from the post office and the state's efforts to maintain the main postal routes along which regular mail was carried out.

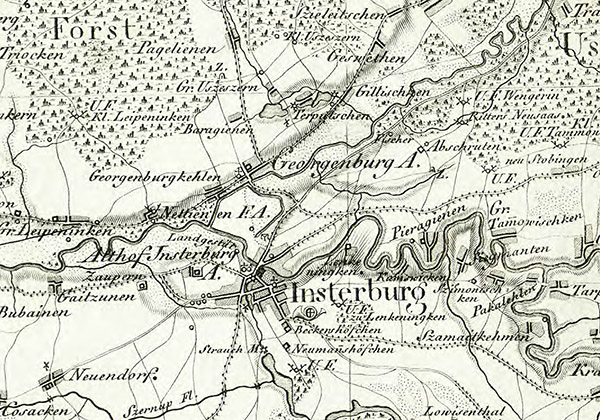

Post stations appeared along the roads. They had to be easily accessible, safe for travelers and have a certain set of amenities, so they were given special attention. Among the main postal routes in the territory of East Prussia, the following can be noted:

Königsberg – Preussisch Eylau (Bagrationovsk) – Bartenstein (Bartoszyce) – Heilsberg (Lidzbark Warminski)

Koenigsberg - Pillau (Baltiysk)

Bartenstein – Schippenbeil (Sempopol) – Rastenburg (Kętrzyn) – Peitschendorf (Pecki) – Ortelsburg (Szczytno).

The orders, instructions, and acts issued by the postal department in the future in one way or another concerned the condition of roads, roadside ditches, bridges, post stations, etc., but despite all these efforts, the condition of the roads practically did not improve.

In Warmia, the initiator of the creation of a postal service was Bishop Ignacy Krasicki. The bishop's post appeared in 1768. Its stagecoaches ran twice a week. Sending letters within Warmia was free. The bishop's post lasted only four years, ending after Warmia was annexed by Prussia in 1772. Friedrich Wilhelm III, King of Prussia from 1797 to 1840, as part of the unification of Polish and Prussian lands, ordered an inventory of the postal network in 1800, measuring all postal routes and installing milestones along them. However, this work was only completed 15 years later.

The 19th century, in addition to intensive road construction, was also characterized by the fact that the post office (which by that time had become one of the main users of the road network) moved away from transporting people to its current function – transporting letters and parcels. The arrival of a mail coach in the city, however, still remained one of the main events for the city dwellers, since along with letters, the postmen also brought news from the “distant world”. But the horse mail, having reached its peak by the middle of the 19th century, was later supplanted by the railway.

A turning point in the construction of state roads

The state of roads in the state has always interested rulers in one way or another. So King Friedrich Wilhelm I issued an edict on August 20, 1720, in which the improvement of the state of the road network of Prussia was declared one of the state priorities. This decree provided for the reconstruction and expansion of bridges, the installation of road signs, and determined the need for repair work in the spring and autumn to maintain the condition of existing roads. Severe punishment was determined for improper performance of road maintenance work. Officials responsible for the maintenance of state forest lands were obliged to provide timber for such work. The condition of roadside ditches was determined by special decrees.

During the wars with Napoleon, several orders were issued in East Prussia, which required monitoring of the condition of the roads used to transport troops to the east. But even these measures did not greatly improve the condition of the roads along which the troops and their accompanying convoys moved. Similar orders were issued after the end of the war in 1814, 1815, 1820, 1821.

Revolutionary changes in road construction began in the 19th century. The turning point in this field was the work of John McAdam [1] “Remarks on the Present System of Road-Making”, published in 1820. It proposed new solutions in road construction technology (use of hard road surfaces), reducing the cost of road works, as well as their duration (due to the use of mechanization).

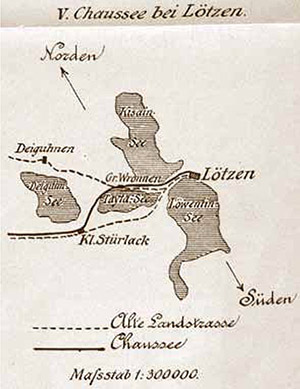

In Prussia, MacAdam's innovations were met with skepticism. Here, the road construction system used was that of the French engineer Pierre Tresaguet [2], developed by him in 1775. In 1834, at the provincial council in Königsberg, it was decided to expand the network of roads connecting the province with the Polish coast and the Kingdom of Prussia. Merchants and travelers coming to the province constantly complained about the poor condition of the roads. For example, it took 6 hours to get from Rössel to Sensburg (Mragowo) (the distance between these cities is about 27 km. - admin ), since the road was covered with potholes and bumps. It was believed that the Prussian king deliberately did not repair the roads in order to create difficulties for the enemy in moving his troops. Local residents also complained about the disgusting condition of the roads. Count Karl von Lehndorff [3] in 1830 described one of his trips along the roads of the Lötzen (Gizycko) region as follows: “The roads were no different from frozen plowed fields. […] I was forced to walk most of the way.” However, there are also references to the fact that the condition of the Prussian roads at that time was satisfactory.

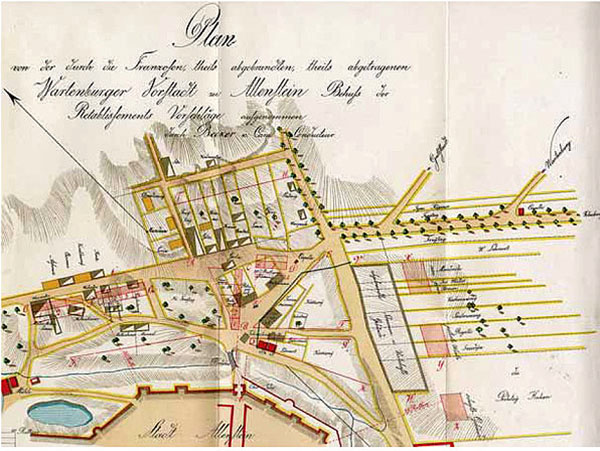

In 1834, Prussia issued instructions governing the design and construction of roads. The width of a road was determined by its purpose. Roads with little traffic had to be between 6.5 and 9.5 m wide (with a hard road surface width of 4 m). The maximum load of carts on the road was not to exceed 7,000 kg. To maintain the road network in proper condition, a special road service was created and a toll was introduced for travel on roads for their subsequent repair. The average cost of building one mile of road (approximately 7.5 km) in Prussia was 11,000 thalers. Following this, intensive development of the road network of East Prussia began, which continued until the beginning of the last century and was completed only with the beginning of World War II.

Most of the funds for the development of the road network came from the state. But investments also came from joint-stock companies, rural communities, magistrates and even private individuals. The state encouraged district administrations to build and reconstruct roads, partially subsidizing their costs. In 1902, the size of these subsidies was increased. In the districts, administrations for the construction and repair of roads were created.

Since 1875, the legislation concerning the construction of roads and their ownership was changed in Prussia (the so-called Dotationsgesetz Act of 8 July 1875), which completed a certain stage in road construction. All existing roads were transferred to provincial administrations, which were charged with their maintenance and service. Some roads were transferred to district and county administrations. The state tax for road use was abolished. The Oberpresident of the Province of East Prussia supervised the construction of roads passing through several districts. In the district of Allenstein (Olsztyn), according to the situation in 1910, roads were divided into classes depending on their "usefulness" (I-IV), depending on their form of ownership (state, municipal, private), as well as the possibility of military use (A and B).

Meters, kilometers, parameters

In the 19th century, following the Prussian provinces that had already built paved highways, East Prussia also began a thorough modernization of its roads. The first such cobblestone highway was the section from Königsberg to Elbing (Elbląg), the construction of which began in 1818. Then the highway (later called the "Berlinka") was extended to Marienburg (Malbork), and further west (even now on the "Berlinka" - today's road No. 22 - there is a section several kilometers long with a cobblestone surface, located a little west of Malbork. - admin ). This highway formed the axis of the entire road network of East Prussia. This network expanded slowly (the Königsberg-Elbing section took 10 years to build), largely due to the high cost of construction, which exceeded similar costs in Western Europe at the time. In the mid-19th century, the cost of building 1 km of highway in Western Germany averaged 5-6 thousand marks, and 12 thousand marks on particularly difficult sections, while similar costs in East Prussia averaged 15 thousand marks.

The difficulties were also caused by natural factors – the marshy terrain and

the presence of a large amount of sand and clay under the soil, which is why the

highways often had to be built anew.

Long construction periods were also typical of other East Prussian highways. The

Elbing – Osterode (Ostróda) highway, begun in 1829, was not completed until

1853. The Bartenstein – Opalenitz/Opalenitz highway (via Bischofsburg/Bistynek,

Ortelsburg, Willenberg/Wielbark) also took a long time to build, from 1835 to

1864. An exception here is the Königsberg – Tapiau (Gvardeysk) – Tilsit

(Sovetsk) road, built on the special orders of the king in just two years

(1830-1831). An unfavourable situation developed around Angerburg (Węgorzewo),

to which the highway from Gerdauen (Zheleznodorozhny) was decided to be built

only by a special order of the minister on October 6, 1856, after the project

was approved by the king himself. But, despite the difficulties, the road

network in East Prussia was steadily expanding. In 1826, there were only 52.5 km

of highway, in 1838 already 413.5 km, in 1853 - 902.75 km, 1862 - 1197.75 km,

and in 1874 - 1535.17 km. In most cases, trees were planted along the roadsides.

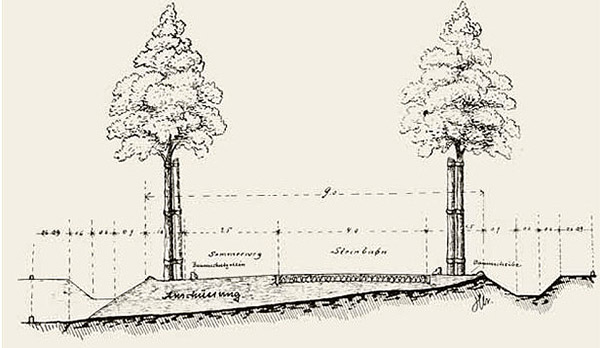

The highways that were built did not have a uniform surface. Next to the central roadway, laid with crushed stone or cobblestones (Fahrbahn), there was a narrower roadway without a hard surface - the so-called "summer road" (Sommerweg). Sometimes special areas were additionally arranged along the roadsides, where materials for subsequent routine repairs of the highway were stored. Over time, it was empirically concluded that the road should not be very wide. Its optimal width can be from 4 to 6 m, with a hard surface width of 2.5 m. This made it possible to reduce construction costs. The first highways built in the 19th century had a surface of gravel poured onto a base of broken stone, or from several layers of broken stone. Most of the roads were covered with gravel, as this greatly reduced construction costs. There were also cobblestone roads. After the First World War, the annual maintenance of a cobblestone road cost 500 marks, while a gravel road cost 300 marks. In 1910, there were 20.5 km of paved roads per 100 square kilometers of East Prussia. 60-80 such roads were put into operation annually. Before the Second World War, roads with the then new asphalt surface began to appear in large numbers in East Prussia. Small sections of asphalt roads began to appear here as early as the 1920s. At the beginning of the 1930s, there were 270 km of asphalt roads. The use of asphalt in road construction at the beginning of the last century was caused to a large extent by the advent of motor vehicles, the use of which on gravel roads was problematic.

Notes:

1. John Loudon McAdam ( 1756 - 1836) - a Scottish engineer who developed a technology for building roads with a hard surface made of crushed stone, which later became known as "macadam" after the inventor. Over time, this technology was improved by using tar, which binds the crushed stone. This surface became known as "tarmacadam" or "tarmac" for short ( tar - tar).

2. Pierre Trésaguet (1716 – 1796) – French engineer, pioneer of road construction. The method of road construction he proposed involved creating two layers of road: a base of large stones, onto which a layer of small stones was poured.

3. Karl von Lehndorff ( Karl Friedrich Ludwig von Lehndorff , 1770-1854) - Count, Prussian Lieutenant General, hero of the Napoleonic Wars. Owner of the Steinort (Sztynort) estate. One of the forts in the Königsberg fortification belt was named in his honor.

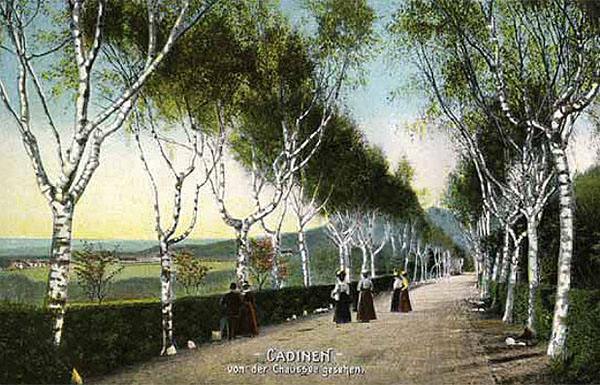

Roadside alleys

It is believed that Europeans began planting trees along roads after Marco Polo returned from China. The Kaliningrad region is strikingly different from the rest of Russia not only by its red tile roofs. Everyone who visits our region first of all pays attention to the roads with trees growing along the sides.

We offer a translation of the second part of Adam Płoski's article about the roads and roadside alleys of East Prussia "The Road and Its Surroundings, Evidence of Historical Changes in Warmia and Masuria" (Adam Płoski Droga i jej otoczenie, świadectwa przemian historcznych na Warmii i Mazurach ). The article is published with minor abbreviations.

Roadside alleys are a feature of the region

As early as the 13th century, the then ruler of China ordered trees to be planted on both sides of the roads, two steps away from the roadside. Damage caused to roadside plantings could be punished by death. Of course, not all Chinese inventions were adopted by Europeans, but roadside trees took root in Europe. The Italian architect Andrea Palladio [1] in his work “Four Books on Architecture” (I Quattro Libri dell'Architettura, 1570), among other general architectural principles, recommended planting trees along the roadsides, since they provide shade, decorate the surroundings and give pleasure to the soul.

The problems of regular plantings along roadsides were not initially a subject of special attention in Prussia. As early as the 17th century, trees were used only to mark the boundaries between parishes or villages. Later, local roads, which were the majority at that time, began to be planted with willows along the roadsides. The impetus for this was the decree of Friedrich Wilhelm I (1713-1740), who was the first of the Prussian kings to pay attention to the problem of planting trees along roads. But the most complete instructions on the rules for planting trees (a separate paragraph was devoted to this issue) were contained in the decree of Friedrich the Great (1740-1780) of June 24, 1764, according to which willows or other trees were to be planted along the roadsides of local importance, postal routes and roads of national importance, including military ones.

From then on, most roads with trees planted along them were called by the French word "alley". Punishment was imposed for the destruction of roadside trees. A year later, a decree on the planting of forests was issued, which also paid attention to roadside trees. According to it, the choice of tree species for planting was the prerogative of the local administration, which was given the opportunity to choose from several species: oak, linden, birch, willow and poplar. The width of the road was determined at 20-30 feet (6-9 m). There were to be ditches on both sides. Instructions from 1814 and 1834 determine the distance between trees along the roadsides. The first says 18 feet (approx. 5.5 m), the second - 10-35 feet (approx. 3-11 m). It was also ordered to install stone barriers along the roads so that carts and wagons would not damage trees.

Numerous local circulars issued in different years defined requirements for road maintenance (1850, 1853), and also ordered, among other things, road owners to draw up annual plans for their repair and establish the degree of punishment for the destruction of roadside plantings.

Issues related to roadside trees were also addressed in regulations and orders of departments not directly related to them. For example, the law on telegraph lines (Telegrafenwegegesetz) of December 18, 1899, regulating their construction, prescribed the utmost care for roadside plantings, and in the event of damage to them, the state was obliged to compensate the owner of the land on which the trees were planted. In 1911, a decree concerning the roads of the province of East Prussia (Wegeordnung für die Provinz Ostpreussen) was issued, which defined requirements, including for the planting of trees along roads. Control functions for the implementation of this decree were assigned to the traffic police.

Particular attention was paid to the issue of liability for damage to roadside trees. According to the order of Friedrich Wilhelm I (1731), those who intentionally damaged trees were subject to punishment in the form of forced excavation work to build fortifications. Later, in 1797, a fine was imposed for damaging a roadside tree (on the contrary, anyone who reported the offender was entitled to a reward), the culprit was put in stocks and obliged to compensate for the damage with work. In special cases, the culprit was tied to a pillory (from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m.), and a sign in German and Polish with the inscription "tree wrecker" was hung around his neck. The culprit was also obliged to plant exactly the same tree. Later, the punishment became only a fine of 5 thalers for each damaged tree (1840).

Trees were planted along roads primarily for practical reasons, so that travellers would not lose their way in the dark and troops moving along the roads would have shade. Krzysztof Celestyn Mrongowiusz [2] wrote the following in his poem in 1835: “… Without trees it is bare / Sad / On the road the sun blinds the eyes…” (Bez drzew goło, / Niewesoło, / W drodze słońce bije w czoło). In winter, trees protected roads from being covered with snow. They reduced the “monotonousness” of the journey, thereby reducing fatigue. This primarily applied to travellers on foot.

Roadside plantings on the so-called Schrötter maps [3], created in 1796-1802, are already marked along postal routes and main roads. Based on detailed field measurements carried out by a team of cartographers, they are considered the most accurate maps of northern Prussia and Poland in the early 19th century, and serve as an invaluable source of information on the condition and density of the road network of that time in the territory of Warmia and Masuria. The maps show many objects that in one way or another formed the road infrastructure - roadside inns, inns, bridges, etc.

Alleys to a certain extent formed and protected the roadside landscape in a natural way. In 1822, the Union for the Development of Horticulture was founded in Prussia, which aimed to improve the landscape, including the arrangement of alleys.

In the mid-19th century, work began in France to select tree species that were best suited for forming alleys. The first private nursery with trees for planting alleys appeared in Berlin. Trees became an important part of the landscape and human habitat not only in East Prussia. For example, in the permit for building a house in Żabno (a territory of Poland that was once part of Austria-Hungary), in addition to the standard requirements, there was an order to plant trees as densely as possible around the house.

The planting of mulberry trees, the seedlings of which were imported from China, was encouraged in Prussia at the state level. But in East Prussia this did not produce any significant effect (although old mulberry trees can still be found here and there in Kaliningrad. — admin ). Even a special decree from 1742 did not help, according to which a multi-year subsidy was due to those who created a mulberry nursery or began to grow them. In addition, instructions were developed regulating the planting of trees in villages and, among other things, requiring homeowners to lay out gardens and plant pussy willows and willows near their homes. It was also prescribed to plant trees along the boundaries of property (Dorf Ordnung, 1723).

Almost all new roads built in the 19th century were planted with trees. According to existing regulations, the owner of the land through which the road passed was obliged to constantly maintain roadside ditches in proper condition, plant trees and install stones along the roadsides to protect trees from damage. In accordance with the decrees of Friedrich Wilhelm IV of February 16, 1841, the reconstruction of old roads was to be carried out, if possible, with minimal damage to roadside trees. It was prescribed to avoid cutting down trees. It was proposed to use linden, oak, chestnut, birch, poplar, etc. for new plantings. At the same time, poplars were supposed to be planted at some distance from the roadside due to their shallow root system, which could damage the road surface. At that time, these trees were very popular and were planted not only along roads.

Road construction specialist and professor at the Polytechnic Institute in Lviv, Artur Kühnel, wrote that poplars stand out against the surrounding landscape and mark roads very well. Their appearance from afar promises a traveler shelter and a place to stay, showing the way to them. It is necessary to preserve the healthiest and most beautiful specimens of trees in memory of history. (Here, one can pay attention to the fact that the position is put forward about the need to protect trees out of respect for their past and tradition.)

On the basis of the decree of October 14, 1854, permission was granted to plant fruit tree alleys. In Prussia, it was proposed to plant fruit trees along roads as early as 1752. Fruit trees were planted especially often along the roadsides in the immediate vicinity of settlements. Road owners often leased the roadsides for planting fruit trees along them, thereby shifting the responsibility for the condition of the alleys to the lessee. Obviously, fruit trees could bring material benefits to their users. Advertisements for the lease of fruit alleys were not uncommon in the local press of those years. For example, in 1878, the newspaper "Allensteiner Kreisblatt" placed an advertisement for the lease of an alley of cherry trees near the village of Nickelsdorf (Nikelkowo) by the authorities of the Krais Allenstein (Olsztyn). There are also advertisements for renting out roadside ditches, on the slopes of which it was possible to mow grass. Not quite typical for East Prussia was the road along the Curonian Spit, on the sides of which pine trees specially brought from Spain were planted to protect against sand.

In the 19th century, the rapidly expanding railway network began to compete with the roads. At the same time, new access roads to the railways were built, which led to the expansion of the road network. And, in accordance with tradition and regulations, trees were also planted along the sides of these access roads.

Roadside alleys were protected by the state. The local press published advertisements calling for monetary rewards to inform on those who deliberately damaged trees. District departments published collections of orders and instructions for specific officials regarding road maintenance. They often contained provisions concerning alleys. Road services, which were responsible for bridges, roads and roadside plantings, were charged with maintaining alleys.

In the 1920s, alleys, as paradoxical as it may seem from today's point of view, served a traffic safety function. The trunks of roadside trees and protective stones were painted white at the level of the light beam of car headlights. The widespread use of cars became the reason for the expansion and modernization of roads. By this time, the issues of organizing roadside plantings had a solid theoretical basis. Specialized literature on road construction was published. Researchers in the field of roadside alleys recommended planting the following tree species: elm - a first-class tree for forming alleys with a straight trunk and a wide, dense crown, birch, which was also excellent for these purposes, as well as oak, linden and ash. In East Prussia, tree planting events were often organized by schoolchildren. One- and two-year-old seedlings grown in special nurseries were used. The cost of planting one such sapling was 2.64 marks, while the cost of saplings (for example, silver linden) reached 4.5 marks. Thus, the cost of planting one sapling of the most common species before the First World War was from 4 to 8 marks. The maintenance of each planted tree (watering, pruning, fertilizing) cost 25 pfennigs annually. Compared to others, such costs did not seem too high. Permission to plant trees was issued by the official responsible for the condition of the alleys. His duties included conducting an annual (in August) inspection of all roadside plantings, as well as monitoring them in the fall and early spring. At the same time, new alleys were planted.

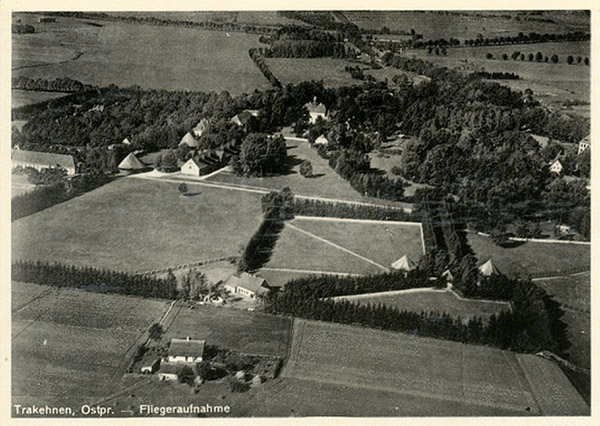

The construction of state roads in East Prussia was primarily due to military and economic reasons, but attention was also paid to satisfying the needs of the post office and residents of the territories for new roads. The construction of new roads was accompanied by the appearance of new alleys and the renovation of old ones. This continued until the 1930s. Similar measures were also carried out by private landowners, laying out private alleys to their palaces, estates, manors and railway stations.

As a traveler who visited Masuria in 1896 noted, "... all the roads here, without exception, are lined with trees. A sense of respect for trees is instilled here from school, and at every step you come across signs nailed to the trunks reminding you that a kind person will not harm a tree."

Roads of Warmia and Masuria after 1945

After the annexation of part of East Prussia to Poland, changes occurred in the road network. Part of the road infrastructure was destroyed, as the Wehrmacht troops destroyed bridges behind them during their retreat, and some roads changed their meaning. The new inhabitants of Warmia and Masuria, however, realized the importance of roadside alleys for the landscape, understood that the venerable lindens, maples, and birches growing along the roads give the area a unique charm and are strikingly different from the dull landscape of flat plains devoid of woody vegetation. This was also helped by legislative norms, which formulated the postulate that the purpose of planting roadside trees is the cultivation of beauty in road construction. A road can become both a destructive factor in the surrounding landscape and a creative one. A correctly planted alley is a decoration of the landscape, creating a transition from the natural landscape to the correct architecture.

At various times, more than 100 million tree saplings and 60 million shrubs were planted in Warmia and Masuria as part of the afforestation program. In addition to special services, scouts [4], schoolchildren, and workers from collective and state farms took part in these events. In addition, all new roads in Poland were obligatorily lined with trees along the sides.

Notes:

1. Andrea Palladio ( Andrea Palladio , real name Andrea di Pietro, 1508 - 1580) - an outstanding Italian architect, the founder of classicism, the author of works on architecture. He worked mainly in Venice and Vicenza.

2. Krzysztof Celestyn Mrongowiusz (1764-1855) - Polish philologist, translator, Lutheran pastor.

3. Friedrich Leopold Reichsfreiherr von Schrötter (1743-1815) - Prussian minister, chief president of the provinces of West and East Prussia. Under Schrötter's leadership, maps of East and West Prussia were compiled and published in 1796-1802 on a scale of 1:50,000 ( Karte von Ost-Preussen nebst Preussisch Litthauen und West-Preussen nebst Netzedistrict 1796-1802 ).

4. Scouts - The Union of Polish Scouts ( Związek Harcerstwa Polskiego, ZHP) is a youth scouting organization that has existed intermittently since 1910 to the present day.

Sources:

Bildarchive