Wells in the castles of the German Order

We will not waste the reader's time by presenting the hackneyed truth that "without water you can't go anywhere". We will only mention that water is important for humans in several ways. In addition to the fact that we need water for drinking, it is also used for various household needs, from its use by humans for hygiene procedures to its use in agriculture or construction.

In 2018, a Neolithic well was discovered during the construction of a motorway in the Czech Republic. Archaeologists, having conducted a dendrochronological analysis of the oak logs of the well frame, established that it was built more than 7,200 years ago. Thus, this square well frame measuring 0.8 x 0.8 m and 1.4 m high is one of the oldest surviving wooden structures on Earth [1].

In this article we will talk about drinking wells of not so respectable age. We will talk about wells that existed in the territory of East Prussia since the Middle Ages.

First, let's define some terms and typology of wells.

In general, a drinking well consists of a well shaft (or well pit) and a lifting mechanism, with the help of which water is raised to the surface. As such a mechanism, either a rocker (the so-called "crane"), located at some distance from the well, or a winch, which is installed directly above the well shaft, is used. A rope or chain is attached to one end of the crane or winch. A bucket is attached to the opposite end, into which water is collected. The well itself, to protect it from dirt and debris (leaves, branches, dust, animals, etc.), is usually covered with a canopy or a kind of box with a door is built above it. Filter material in the form of crushed stone, small stones and sand is poured onto the bottom of the well.

There are two ways to dig a well, which differ depending on the type of soil: open and closed. The first method is used when there is solid soil and free space that allows you to dig a hole significantly larger than the size of the future well shaft. The hole is deepened to the aquifer, and then a frame is built inside it. The space between the walls of the frame and the edges of the hole is filled with the soil selected earlier.

The closed method is used when there is loose soil or insufficient space to dig a large hole. In this case, the walls of the well shaft are lined with protective material as the shaft deepens, gradually lowering the lower layers of casing and building them up from above.

Wells also differ in the shape of the log house (round and rectangular) and the material from which the log house is made (wood, stone, brick).

Wells dug in the territory of East Prussia can be divided into castle, manor, city and village wells.

We have no information about the wells that the Prussians used before the conquest of their lands by the German Order. Therefore, the oldest wells that have come down to us date back to the Order's times.

There is no doubt that the knights, finding themselves in the territory bordering the hostile Prussian tribes, understood the importance of not only reliable castle walls protecting them from enemy attacks, but also water sources inside them. Despite the fact that the order built castles near natural or man-made water sources (rivers, streams, lakes, ponds), a well was dug in any castle without fail, and in large fortifications there were several. It is the castle wells that will be discussed in this article.

The location of the well within the castle walls was determined by its special importance for the defensive and economic functions of the castle, especially in armed conflicts, when the castle became the object of a long siege, and access to drinking water guaranteed the survival of the garrison and the preservation of its defensive capability.

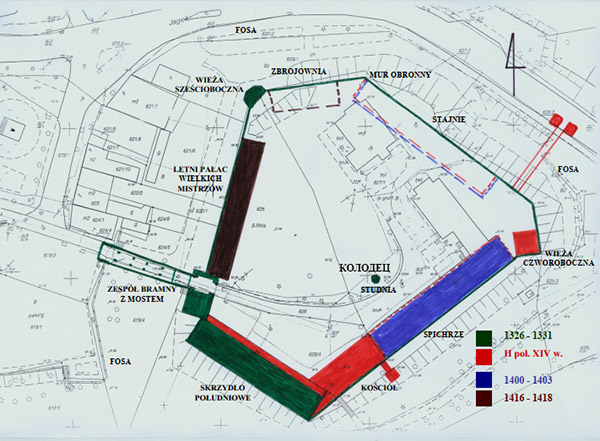

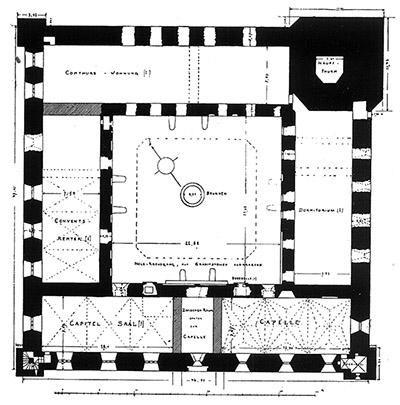

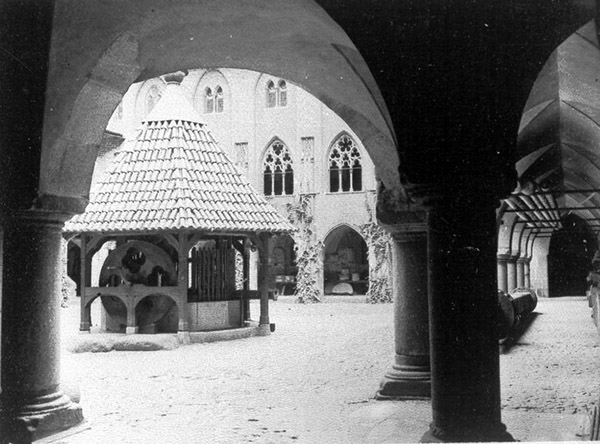

Wells built in small castles were usually located in the center of the castle courtyard, which provided approximately equal access to a water source from any point of the fortification, which was especially important when extinguishing a fire.

The correct placement of wells also facilitated the economic work in the castle, so they were often built near such rooms as the kitchen, brewery, bakery and malthouse. This was practiced in the case of large castle complexes with spacious courtyards, where the economic rooms were located in a separate wing. Wells could even be located inside the castle premises.

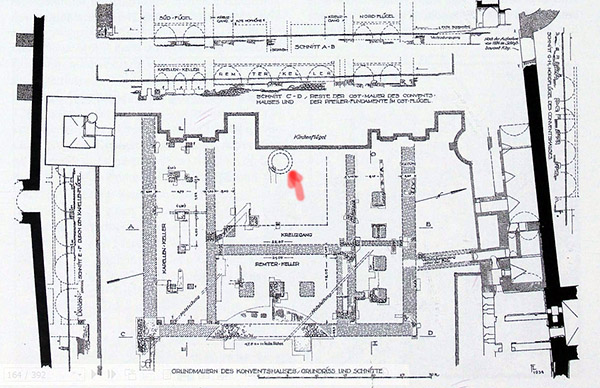

There were at least 19 wells in Marienburg Castle [2], most of which were located right next to the utility rooms. The presence of a kitchen in both the High and Middle Castles required the construction of separate wells nearby. A well has survived to this day in the window niche of the High Hall of the castle, adjacent to the Great Refectory, where the brethren ate, and in the kitchen, where food was prepared. On the castle's foreburg, wells were located next to the cattle yard, near the cooperage, the malthouse, in the brewery, in the garden, near the stables, etc.

In the Graudenz (Grudziadz) castle, which had a fairly large courtyard, the well was located near the kitchen, bakery, brewery and other outbuildings.

In the smaller Strasburg (Brodnica) castle, a well was also built near the kitchen.

The well in Thorn Castle (Torun) was located in the main southern wing, the first floor of which was occupied by outbuildings and where the kitchen was located.

Near the kitchen there were also wells in the castles of Sztum, Preussisch Mark (Przezmark) and Bütow (Bytów).

In the Königsberg castle, the main well was located in the center of the castle courtyard [4]. At least one more was in the garden, and the water from it was also intended for the bathing room added to the Grand Master's residence at the end of the 15th century. The main well served its purpose until the end of the 1920s.

The well was also used to satisfy the hygienic needs of the castle inhabitants and its garrison (washing and laundry). In Marienburg, on the first floor of the castle, on the porch in front of the refectory, there was an opening through which water was taken from a well, probably located in the basement. On the floor where the water was supplied in this way, there was a toilet (lawater). In Das Ausgabebuch des Marienburger Hauskomturs, i.e. in the treasury book of the commander of Marienburg, the existence of a well near the bathhouse at the local infirmary is mentioned.

Well water was also used for washing in the Ragnit (Neman) castle [5], but the reason for this was, first of all, its poor quality, which will be discussed below.

All wells in Teutonic castles known from historical and archaeological sources were partially or completely lined with stone. The lining is a dense casing along the entire height of the shaft - from the bottom to the head. The main task of the lining is to protect the well shaft from crumbling and to protect it from contamination.

Stones bound with lime mortar were most often used for cladding. For example, the cladding of the well of the Mewe (Wrath) castle and the High Castle in Marienburg was made of granite. The well in the Ragnit castle was lined with limestone.

Sometimes the stones used for the lining were processed. The well in Bütow Castle, mentioned above, was made of completely processed stone above the ground. The three tiers of lining below the ground were made of stone processed on one side, with the processed side of the stones facing the inside of the shaft. Even lower, the shaft was lined with unprocessed stone. The well in Osterode Castle (Ostróda) was lined with stone, also processed on only one side [2].

In addition to stone, wood was also used to line castle wells. The well shaft in Strasburg is lined with stone from the surface to a depth of approximately 8 m, and below it is a wooden frame.

The same combination of materials was used for the lining of one of the wells in the High Castle in Marienburg (the upper part of the well shaft was lined with stone, while oak was used for the lining below), as well as in the castles of Herrengrebin (Grabiny-Zameczek) and Roggenhausen (Rogórzno-Zameczek).

Another example of combining materials for lining is the well in the castle of Soldau (Działdowo), where the lower part of the shaft is lined with brick, and the upper part with wild stone. Also, a combination of stone and brick was used for lining the well shaft in Königsberg [4].

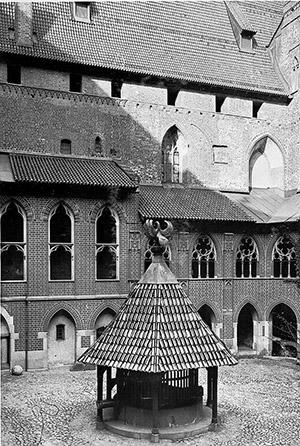

The part of the well frame located above the ground, in addition to the construction of walls protecting the well from debris and dirt getting into the water, was additionally covered with a canopy or roof. Being an insignificant architectural detail, such structures were very rarely recorded in historical documents and were least preserved from an archaeological point of view. The scant information that we have indicates that logs were used as a support for the roof, and tiles (Stum), lead (Herrengreben) and wood (Marienburg) served as roofing material [2].

In Strasbourg, Soldau and Osterode, wells were located in galleries located along the perimeter of the courtyard, which eliminated the need to build a separate roof over the well.

As is known, a significant part of the Order's lands were located in lowlands with small absolute heights above sea level. And the knights often chose places for building castles that were not the most optimal from a hydrographic point of view - in swamps, low capes. Often, nearby watercourses were dammed in order to install a water mill on them and, at the same time, to create a pond that served as a natural barrier for the enemy. All of the above factors determined the relatively shallow occurrence of aquifers in such areas, and, as a consequence, the small depths of drinking wells. Therefore, the water in them, already stagnant, was not of the best quality. The already mentioned lining of the well shaft protected it from the ingress of polluted surface water from the outside, which is why it was important to maintain the tightness of the well walls. (In parentheses, one can note a highly controversial statement found in one of the sources that the inner courtyard of the order's castle had a special slope towards the well to drain rainwater [5]). In addition, as already mentioned above, the builders placed various natural filters at the bottom of the well. In some cases (Mewe, Marienburg, Strassburg), the bottom of the well was covered with a wooden flooring, which may also have played the role of a kind of protective membrane [2].

An important part of the well design was the lifting mechanism, which facilitated the raising of water to the surface. The most common was a well winch, consisting of a shaft on which a rope or chain was wound and one or more wheels designed to rotate the shaft. The shafts could be bound with iron and secured with metal hoops for strength. Until the end of World War II, there were structures with a turning wheel, erected over wells in the castles of Königsberg and Marienburg. Water from the castle well in Königsberg was raised to the surface using a pump until the spring of 1945 [7].

The treasury book of the Komtur of Marienburg for the years 1414–1417 records the prices of well ropes made for various castles and order cities. The cheapest of them cost 13 and 14 shillings*, and the most expensive 1.5 marks and 1 cattle** and almost 3 marks. It must be assumed that the price depended on the material from which the ropes were made and their length. Some of them were certainly made of bast, like the rope used for the well located next to the Great Refectory in Marienburg [2].

Most castle wells had a shaft of a circular cross-section, despite the relative complexity of their construction. This was due to several reasons: with an equal perimeter length, the area of a circle is larger than that of a rectangle, and, as a result, a round well has a larger volume of water column than a rectangular one, and less material is needed for its manufacture, in addition, vertical loads on the walls of a round well lead to better sealing of the shaft lining. Therefore, there is reason to assume that those rectangular castle wells that are mentioned in documents or discovered during excavations were built as such due to a lack of funds or time, and subsequently they were supposed to be converted into round ones [2].

The diameter of the wells varied from 1.65 to 3 m, most being 2-2.5 m.

It can be assumed that the size of the wells depended on their purpose. Wells with a diameter of less than 2 m could be temporary or intended for small castle fortifications. Wells with a diameter of more than 2.5 m, although much more expensive and labor-intensive to implement, were built in larger strongholds. The well of the Königsberg castle had a diameter of 3 m [7].

The depth of the castle wells also varied and depended only on the depth of the aquifer. Obviously, where possible, the builders of the wells aimed to reach cleaner aquifers, avoiding shallower and often polluted layers. When determining the depth of the wells, one should also take into account the fluctuations in the level of aquifers in the historical perspective. For example, one of the wells of the High Castle of Marienburg is now 18 m deep, but in the times of the Order its depth reached 27 m [2]. The depth of the well in the castle of Stumm to the water table in 2012 was 24.5 m [8], and its total depth reaches 30 m, while the water in the well was of excellent quality even in modern times. The well in the courtyard of the castle of Königsberg had a depth of 13 m [3]. At the same time, the well in the Vogelsang castle (Mala Neshavka) had a depth of only 5.5 m [2].

In conclusion, it should be noted that the work on building the well in the castle was very difficult and not cheap. The order documents contain records of the costs of building the well in Ragnit Castle: in 1402, the carpenter Niklus Hollant was paid 2.5 marks for several weeks of work on the well. In addition to the actual diggers, carpenters, masons and even tinsmiths were also involved in such work. Special workers were also involved in maintaining the well in proper condition (monitoring the condition of the shaft lining, eliminating leaks, cleaning the bottom of the well, replacing filter materials, etc.).

There were cases when it was impossible to find a master to build a well on site, and the castle authorities had to conduct a long correspondence with the "center" asking to send them the necessary specialist. A striking example of this is the long-term epic with the construction of the already mentioned well in Ragnit.

The first written evidence of a well inside Ragnit Castle (there was another well on the forburg, and everything was fine with it) dates back to the autumn of 1402. Then, for several years (at least until the spring of 1409), there was an intensive correspondence between the commander of Ragnit and the supreme masters of the German Order, in which Ragnit asked for help, first of all, from people who could help solve the endless technical problems that the ill-fated well caused: not only was there little water in it, but it was also undrinkable due to the fact that the well shaft was either next to quicksand (dripsande), or directly in it, which caused constant leaks in the lining. In particular, it is clear from the correspondence that the work of removing water and sand from the well to eliminate leaks in the lining required the labor of at least 24 people, working day and night. In 1405, as many as 20 lasts*** of lime were sent to Ragnit (lime mortar, as already mentioned, was used for laying stones for lining the well shaft). In mid-August 1407, carpenter Hannus Andries arrived in Ragnit to work on the well with another unnamed craftsman. But the problems were not eliminated, since in December of the same year there is a mention of payment for work (10 marks) on hewing stones for the lining. It is unknown whether the problems with the well were solved in the spring of 1409, but the latest information that has reached us indicates that at this time hewn stone and a well winch were again sent to Ragnit [5].

Notes:

* Schilling is

a silver coin, 1/60 of a Prussian mark.

** Scot is

a monetary unit in the Prussian Order, 1 Prussian mark = 24 cattle, 1 cattle = 9

grams of silver.

*** Last is

a unit of volume of bulk solids (mainly grain), used in the 14th-19th centuries

in the ports of the Baltic Sea. It was equal to 3000-3840 liters.

Sources:

1. Vostrovska I., Petřík J., Petr L., Kočár P., Kočárová R., Hradílek Z., Kašák J., Sůvová Z., Adameková K., Vaněček Z., Peška J., Muigg B., Rybníček M., Kolář T., Tegel W., Kalábek M., Kalábková P. Wooden Well at the First Farmers' Settlement Area in Uničov, Czech Republic. — Archaeological Survey CXI (111), 2020, 61-111

2. Kulczykowski W. Study castle on the site of the Krzyzackie Państwa in Prusach, Masurian-Warminsky Community, no. 1 (279), 2013, p. 3–17.

3. Pawlowski A. Zamek w Sztumie. Residents of the City and Sztum County. Karpiny, 2007, 78 s.

4. Lahrs F. The Kingsberg Castle. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart, 1956.

5. Jóźwiak S., Trupinda J. Building a large castle of a Komturian peasant from the Renaissance at the end of the 14th – beginning of the 15th century and its subsequent construction, Kwartalnik Historii Kultury Materialnej, R. 57, no. 3–4, pp. 1–2. 339–368.

6. Castles and fortifications of the German Order in the northern part of East Prussia : Handbook / Auth.-compiled. A.P. Bakhtin; Ed. V.Yu. Kurpakov. Kaliningrad: Terra Baltika, 2005. 208 p.

7. Wagner W.D. The Kingsberg Castle: A Bau- and Cultural Studies. Band 1: From the birth to the reign of Friedrich Wilhelm I. (1255–1740). — Schnell & Steiner, 2008, p. 392

8. www.nowysztum.pl/serwisy/art/ciekawostki/c3.htm