History of brick production in East Prussia

Brick as a building material has been known since ancient times and was widely used by civilizations in Mesopotamia and Egypt, and later in the Roman Empire.

In Europe north of the Alps, the technology of brick production, forgotten after the fall of Rome, re-enters the territory of Lombardy around the middle of the 12th century [1]. A century later, brick is already quite widely used in construction in Western Europe.

In the territory of the Teutonic Order, the first information about brick production dates back to the 1240s and refers to Elbing, when in 1246 the Dominican monks received permission from the Grand Master of the Order, Heinrich von Hohenlohe, to build a brick church. At the same time, the bricks were to be produced outside the city itself [2]. Therefore, it can be assumed that the production of bricks in the Order began almost immediately after its appearance on the Prussian lands. This was largely facilitated by the fact that in the lands conquered by the Order, wood was practically the only available material for construction. Stone (primarily easy-to-process sandstone and limestone, widely used for religious and castle construction in Western and Southern Europe) is, as they say, not found in Prussia. The boulders that were once brought here by the Valdai glacier do not form deposits and are not found in any significant quantities. They usually appear on the surface during plowing of fields or development of sand or clay quarries. Accordingly, in order to collect at least some more or less marketable quantity of this fieldstone, a certain amount of time is required. Of course, boulders could be found along river beds, but this only confirms the fact that fieldstone could not become the main building material and could be used at most for the construction of foundations. At the same time, the use of wood for the construction of order fortifications already at the initial stage of "Drang nach Osten" showed that the knights who hid behind a wooden palisade from the raids of the Prussians were not safe, since the attackers simply burned this very fortification. In addition, wood is much less durable than brick.

Therefore, the Order had no other choice but to start using bricks to strengthen their fortresses, to build defensive walls for the cities they founded, and to build religious buildings, primarily churches, in which, among other things, German colonists and loyal Prussians could, if necessary, sit out an enemy raid. And the literally ubiquitous distribution of excellent quality clay deposits and the relative ease of its extraction (a couple of shovels are enough - and here you have a ready-made quarry) only contributed to the appearance of bricks.

The process of making bricks has changed little over the long history of its use in construction. Of course, brick factories now have modern equipment, machinery, tools and technologies, but in general its production still consists of four main stages: preparation of raw materials, molding of raw bricks, their drying and firing in a kiln. And if now an excavator works in a clay quarry, then earlier, as we have just pointed out, people dug clay with shovels, and instead of cars or trolleys they used horses harnessed to carts.

In this article we will talk about bricks and their production in Prussia from the time of the Order until the beginning of the 19th century, when the industrial revolution began, which affected, among other things, the brick industry.

First, let's sort out the terms.

Brick is an artificial stone made from natural mineral materials, having a regular shape and used for construction.

According to the source material, bricks are divided into ceramic and silicate . Ceramic bricks are made from clay, silicate bricks are made from a mixture of quartz sand and lime.

Most often, we see fired ceramic bricks around us (usually red). But unfired adobe bricks appeared earlier and, surprisingly, are still used today.

Bricks are also divided by purpose (building, facing, shaped, clinker, fireproof), by molding method (manual and machine molding) and by filling (solid and hollow).

In addition to bricks, we will also mention ceramic roofing tiles , the manufacturing process of which is similar to the production of ceramic bricks. Ceramic tiles can be divided by the molding method into manual and machine, and by shape they are divided into flat and wavy. There are also special types of tiles, such as ridge tiles.

Brick production: raw materials and technology

How was brick production organized during the time of the Order and then over the course of several centuries?

Although the production of bricks in the Prussian lands dates back to the early times of the Order, it is obvious that until the Order had finally consolidated its position in the conquered territories, there was no talk of any large-scale production and use of it as a building material. This was influenced by two factors: the unstable military and political situation associated with the suppression of the uprisings of the Prussian tribes by the knights, and the lack of craftsmen who could organize the production of bricks, since the Prussians had no tradition of brick construction. Therefore, we can only talk about the widespread use of bricks by the Order starting from the last decades of the 13th – early 14th centuries, approximately when the construction of Marienburg Castle began. It was at this time that the Order actively attracted colonists from various regions of Germany to settle the conquered western Prussian lands (the colonization of East Prussia began several decades later), and, obviously, recruited both brick masters and masons. It should be noted here that both bricklayers and masons, unlike many other craftsmen, did not have their own professional workshops. Most likely, these craftsmen moved from construction site to construction site, not being tied to a specific location. Certain stylistic features of brick buildings in Prussia and some characteristic forms of the bricks used for them indicate that the bricklayers and masons came from Mecklenburg, Vorpommern, Brandenburg and Lübeck [2]. The fact that the construction work was carried out by skilled craftsmen is evidenced by the buildings themselves, demonstrating a high level of quality of both the brick itself and the brickwork.

To organize brick production, it is necessary to have, first of all, reserves of clay of the appropriate quality, a kiln for firing raw bricks, and fuel for the kiln. Water is also necessary to prepare the clay mixture, but its availability is not a determining factor for the localization of brick production. The customers of the construction therefore had to determine whether they needed to organize brick production near a specific construction site to reduce costs, or whether it was easier and cheaper to bring ready-made bricks from the nearest brick factory. Obviously, for large objects it was cheaper to organize brick production on site. For small objects, this also made sense if there were clay deposits nearby. In this case, the costs of building a kiln for firing bricks compensated for its delivery to the construction site.

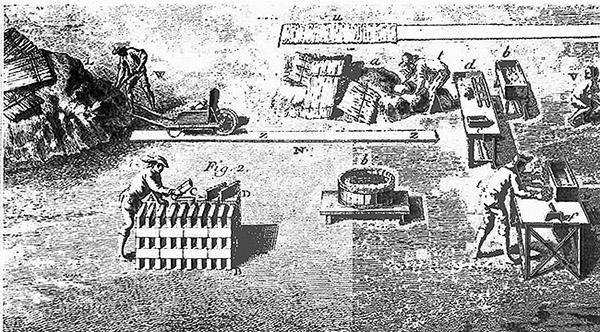

Clay mined in a quarry for brick production had to lie in the open air for quite a long time (up to two years), exposed to precipitation, heat and cold. During this time, a kind of "fermentation" process took place: easily soluble salts were washed out of it, organic matter (roots, etc.) rotted and was also washed out, and moisture was evenly distributed throughout the entire mass of clay raw materials, and ultimately the clay acquired the necessary plastic properties. Then the clay was placed in a shallow pit, water was added and they began to knead it either with feet or using horses. When kneading the clay, stones and other inclusions were removed from it, sand was added if the clay was too greasy. Gradually, a homogeneous, very thick mass was formed. This took from 12 hours to two days [3].

Then the clay was delivered to the molding tables, where the master, using a special wooden form, molded the bricks. The molded bricks were placed under a canopy, where they dried for several days. The dried bricks were placed in the kiln for firing in rows in a special order (herringbone). At the same time, for an even distribution of heat inside the rows, gaps of 2-4 cm were left between the bricks. After placing the adobe in the kiln, its arch was sealed with defective bricks from previous firings, covered with clay and earth. In the kiln, the adobe, exposed to temperatures from 850 to 950 ° C, turned into the very same red ceramic brick that gave the name to the entire architectural style - brick Gothic. Firewood, peat, coal, reed and even straw were used as fuel for firing. The firing process was quite lengthy - up to two weeks (its duration depended on the weather, the degree of humidity of the raw brick and the quality of the fuel for the kiln) and consisted of several stages: drying the brick, when a relatively low temperature was maintained inside the kiln, its actual firing at a high temperature and subsequent cooling. The first two stages were especially important, since the master was required to control the degree of heat inside the kiln to prevent swelling or cracking of the bricks.

Firing was carried out only during the warm season, so in the early stages of its development there was no continuous cycle of brick production.

After firing, the bricks cooled for a few more days. The cooled bricks were removed from the kiln and after being rejected, they could be used for construction purposes.

Until the end of the 18th century, bricks were fired in so-called "field kilns", the design of which, by and large, remained unchanged for centuries and which we will discuss below. Despite the grandiose scale of brick construction in Prussia in every sense, and the associated brick production, it is surprising that to date archaeologists have managed to find only a few pieces of evidence of brick production dating back to the times of the Order.

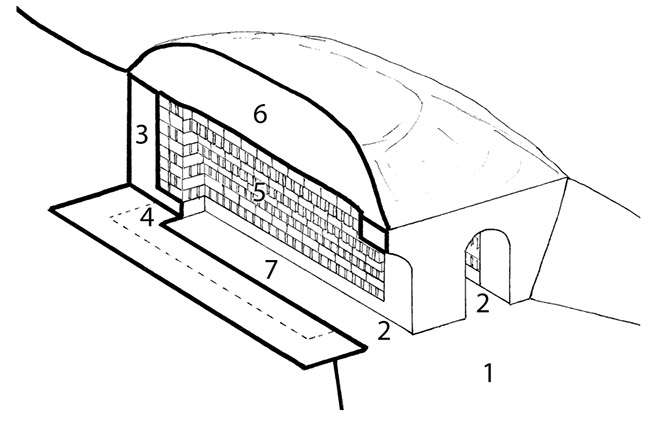

In 1908, a brick kiln was discovered in a cemetery near a church in the village of Wildenau (now Nazym, Poland), located a few kilometers southeast of the town of Soldau (Działdowo). The kiln was probably built specifically to produce bricks for the construction of the village church. The external dimensions of the kiln were 7.15 x 6.60 m, the internal ones were 4.55 x 4.20 m. Its walls were made of wild stone and clay, with the kiln partially recessed into a gentle slope. Two arched entrances, 0.9 m wide, led into the kiln, made of brick. The internal walls were also brick. Inside the kiln, there were shelves made of brick, on which the adobe bricks were stacked. Most likely, the kiln did not have a permanent vault. The top of the oven was covered with clay, broken bricks left over from previous firings, and covered with earth [1]. This made it easier to load the bricks into the oven and unload them after firing.

Several layers of fired bricks were found inside the kiln, stacked at different angles on firing shelves. To better distribute the heat inside the kiln, the bricks were stacked loosely and left free space between them.

Another very similar kiln was discovered north of the Polish town of Rippin, in the village of Rypina Privatny. The kiln dates back to the late 13th to mid-14th centuries. Like the previous kiln, it has two entrances and two fireboxes. The walls of the kiln, made of stones, bricks and clay, have survived to a height of 1.2 m. The external dimensions of the walls are 6.5 x 5.4 m, the internal ones are 5.1 x 4.7 m. The thickness of the walls is 0.6-0.7 m. Inside the kiln, along the walls, there are 0.5 m wide shelves for laying green bricks on them, and between the fireboxes there is a third, larger shelf. There was no permanent vault [4].

This type of kiln, with two or three entrances/fireboxes, was probably the most common not only in Prussia but also in Central Europe. Ongoing excavations near Rypin have revealed the remains of two more kilns, similar in shape and size, albeit from a later period.

Probably, the kilns near Rypin were used to produce bricks, which were used to build defensive and religious structures, as well as residential city buildings. The reason for the rather long (several centuries) production of bricks in Rypin in one and the same place could have been the availability of sufficient reserves of high-quality clay.

Brick production requires, in addition to the already mentioned clay reserves and a kiln, also significant spaces for storing the extracted clay, a pit for preparing the plastic mass, a room for molding the bricks, and also for drying the raw bricks, which usually took place under wooden awnings to protect them from the rain. Also necessary are rooms for storing the fired bricks and tools. For obvious reasons, it is almost impossible to find the remains of all this, with the exception of places where clay was previously mined. For example, 30 m down the slope from the kiln in Wildenau there was a round pit filled with water, from which, most likely, clay was once taken, and then water. And the entire space between the kiln and the pit served as a place for the production and storage of raw bricks [1].

As already mentioned, the main tools of a brick maker were a brick mold and a special device for removing excess clay from the mold.

A lump of prepared clay mass was manually placed into a wooden mold (with or without a bottom), sprinkled with clean fine sand from the inside and placed on a special table, and tightly rammed in it to remove voids inside the future brick and along the edges of the mold. After this, the master cut off excess clay, the mold was turned over, the adobe brick was removed from the mold and laid for drying under special awnings to protect from rain. Depending on the weather, drying the adobe could take several days.

An experienced master brickmaker could make 1,200 bricks or even more in a twelve-hour workday [5].

Brick factories

As mentioned above, brick production, for obvious reasons, was not necessarily tied to the construction site. Unlike stonemasons, who worked directly at the construction site, bricklayers were not builders and could be located at a distance from a specific construction site. Cities could have several brick factories [the term “factory” used here, in relation to brick production in the period described, may mislead the reader regarding the scale of the buildings and the volumes of finished products, but it is difficult to find another, more appropriate term. — admin ], differing in the form of ownership — belonging to the order or church authorities, the city, or private individuals.

The establishment of a brick factory initially required the consent of the order, and we have already mentioned the Elbing Dominicans, who received permission from the Hochmeister to produce bricks. In 1378, the Grand Marshal Gottfried von Linden gave the inhabitants of Kneiphof permission to mine clay near the village of Tragheim indefinitely. The townspeople were allowed to build brick kilns according to their needs. Brick production was moved outside the city due to the risk of fires, and also probably because the molding and drying of bricks required significant areas, which, not surprisingly, Kneiphof did not have[2].

The city brickworks were usually under the control of the magistrate, who could

run them himself or lease them to various citizens. Between 1331 and 1337, the

magistrate of Elbing leased the city brickworks to 16 burghers at once.[2]

Often, cities would set up a brickworks for the construction of a specific

church, which would cease operations once the construction was completed. In

1244, the Dominicans in Kulm took a plot of land from the city for 35 years to

set up a brick factory in exchange for another plot of land on which there was a

vegetable garden.

In Rössel (now Reszel), one factory belonged to the city, the other to the church authorities. At the same time, bricks for some constructions were sometimes purchased in neighboring Rastenburg (now Ketrzyn).

In rural areas there was no constant demand for bricks, so their production was

not long-term, but was organized for a short period for the construction of a

specific church, or the bricks were purchased at a nearby castle or city

factory.

In the times of the Order, significant brick production facilities existed only

near castles during their construction. This is especially true for remote

castles, for the construction of which it was impossible to purchase bricks in

the area or deliver them from existing factories without significant

transportation costs. Any surplus bricks, if any, were produced at castle

factories, were sold on the side.

The volume of brick production in the 14th-15th centuries fluctuated between 16 and 75 thousand pieces per year, averaging 20-40 thousand pieces. The stocks of bricks that were kept in castles at that time are impressive: for example, 720 thousand bricks were stored in Thorn Castle in 1384 [2]. Such stocks were probably kept as a reserve in case of military action, when they could be used for the rapid reconstruction of defensive structures or their restoration.

As for the cost of bricks, according to the records from the Marienburg Book of the Chief Treasurer (1399-1409), in 1404 the construction of a brick factory and the production of 200 thousand bricks in the Ragnit Castle (now Neman) cost the Order 101 marks. At the same time, the cost of 1000 bricks was 11 scots*. Roof tiles were significantly more expensive - 20 scots for 1000 pieces.

Brick sizes

For several centuries, there were no quality standards or specific sizes for bricks. The quality of the brick was determined by the master brickmaker himself. The size of the brick often depended on the size of the mold made by the master for its molding (in the early stages of brick production, this was often a tradition of the places where the masters came from) and the degree of shrinkage of the clay during firing. In fact, the same brickmaker, using the same frame for molding the adobe, could get bricks of different sizes depending on the quality of the clay and the firing process.

For the Order times (i.e. from the second half of the 13th century to the beginning of the 16th century), we can talk about the sizes of bricks that fit into the range of 24-34.5 cm in length, 12-18 cm in width, and 6.5-10.5 cm in height. At the same time, extreme sizes were rare. During the heyday of Order construction (1330-1410), some relative standardization of bricks occurred and the most common sizes were 29-31 by 13.5-15 and by 7.5-9 cm [2] (residents of the Kaliningrad region call these large bricks of the Order times, which differ visually from the smaller German bricks of the 19th-20th centuries, "lapti"). For example, the size of the bricks of the Allenstein Castle (Olsztyn) is 30 x 15 x 8 cm. And the size of the brick of the Church of St. Andrew the First-Called (late 14th century) at the former Franciscan monastery in Wartenburg (Barczewo) is 30 x 15 x 10 cm [6]. It should be noted that as the scale of brick construction expanded in the world, proportions were empirically determined in which the width of a brick was approximately equal to its double height, and the length to double the width (i.e. 1: 2: 4). Such proportions best suited the convenience of bonding the brickwork and its strength and have been preserved to this day [5]. The so-called "imperial standard" appeared in Germany only in 1872 (now it is called the "old imperial standard", since a new standard for brick sizes was introduced in Germany in 1950). According to it, only bricks with dimensions of 25 x 12 x 6.5 cm were allowed to be used for state buildings.

Very often, even at one site, bricks of different sizes were used, which may indicate, among other things, that the bricks for the construction site were supplied by different manufacturers, and that different bricklayers worked at the site, who could also come from different places.

Notes:

* Scot (shkot) is a monetary unit equal to 1/24 mark.

Sources:

1. Wasik B. Riddles from the mystery of the middle-aged Prussians . — Archaeology of Historic Poland, vol. 25, 2017.

2. Herrmann C. Middle Eastern Architecture in Preussenland. Studies on the history of art and geography. — Petersberg, 2007.

3. Gasewind G. The relations between the landowners in East Germany . — Emsdetten, 1938.

4. Lewandowska J. Cemeteries in Old Rypinia . — Archaeology of Historic Poland, vol. 25, 2017.

5. Rupp E., Friedrich G. The evolution of the Ziegelherstellung . — Kingswinter, 1993.

6. Museum of Modern Art, No. 38, Olsztyn, 2019.