Warmia and Masuria Plebiscite

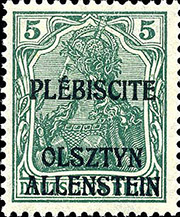

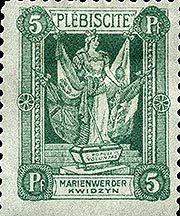

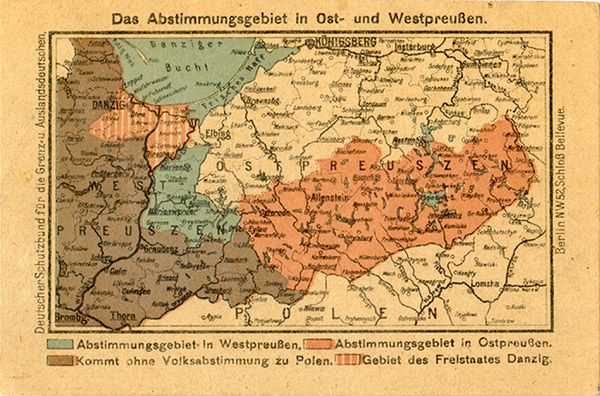

In the territory of the southern Krais (districts) of East Prussia and some Krais of West Prussia, in the second half of the 1920s, the construction of German territories in Pomerania and the province of Posen began - almost 44,000 square kilometers of land with a population of about 3 million people. The question of the belonging of the southern (Ermland and Masurian) districts of East Prussia and the territory of West Prussia, lying along the right bank of the Vistula between Marienburg and Marienwerder, where a significant number of ethnic Poles lived, was put to a plebiscite. Its initiators were the Poles themselves, whose delegation arrived at the Paris Peace Conference and demanded the annexation of German territories with a significant Polish-speaking population to Poland. The famous Polish politician Roman Dmowski (1864-1939), speaking at the conference, proposed to include in the future Poland not only those territories that eventually formed the Second Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, but also Pomerania with Danzig, the southern regions of East Prussia, almost the entire territory of present-day Lithuania, all of Upper Silesia, a significant part of Belarus, Volyn and Zhitomir region. Dmowski's proposal was rejected, but the question of the inclusion of part of the lands of East and West Prussia into Poland in accordance with Articles 94-97 of Section IX of Part of the Treaty of Versailles was decided to be put to a vote. The so-called Warmia-Masuria Plebiscite (in Polish terminology Plebiscyt na Warmii, Mazurach i Powiślu, in German – Abstimmungsgebiet Allenstein and Abstimmungsgebiet Marienwerder) was supposed to determine whether the inhabitants of these areas wanted to remain citizens of the Weimar Republic or would like to join Poland.

The plebiscite area included several krais: Ermland (Warmia) - Rössel (Reszel),

Allenstein (Olsztyn) and the city of Allenstein itself, Masurian - Oletzko

(Olecko), Osterode (Ostróda), Neidenburg (Nidzica), Ortelsburg (Szczytno),

Johannisburg (Pisz), Łyk (Elk), Lötzen (Gizycko), Sensburg (Mragowo) and

Powislin - Rosenberg (Susz), Marienwerder (Kwidzyn), Sztum and Marienburg

(Malbork).

Marienwerder and Allenstein were designated as the centers for preparing for the

vote.

The Poles created committees in support of the plebiscite, which were engaged in agitating the population for secession from Germany. Preparations for the vote were supervised by the League of Nations, which sent two observer commissions of five members each in February 1920. In the territory of the plebiscite, power passed from the Germans to the Allies, all German troops were to be withdrawn from these territories. They were replaced by Allied troops - a battalion of the Royal Irish Fusiliers and an Italian regiment stationed in Lyka and a battalion of Italian Bersaglieri together with a platoon of Frenchmen in Marienwerder. British officers were assigned to control the local police.

According to statistics, 557,001 people lived in the East Prussian territories (area 12,304.5 sq. km) (in 1919), and 161,183 people lived in the West Prussian territories (area 2,455 sq. km). Of these, 245,031 and 23,041 people respectively spoke Polish. As we can see, the percentage of the Polish-speaking population in the eastern territories was much higher than in the western ones. Not all residents were allowed to vote. In the east - 422,067 people (of which 371,083 people voted in July 1920), in the west - 121,176 people (104,842 people voted).

The period of preparation for the plebiscite was characterized by periodic outbreaks of violence against the Polish-speaking population in some areas and, as we would say now, the use of "black PR". To prevent pogroms in April 1920, Italian troops were transferred to Lötzen. But such cases did not become widespread. However, the Poles also periodically used unacceptable methods of influencing the population, both physical and ideological.

The plebiscite asked whether the inhabitants wanted their homeland to remain part of East Prussia (or become so for those who voted in Marienwerder) or instead become part of Poland. Surprisingly, the alternative for voters was not between Germany and Poland, but between East Prussia and Poland, given that East Prussia was not an independent territory, but only part of the Weimar Republic.

The right to vote was granted to persons who had reached the age of 20, were born in the territories of the plebiscite or had lived there since at least January 1, 1914. Voting was possible at the place of residence or, for those who had left their place of residence, at the place of birth. The Germans organized the transportation of people from Masuria who worked in western Germany (mainly workers and miners from the Ruhr), who arrived to vote by land and sea (via the port of Pillau).

The vote itself took place on July 11, 1920, and was held without incident or violation. The results of the plebiscite were discouraging for its initiators, the Polish nationalists. In the western regions, 7,947 people voted for joining Poland, and in the eastern regions, 7,924. In favor of remaining part of Germany (or more precisely, East Prussia), 96,895 and 363,159 people voted, respectively (data on the number of people who voted “for” and “against” differ in different sources. We present data from Rocznik statystyki Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej/Annuaire statistique de la République Polonaise 1 (1920/22), vol 2, Warsaw, 1923 — admin ).

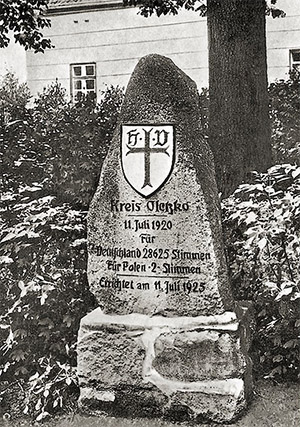

Only the inhabitants of three villages of the Krai of Osterode bordering Poland, as well as five villages in the district of Marienwerder, voted to leave Germany, and these territories were subsequently annexed to Poland. At the same time, in the Krai of Oletzko, only 2 votes were cast for joining Poland, while 28,625 votes were against. In honor of this, in 1928 the main city of the Krai, Marggrabowa, was renamed Treuburg (faithful city). To better visualize these numbers, imagine two columns: one 28 meters, 62 cm, and 5 mm high (the height of such a column is comparable to the height of the towers of some Heilsberg (Lidzbark Warmiński), Zinten (Korniewo), Insterburg (Chernyakhovsk), Seckenburg (Zapovednoye).

Monuments to the Warmia and Masuria Plebiscite

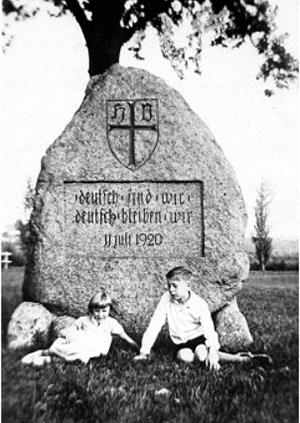

The plebiscite in Warmia and Masuria became a kind of compensation for Germany (and especially East Prussia) for the defeat in the First World War. The population of the cities and villages located in the plebiscite area voted overwhelmingly in July 1920 to remain part of East Prussia, and the territorial losses of this German province after the vote were minimal. Among the residents of the voting territories, inspired by the victory in the plebiscite, a spontaneous movement began to perpetuate this victory. It is difficult to say now who initiated this movement (unlike, say, the Bismarck towers or the "iron soldiers" ), but, be that as it may, in various cities, towns, centers of church communities and simply in individual villages, evidence of the victory of the German spirit over the Polish began to appear as a result of voluntary donations from citizens a year after the plebiscite. It should be noted here that some monuments bear the emblem of the East Prussian Aid Union (Hilfsverein für Ostpreußen) - the Gothic letters H and V inscribed in a Teutonic shield with a cross. Information about this organization is virtually non-existent, and we have not yet been able to understand its role in perpetuating the results of the plebiscite.

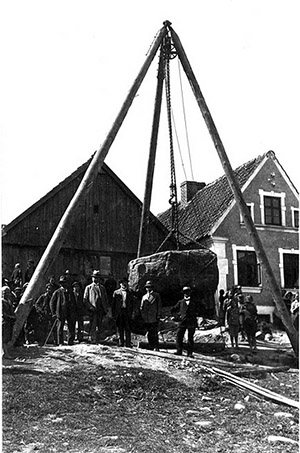

Just as with the monuments to those who died in the First World War , there was no single canon for the monuments to the Warmia-Masuria Plebiscite. Most of them were memorial stones of different sizes and shapes, installed in various places - from market squares and parks in cities to roadsides in small villages, and even in forests. In many ways, the type and size of the stones (and the form of perpetuation in general) depended on the amount of donations. In some places they limited themselves to planting trees, and in others to installing memorial plaques on existing monuments.

The number of all memorial signs in honor of the plebiscite is currently impossible to determine, but most likely there were more than a hundred. There are almost fifty reliable testimonies about such memorial signs. Many monuments were destroyed after the end of World War II. Recently, several stones have been discovered and installed in their former or new places.

One of these stones is located in the Collis Park in Ostróda (former Osterode). After World War II, the stone was overturned and gradually sank into the ground. It was discovered in 2002 by local historians and 10 years later it was put back in its original place.

Another stone was discovered in Olecko (former Treuburg). The stone stood in front of the town hall, built on the site of a former hunting lodge. The inscription on the stone reads:

Oletzko County • July 11, 1920 • for • Germany 28425 Stimmen • for Polen 2 Stimmen • Delivered on July 11, 1925

(Kreis Oletzko • July 11, 1920 • for • Germany 28425 votes • for Poland 2 votes • established July 11, 1925)

Currently, the stone is located in the utility room of Secondary School No. 1 (I Liceum Ogólnokształcące) on Zamkowa Street and there is no free access to it.

The town of Reszel (formerly Rößel ), once the center of the Krais, is rich in architectural and other monuments. In addition to the Gothic castle of the bishops of Ermland and the preserved urban development of the 18th-19th centuries, the town also has one of the few surviving monuments to the Franco-Prussian War in the territory of the former East Prussia, and the Tingplatz , and a monument to the Warmian-Masurian Plebiscite.

Few people guess the origin of the latter, since in addition to the fact that it is located quite far from the city center (at the intersection of Adam Mickiewicz and Wojska Polskiego streets), there is also no plaque with a dedication on the monument. After the end of World War II, a cast-iron plaque with the inscription "9.V.1945" was installed on the monument, but it is now missing as well.

In Bischofstein (now Bisztynek) a stone in honor of the plebiscite was erected just a year later, in July 1921.

The inscription on the stone read:

"Germany is here • Germany is here • July 11, 1920"

(Were Germans • Remained Germans • July 11, 1920)

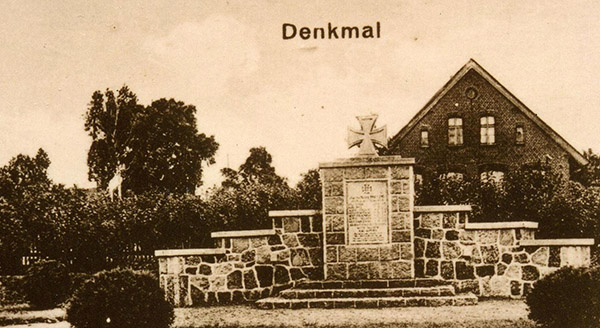

The use of existing monuments (or parts of them) for new purposes is not unique to the Poles or Russians. The Germans themselves installed plaques (or simply inscriptions) on existing monuments in honor of the plebiscite in Warmia and Masuria. This was the case, for example, in Weißenburg (now Wyszembork), when a plaque with the inscription was installed on a monument to the villagers who died in the First World War:

«DEN • HELDENTOD • … • ERRITTEN IM • WELTKRIEGE • 1914-1918 •

FROM THE HOUSE TO WEISSENBURG. • TO THE ERINNERUNG •

AN DAY • ABSTIMUNGSSIEG • AM JULI 11, 1920″ .

(To those who died heroically... in the World War 1914-1918

from the Weissenburg community in memory

In honor of the victory in the voting on July 11, 1920)

In the town of Gregersdorf (now Grzegórzki), an inscription was also added to the monument to the inhabitants who died in the First World War:

"The Stimulus Society of 1920 • 100 v. 100 for Germany • Make a German land. •

Give us your hand!

(Community vote 1920 • 100 out of 100 for Germany • Masuria is German land • Hands off, greedy Poles!)

The monument to the village of Paterschobensee (now Sasek Mały) who died in World War I was later given an inscription commemorating the results of the plebiscite:

"AM 11.7.1920 STIMMEN • WIR ALL GERMAN!"

(Voting on 11.7.1920. We are all Germans!)

But in some places, in honor of the plebiscite in Warmia and Masuria, individual monuments were erected. They can hardly be called outstanding; rather, they were modest in their execution and design, made either of hewn fieldstone or of brick covered with fieldstone.

The monument in Widminnen (now Wydminy) consisted of three stone blocks placed one on top of the other. Each block bore the inscription:

"HIER / IS DEUTSCHES / LAND"

«ZUR / ERINNERUNG / ON DEN / JULIUS 11 / 1920»

«DEUTSCH / GEBOREN / DEUTSCH / GELEBT / UND / DEUTSCH / GESTIMMT»

(This is German soil.

In memory of July 11, 1920

We were born Germans, we lived Germans, we remained Germans <voted>)

And finally, here are some archival and modern photographs of monuments in honor of the plebiscite in Warmia and Masuria.

In Lyck (now Ełk) a stone commemorating the Warmian-Masurian Plebiscite was first erected near the train station. It was then moved to Marktplatz and erected opposite the church, next to the monument to those killed in the Franco-Prussian War.

* Georg Gottheiner (1879 - 1956) - German politician, member of the German National People's Party and leader of the Johannisburg Landrat (1914-1930).

** Warmian chapels (Warmińskie kapliczki) are a characteristic element of small religious architecture in Warmia. They are small, usually stone, chapels, usually located at crossroads or by the side of roads. Inside them there may be a cross, a crucifix, a figure of the Virgin Mary, a lamp, etc. The oldest chapels have survived since the beginning of the 17th century, but most of them date back to the second half of the 19th – beginning of the 20th centuries. In total, there are more than 1,000 such chapels in Warmia.

Sources:

Kempa Robert. Masurian reminiscences of the past. The number of people in the 90s is very high. / Białostockie Teki Historyczne, t. 8/2010. — Białystok, 2010.

Statistical Collection of the Polish Republic/Annuaire Statistique de la Republique Polonaise 1 (1920/22), vol. 2, Warsaw, 1923.

Minakowski Jerzy. The base of the articles was collected by the plebiscites in Warmia, Mazury and Powis from 1920 . — Olsztyn, 2010.

Plebiscus in Warmia, Mazury and Malbork Lands . — Torun, 1930.

www.rowery.olsztyn.pl

www.marienburg.pl

www.sercemazur.pl

olsztyn.ap.gov.pl

www.ppt.ru

Bildarchive