Windmills of the Order Prussia

One of the important changes that occurred in the Middle Ages in the organization and functioning of village communities, as well as in urban crafts, was the popularization of water machines. This primarily included the water mill, used not only for grinding grain and malt, raw materials necessary for the preparation of basic products such as bread and beer, but also for driving such machines as sawmills, grinding mills, forges, and fulling mills. The devices themselves, driven by water, were known since ancient times, but their widespread use began in the Middle Ages.

There was also a development in the medieval use of windmills powered by wind energy, which was also known before. Although their function was only a supplement to the existing network of watermills, in regions where local conditions made the use of water power difficult or impossible. This was also present in the late Middle Ages, during the reign of the Teutonic Order in Prussia. We will try to identify the characteristic elements of the local character of this phenomenon, the legal and economic framework in which the owners and users of windmills operated. Unfortunately, due to the state of preservation and the nature of the sources at our disposal, this description will probably be far from complete.

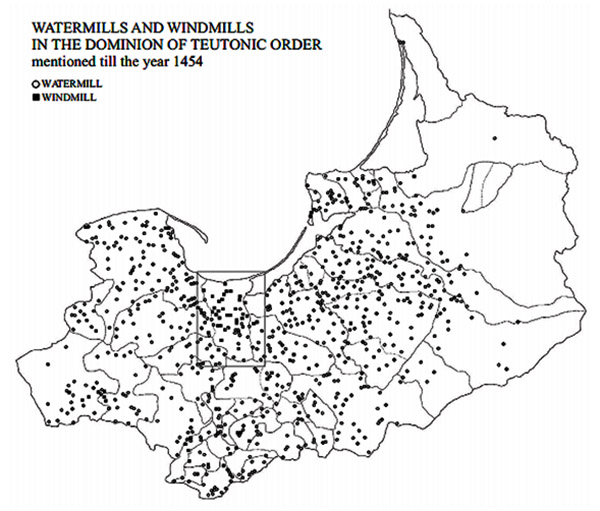

Location of windmills in the Teutonic Order's possessions in Prussia

By way of introduction, it is necessary to note the special circumstances of the development of mills in the state of the Teutonic Order in Prussia. The Order, in exercising its right to water, compulsorily introduced a legal situation in which its consent was always required for the construction of watermills. These rules also applied to the construction and use of windmills. In practice, this right was exercised both by the Teutonic Order itself and by the Prussian bishops who had authority in their territory (the bishoprics of Culm, Pomesan, Ermland and Samland), as well as by the cathedral chapters. A windmill could only be built with their permission, with an indication not only of the annual fee for it to the competent officials representing the authority of the Order, the bishop or the chapter, but also of its exact location. These provisions, as well as a number of others, were recorded in the mill privileges issued to certify the right, or in the contracts for the sale and purchase of the windmill. Of course, the decision to build windmills, as in the case of watermills, was strictly linked to the circumstances of the settlement, and therefore to the existence of real needs that ensured the economic profitability of such an undertaking. The choice of a windmill instead of a watermill was usually determined by local hydrological conditions that prevented the practical use of water energy.

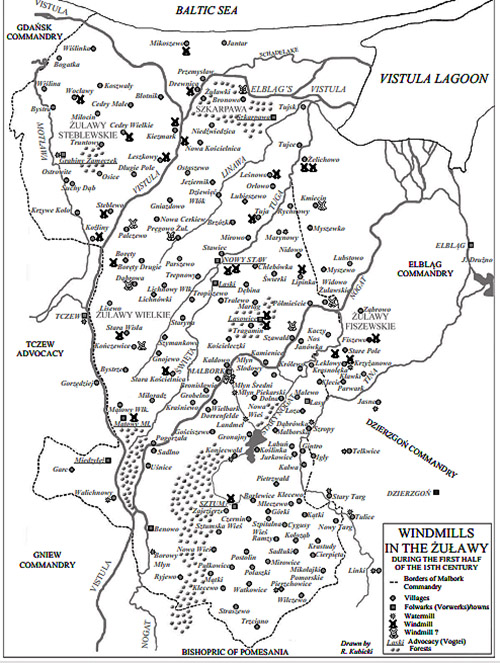

The first mention of a windmill in the Prussian possessions of the Teutonic Order dates back to the end of the 13th century. In 1299, Bishop Siegfried of Samland issued a founding document for a settlement near his castle Schönewik (Fischhausen/Primorsk), which mentions the right to build a windmill (Urkundenbuch des Bisthums Samland, P.98). Another mention of a windmill from this area dates back to 1337. It was then that Bishop Johann of Samland gave a miller named Heinrich a windmill located on a hill near the town of Schönewik/Fischhausen. (UBS, P. 222–223) Later, windmills were built in various parts of the Order’s possessions, but they were the basis for the grain processing industry only in the area called Żuławy (Werder), which covered the deltas of the Vistula and Nogat, and was part of the Marienburg Commandery. While in the Schlochau (Czluchow) Commandery and the Kulm Land there were significantly fewer windmills.

In the case of Żuławy, the main reason for building windmills was the local hydrological conditions, which were unsuitable for building watermills. While in other regions, windmills served as a supplement to the capacity of existing watermills, and were also built in cases where building new watermills would have been unprofitable. Due to the cost of building a watermill, its future profitability may be lower than that of a windmill, especially if local grain production does not require the use of equipment with a high milling capacity. At the same time, it should be emphasized that most charters for the construction of windmills and, in general, information about such mills in operation date back to the second half of the 14th and the beginning of the 15th century, a period when a network of watermills in the Prussian Order had already been formed. Of the total number of mills in the Prussian Order lands, windmills accounted for only 7%, and, as already mentioned, they were only an additional element of the watermill network. It should also be remembered that the number of surviving references to windmills that existed at that time was probably smaller than that to watermills, which were much more durable structures, rebuilt in the same place over hundreds of years. In total, the ratio of windmill to watermill must have been at least 1 to 12, and given their processing capabilities, the advantage of watermills was even greater. For all these reasons, with the exception of Żuławy, windmills were seen only as a supplement to networks of watermills built and operated as stationary machines.

Rules for the construction and use of windmills

Unfortunately, the surviving sources do not allow for an accurate reconstruction of the windmill production process. This also applies to the Żuławy region, which is of particular interest. The first mentions of organised milling in this area appeared with the large-scale settlement in the first half of the 14th century. It is known that when settling new lands, the Order used a system of reserving suitable sites for mills, indicating this in separate clauses in the charters-privileges issued when creating new settlements. They guaranteed that the exclusive right to build a mill within a specific settlement would belong to the Order. In later times, however, no watermills were built in these places, only windmills. Similarly, as in the case of the construction of watermills, the issue of decisive importance for their efficient operation was the choice of a suitable site. It was important to find a place with the best conditions for the wind (potential wind energy). Research by Wolfgang La Baum has shown that from ancient times settlements in the Vistula Valley were concentrated only in relatively dry areas lying above the water level. After the Teutonic Order completed the reclamation of this area, these became natural hills that could be used as sites for building windmills. Sources dating from the early 15th century mention windmills on most of these hills, as they were the only ones in the region suitable for their construction (such hills were near Tragheim (Tragamin), Pruppendorf (Kraszewo), Gnojau (Gnojewo), Gross Lassowitz (Lasowice Wielkie), Lindenau (Lipinki), Klein Mausdorf (Myszewko), Jonasdorf (Janówki) and Schöneberg (Ostaszewo); windmills are not mentioned only in the vicinity of Myszewko and Ostaszewo).

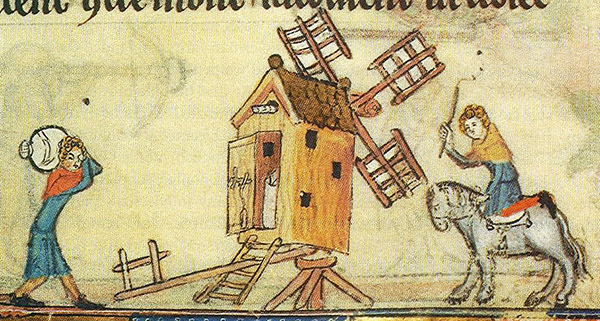

In this regard, grain windmills were built in Żuławy in places that had already been explored and used earlier, especially if there was a suitable elevation for their construction. There is no information about the types of windmills that existed at that time. They were probably tent and pillar (gantry) mills.

The oldest pictorial source and evidence of windmills in Żuławy is a painting in Artushof in Danzig depicting the siege of Marienburg, painted around 1480. The work shows three windmills, two of which (probably of the tent type) were located near Dirschau (Tczew) and Neuteich (Novy Staw).

Basic information about the legal circumstances of the operation of windmills, and even some design details of these buildings, can be obtained from the content of the privileges for milling, issued in connection with the conclusion of a contract between a representative of the authorities and an entrepreneur building a new or operating an existing mill. The most important issue was to establish the term and amount of annual payments and other obligations that had to be fulfilled by the lessee. The rent was set in the form of grain or money. The windmill had to pay a quitrent annually to the representative of the local authority (the commander or bailiff, bishop or chapter). Such grain was taken in the form of mill dues, which were collected from persons grinding grain for their own needs. According to the mill law of the Teutonic State, for each ground sheffel of grain, a miller working in a water or wind mill took one “measure” (Latin: mensura, German: Metze), which was equal to 1/16 of a sheffel (1 sheffel = about 55 liters), i.e. about 3.4 liters [1].

Most often, the rent for grain was 3-4 lasts per year (1 last = 3,300 liters), which was equal to 180-240 sheffels (9,900-13,200 liters of grain). Under special circumstances, both a lower rent (2 lasts per year) and a higher rent of up to 7 lasts were charged. Sometimes the rent consisted not only of grain, but also of a certain amount of money. Of course, the specified rent amount (3-4 lasts of millet, or rye, or barley per year) had to correspond to the actual milling capacity of the windmills. While the average rent from one mill, expressed in money, was 4 Prussian marks (one Prussian mark = about 180 grams of silver).

| No. | Rent amount | Number of mills paying rent | Location of the mills | Note |

| 1 | 2 grain flippers | 1 | Kielp/Kiełp | |

| 2 | 3 grain fins | 7 | Neudorf/Nowa Wieś, Rehden/Radzyń Chełmiński, Unislaw/Unisław, Neuenburg/Now nad Wisłą, Subkau/Subkowy, Putzig/Puck, Königsdorf/Królewo | Puck - 2.5 tbsp of rye and 0.5 tbsp of wheat |

| 3 | 3.3 rye fins | 3 | Lesewitz/Lasowice | 10 rye lasts in total from three mills |

| 4 | 3.5 rye fins | 1 | Ksionsken (Hohenkirch)/Książki | |

| 5 | 4 grains (rye) | 3 | Weinsdorf/Dobrzyki, Rehden/Radzyń Chełmiński, Lewen/Mlewo | |

| 6 | 4.5 fins | 1 | Culmsee/Chełmża | 1.5 lasta - rent for 1/3 of the mill |

| 7 | 5 fins | 1 | Putzig/Puck | 4.5 tbsp rye and 0.5 tbsp wheat |

| 8 | 7 fins | 1 | Saalfeld/Zalewo | 3.5 tbsp of grain and 3.5 tbsp of malt |

It is noteworthy that in the case of windmills, rent in grain was the dominant payment method. Of the nearly forty windmills with known types of rent, 22 mills paid rent in grain and only 12 in cash. However, references to rent from windmills mainly date back to the period when rent in grain was becoming increasingly common for watermills as well. The documents confirming the right to build and operate a mill also indicate the deadline for paying the rent due from the owners and lessees of the windmills. In the case of windmills, a solution was often used that provided for dividing the payments into four parts. In addition to the rent, the administrator of the windmill was sometimes obliged to provide the authorities with the mill free of charge. This was the case, for example, with the windmill near Culmsee (Chelmza), where in 1381 the chapter sold part of the windmill to Johann Kromer and imposed on him the obligation to grind for the chapter free of charge. ( Urkundenbuch des Bisthums Culm, P.283 ) Likewise, the windmill in Gross Morin (Muzinno , 1404) was to grind free of charge for the court of the commandery of Nessau (Nieszawa), and two mills in Rehden (Radzyń-Chelmiński, 1449) for the local commander. It is also known that in such a case the commander had to send his assistants to the windmills. ( GStA PK, XX. HA, OF 97, f. 209v ) In addition to additional obligations of this kind, the owner of a windmill could also receive special support in the form of an order for specific villages to grind grain in his windmill. Such decisions, although rare, were applied both by the Order (Nickelswalde/Mikoszewo 1437 - a mill for the villages of Mikoszewo , Prinzlaw (Przemysław) and Pasewark (Jantar) - GStA PK, OF 97, f. 50v ) and by the bishops (Wolfsdorf/Wilczkowo 1379 - an obligatory mill for the inhabitants of the villages of Wilczkowo , Warlak (Vorławki) and Petersdorf (Piotrowo) - Codex diplomaticus Warmiensis oder Regesten und Urkunden zur Geschichte Ermlands, P.47; Wuzlak/Wozlawki 1380 - a mill for the villages of Wozlawki and Trautenau (Trutnowo) - Ibid, P.79).

The windmill owner's property was not limited to the mill. Sometimes he had his own vegetable gardens, used pastures belonging to the commander or a nearby village.

Thus, according to the deed of sale of the windmill in Lichnowy in 1420, the miller was also granted the right to a vegetable garden. ( Handfesten der Komturei Schlochau, P. 179-180 )

According to the privilege of the town of Rehden for 2 mills, one opposite the castle, the second outside the town, the miller had the right to pasture 2 horses, 12 heads of cattle and 20 pigs on the meadows belonging to the commandery. ( GStA PK, OF 97, f. 209v )

In a privilege of 1406, the owner of the windmill in Gallgarben (Marshal) was granted the right to use the pastures on an equal basis with the villagers, and he was also obliged to pay the shepherds. ( GStA PK, XX. HA, Ostfoliant, No. 129, f. 229r )

Often the miller had the right to cut wood from forests belonging to the Teutonic Order or the bishop's chapter for fuel, as well as construction timber used for repairing the windmill. For this reason, various types of wood used for the production of drive shafts, brake wheels, construction timber for sails and roofing were mentioned (Rychnau/Rychnowy 1379 — HKS, pp. 137–138 , Lichtenau/Lichnowy 1420 — HKS, pp. 179–180 , Mikoszewo 1437 — GStA PK, OF 97, f. 50v–51r , Gross Lassowitz/Lasowice Wielkie 1440 — GStA PK, OF 97, f. 73v , Radzyń Chełmiński 1449 — GStA PK, OF 97, f. 209v , Saalfeld/Zalewo 1451 — GStA PK, OF 100, f. 4r , Weinsdorf/Dobrzyki 1461 - GStA PK, OF 100, f. 4v ). In many cases, there were also special rules for obtaining and financing the purchase of iron parts used in the construction of windmills. In the case of a windmill located near Chełmża, it was decided in 1381 that the miller should himself purchase the so-called "small iron parts" and pay for a third of the supply of "large iron parts". ( UBC, P.283 )

Furthermore, in the case of the windmill in Zalewo, the Teutonic Order in a document from 1451 decreed that the miller had to purchase the necessary iron parts for the mill himself. ( GStA PK, OF 100, f. 4r )

A similar provision was in the document on privileges for the mill in Dobrzyki from 1461, where the miller had to search for large and small iron parts himself. ( GStA PK, OF 100, f. 4v )

A number of regulations also dealt with the issue of obtaining millstones. The purchaser of two windmills in Łasowice Wielkie in 1440 and the millers operating the windmills in Mikoszewo (1437 — GStA PK, OF 97, f. 50v ) and Reimerswalde/Lesznowo (1441 — GStA PK, OF 97, f. 92v) had to purchase the millstones themselves. It is also clear from the surviving account books that the millstones intended for windmills were treated as a separate category of expenses. The millstones were sold by representatives of the Teutonic Order, who acted as sales representatives of the millers. The size and quality of the millstones could vary, as can be assumed from the price, which varied from 3 to 12 marks. It is unclear what caused such a wide range of prices. In addition to size and quality, there may have been special rules for the millstones, according to which the Teutonic Order was obliged to contribute to some of the costs of maintaining the selected windmills. Surviving account books mention that in the case of several windmills (Montau/Montowy , Petershagen/Želichowo, Subkau/Subkovy and Rosenberg/Ruziny) they changed owners between 1404 and 1417, i.e. for more than ten years. Unfortunately, it cannot be said with certainty that one millstone was used for such a long time. This can, however, be assumed from the profitability. The purchase of a millstone had to be financed from the income received from the windmill; for example, the payment for the millstone in Želichowo must indeed have taken up to 10 years. The mill paid a rent of 4 marks annually, so it had to earn an income that would cover the wages of the miller and staff, the necessary repairs and the purchase of a millstone. It is particularly important that the purchase price of the millstones was the same in the cases given, and it increased from 6 marks in 1404 to 10 marks in 1417 only in the case where the miller worked at the mill near the Order granary in Montowy.

Furthermore, surviving accounts show that in 1396 the commander of Marienburg spent as much as 36 marks on a single pair of millstones, which would have been an incredibly high price. ( Die Reste des Marienburger Konventsbuches, P.70 ) But this may simply be an error in the source.

In documents regulating the relations of millers with higher authorities (the Teutonic Order, the bishop), facts of assistance to the miller in the event of unforeseen incidents and natural disasters were sometimes also indicated. In the privilege for a windmill near Fischhausen from 1337, the Bishop of Samland guaranteed the supply of wood to the miller for the repair or restoration of the windmill as a result of regular wear and tear, as well as due to gusts of wind or other accidental events. However, he had to finance all repair and restoration work himself. ( UBS, P.223 ) <On the seventh calends of July in the year of our Lord 1337, the Bishop of Samland Johann von Clare granted the miller Heinrich a windmill in Fischhausen as a hereditary right. The cost of the mill including equipment was 40 marks. On St. Martin's Day, the miller had to pay a tax of 3 marks to the bishopric. Also in Samland, windmills existed in the area of Schaaken (1392) and Lochstedt (1423 - GStA PK, Ordensbriefarchiv , Nr. 4216 - translator's note > .

Moreover, in the document on the operating conditions of two windmills near Rehden from 1449 it was stated that in the event of their destruction during a war or as a result of a fire that would lead to the destruction of the mechanisms and the millstone, the Rehden commander was to provide assistance and cover half the costs of restoring the windmill, and in the event of its destruction by a storm or strong wind he was to cover only half the costs of its reconstruction, not counting, however, the costs of restoring the mechanism and the millstone. ( GStA PK, OF 97, f. 209v )

Information on the cost of erecting and maintaining a windmill is incomplete. In 1337, the Bishop of Samland spent 40 Prussian marks on the construction of the already mentioned windmill in front of Fischhausen. Later, these costs were probably higher, although inflation and the cost of the so-called small marks (1 good mark = 2 small marks) for the 15th century must be taken into account. In any case, the city windmill built in Kulm in 1443 cost a total of 222.5 marks. ( GStA PK, OF 83, p. 96 )

On the other hand, the commander of Thorn, reporting to the Grand Master in 1453 on the costs of maintaining and developing the production equipment under his direction, mentioned the construction of a new windmill at the order estate in Kovrosh/Kovruzh, the cost of which amounted to 150 marks. ( GStA PK, OBA, Nr. 12058 )

The prices of these objects also indirectly show the approximate cost of building a windmill. For example, in 1406 a certain Nikolaus bought a windmill in Leklau/Leklowy for 110 marks, paid in several payments of 15 marks, the first on St. James's Day that year, and the rest in the following years, until the final payment of 20 marks. ( Das Pfennigsschuldbuch der Komturei Christburg, P.92 )

The windmill in Lichnowy was sold in 1420 for 50 marks. In 1440, a miller named Jörge bought 2 windmills and 12 morgen (approx. 6.7 ha) of land in Gross Lassowitz (Lasowice Wielki) from a Teutonic pfleger for the symbolic price of 5 marks, payable in annual installments, except for the rent, of one mark for five years. This may have been due to the fact that the equipment needed expensive repairs.

In addition to local conditions, the decision to build a windmill may also be based on legal considerations. The Teutonic Order was very strict about ensuring that all city mills were under its exclusive control, allowing city authorities to own their own milling equipment only in exceptional cases. For this reason, even the right to build windmills in an urban area should be considered a privilege. Such privileges were granted in 1377 to the city authorities of Konitz (Chojnice), who were allowed to build two windmills for their own needs. ( HKS, P.132 )

They took advantage of this right, as is shown by the fact that in 1420 the Konitz town council granted private individuals a windmill located opposite the village of Lichnowy, retaining control over it in case the new owners wanted to resell it. Similar provisions ensuring control of the windmill were also applied by the Order when in 1441 it issued a document concerning the windmill in Lesznowo. ( GStA PK, OF 97, f. 92v )

To sum up the above observations, it can be noted that windmills ultimately played a complementary role to watermills in the lands of the Teutonic Order in Prussia. An exception to this rule was the situation in Żuławy, due to local water conditions, which, with some exceptions, prevented the use of watermills. Strict control of the right to build and operate windmills, as in the case of watermills, was intended to ensure their optimal use. State control over production indirectly guaranteed its profitability. On the other hand, the varying amounts of rent were linked above all to the estimated value of the grain and malt milled annually. In addition, the owners and millers working in windmills could count on additional support in the form of free construction timber needed for the maintenance and repair of their mills. The authorities also provided agency services for the purchase of millstones. In the second half of the 15th century. The situation did not change significantly, although in the Kulm region after the Thirteen Years' War some watermills were not rebuilt but replaced by windmills operated by private owners for their own needs. At that time, the use of windmills for drainage works in the Żuławy area was not yet known. However, later it became possible and continued until the 20th century, becoming a hallmark of the local landscape.

Notes:

1. The above-mentioned milling regulations were issued around 1335-1341 by Grand Master Dietrich von Altenburg. In addition, it was stipulated that in the case of milling with the help of a miller's apprentice, an additional fee of 1 pfennig had to be paid for grinding 2 sheffels of grain and grinding 6 sheffels of malt. In addition, if anyone wanted to grind on their own, they could not be forced to take a miller's apprentice with them.

Application

List of windmills in Knights' Prussia, with dates of foundation/first mention.

– Balga Commandery: Głębock/Tiefensee (1437)

– Birgelau Commandery: Bierzgłowo/Birgelau (15th c.)

– Bishopric of Kulm: two mills in Wąbrzeźno/Briesen (1414)

– Chapter of Culmsee: Chełmża/Culmsee (1381)

– Schlochau Commandry: two mills in Chojnice/Konitz (1377), Człuchów/Schlochau (15th c.), Pawłówko/Pagelkau (1425) Rychnowy/Richnau (1379) – Dzierzgoń/Christburg Commandry: Dobrzyki/Weinsdorf (1437, 1461), Krzyżanowo/Notzendorf (1407), Stary Dzierzgoń/Alt Christburg (1383), Zalewo/Saalfeld (1451)

– Elbing Commandery: Fiszewo/Fischau (1402), Kmiecin/Fürstenau (1406), Królewo (1426), Nowa Wieś/Neuendorf (1402), Wilczęta/Deutschendorf (1469)

– Commandery of Danzig: Łeba/Lebe (c. 1400), two mills in Puck/Putzig (c. 15th century)

– Commandery of Königsberg: Lochstedt (1423), Marshal's/Gallgarben (1406), Roadside/Kirschappen (1398)

– Marienburg Commandery: Boręty/Barendt (1453), Bronowo/Brunau (1404), Cedry Wielkie/Groß Zünder (after 1410), Dąbrowa/Damerau (1404), Drewnica/Schönbaum (1400), Falkenberg, Kiezmark/Käsemark (1427), Kończewice/Kunzendorf (1402), Koźliny/Güttland (after 1410), two mills in Lasowice Wielkie/Groß Lesewitz (1407, 1440), Leklowy/Lecklau (1391), Leszkowy/Letzkau (after 1410), Leśnowo/Reimerswalde (1441), Lipinka/Lindenau (1396), Mątowy/Klein Montau (1404), Mikoszewo/Nickelswalde (1400), Nowa Kościelnica/Neu Münsterberg (1417), two mills in Nowy Staw/Neuteich (1402, 1440), Palczewo/Palschau (1399), Pręgowo Żuławskie/Prangenau (1408), Stara Kościelnica/Alt Münsterberg (1396), Stara Wisła/ Alt Weichsel (1450), Steblewo/Stüblau (1400), Subkowy/Subkau (1402–1409) Szawałd/ Schadwalde (1401), Sztum/Stuhm (1447), Tuja/Tiege (1404), Widowo Żuławskie/Wiedau (1401), Wocławy/Wotzlaff (after 1410), Żelichowo/Petershagen (1400)

– Commandery of Nessau: Murzynno/Groß Morin (1404)

– Commandery of Brandenburg: Ushakovo/Brandenburg (1425), Vesyoloye/Brandenburg Unterflecken (1447)

– Chapter of Pomesania: Łęgowo/Langenau (1377), Nipkowo/Gross Nipkau (1399), Różnowo/Rosenau (1394)

– Rehden Commandery: two mills in Radzyń Chełmiński/Rehden (1449)

- Commandery of Ragnit: Polesk/Labiau (1430)

– Roggenhausen vogtstvo: Książki/Groß Ksionsken (1425), Trzciano/Trzianno (1419), Wielkie Zajączkowo/Groß Sanskau (1447)

– Samland chapter: Primorsk/Fischhausen (1337)

– Althaus Commandery: Chełmno/Culm (1443), Kiełp/Kielp (1438), Starogród/Althaus (1442)

– the mayoralty of Dirschau: Miłobądz/Mühlbanz (1402–1409), Nowe nad Wisłą/Neuenburg (1437), Różyny/Rosenberg (1404), Subkowy/Subkau (1402–1409)

– Commandery of Thorn: Kowróz/Kowros (1453), Mlewo (1407), Świętosław (1418), Unisław/Wenzlau (1384)

– Tuchel Commandery: first mill in Lichnowy/Lichnau (1405), second or the same mill in Lichnowy/Lichnau (1420)

– Bishopric of Ermland: Wilczkowo/Wolfsdorf (1379), Wozławki/Wuslack (1380).

Sources and literature:

GStA PK, XX. HA, OBA

GStA PK, XX.HA, OF

Urkundenbuch des Bisthums Culm , ed. C. P. Woelky, vol. 1–2. Danzig, 1885–1887.

Urkundenbuch des Bisthums Samland , ed. C. P. Woelky, H. Mendthal. Leipzig, 1891–1905.

Bertram H., Kloeppel O., LaBaume W. The Weichsel-Nogat-Delta: Analysis of the social development of individual landowners, their subsequent use and their subsequent use in houses and farms . Danzig, 1924. — http://prussia.online/books/das-weichsel-nogat-delta

The collection book of the Christburg books , hg. u. bearb. v. H. Wunder, Cologne–Berlin, 1969.

Handbook of the History of the City (Quells and Answers to the Questions of the West, vol. X), ed. P. Panske. Danzig, 1921.

Kubicki R. Two years ago, the law of the 13th-15th centuries was passed in Prusach. (before 1454 r.) . Gdańsk, 2012.

Schmid B. The art and culture of the Western Provinces, vol. 4: Marienburg (the New York State Forest and the Great Wall and the local communities) . Danzig, 1919.