First World War in the Romincka Forest

The military actions of the First World War (1914-1918), which took place in 1914-15 on the territory of East Prussia, did not bypass the Romincka Forest. From the very beginning of the East Prussian operation in August 1914 until the retreat of Russian troops in February 1915, the territory of the Forest was the arena of military clashes and the location of military units.

Thus, on August 17-19, 1914, troops of the 4th Army Corps of the Russian army passed through Pushcha and south of Lake Vishtynetskoye, invading East Prussia.

On August 20, the western outskirts of the Forest (the area of the villages of Gross Rominten and Kiauten) was the territory where episodes of the Battle of Gumbinnen-Goldap took place.

In September 1914, the German strike force had already driven out the retreating Russian troops and liberated settlements and the Pushcha territory from them.

In November, a second offensive by Russian troops into East Prussia took place, and local battles continued in the Pushcha area until January 1915.

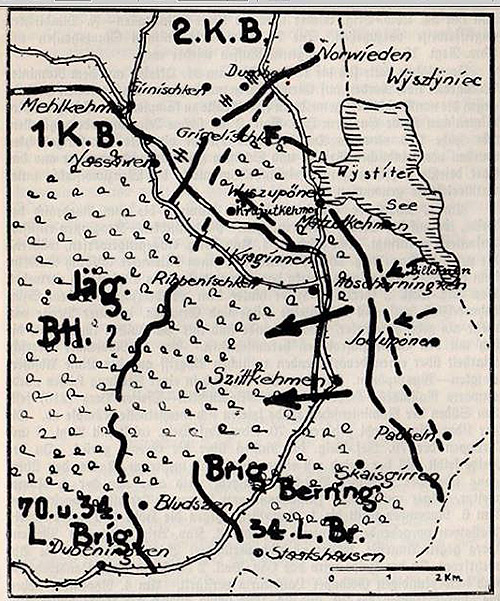

In February 1915, retreating Russian troops passed through the Pushcha again. For example, the 29th Infantry Division, when retreating from the front line, was located in the Pushcha, including near the hunting lodge in Rominten 1 . On February 12, 1915, a battle took place on the line between the village of Nassaven and Lake Vishtynetskoye, in which troops of the 27th Infantry Division took part.

The fighting brought a lot of damage and grief to the territory of the Romincka Forest. In August 1914, by order of the commander of the Russian army, General von Rennenkampf, almost all 250 buildings in the village of Gross Rominten were burned and destroyed. According to the "Announcement to all residents of East Prussia", signed by the commander of the Russian army, all villages in which resistance to the army is found are immediately burned, as a warning to the entire region:

“Yesterday, August 4, Imperial Russian troops crossed the Prussian border and are moving forward, fighting with German troops.

The will of the sovereign emperor is to pardon the peaceful inhabitants.

By the authority vested in me, I declare:

- Any resistance shown to the imperial troops of the Russian army by civilians will be mercilessly punished, regardless of the gender and age of the population.

- Villages where even the slightest attack is made or where civilians show resistance to the troops or their orders are immediately burned to the ground.

If the inhabitants of East Prussia do not display any hostile actions, then every little service they render to the Russian troops will be generously paid and rewarded.

The villages and property will be protected in complete inviolability." 2

Below are references to the Romincka Forest in the memoirs, diaries and diaries of direct participants in the events of the Great War. The references to the forest, settlements and residents are mainly cited, while direct descriptions and characteristics of the military actions that took place in the territory and in the area of the Romincka Forest are omitted. The author's text is provided with small comments and notes.

Memoirs of Vasily Iosifovich Gurko/Romeiko-Gurko (1864-1936), lieutenant general, commander of the 1st Army Cavalry Division as part of the 1st Army. In his memoirs, Gurko repeatedly mentions the Romincka Forest, where the troops under his command took part in military operations on more than one occasion.

This is how Gurko describes the Romintskaya Pushcha, calling it the “Romintskaya Forest”:

"At that time, the headquarters of the 5th Infantry Division was located in Suwalki. The regiments of this division had already been moved up to our border and occupied its section from the famous Rominten forest and sixty kilometers to the south. Emperor Wilhelm used to come to this very Rominten forest every year, accompanied by his closest friends and family members, to hunt deer. He usually invited representatives of the local Russian authorities, among whom the governor of the Suwalki province very often turned out to be. The well-known Colonel Myasoedov, who was then the head of the gendarmerie department in the border town of Verzhbolovo, located opposite Eydkuhnen, approximately one hundred kilometers from Rominten, was often there. < Here the narrator was clearly mistaken - Verzhbolovo (now Virbalis) is less than 25 km from the northern edge of the Rominten Forest and approximately 40 km from the village of Gross Rominten, if the general had in mind it. - admin >. Myasoedov was executed in 1915 after it was established that he was engaged in espionage for Germany. " 3

The following mentions the rangers who lived in the Pushcha territory:

“The offensive zone included the Rominten Forest, which Rennenkampf intended to bypass, skirting it from the south and north, in order to avoid forest battles, since the German units in this area had an advantage, provided by the help of rangers and hunters, whom Kaiser Wilhelm kept in his hunting grounds.” 4

Foresters and rangers deserved special attention from the Russian occupation authorities, since they were all armed as part of their official duties and also had service in ranger battalions and other units of the Kaiser's army behind them.

The incident that took place in August 1914 in occupied Insterburg, when, on the orders of the Russian command, the detained forester Greff, who served in the Johannisburg Forest, was shot, became widely known 5 .

The author also writes about the Kaiser's hunting lodge . But, apparently, he is mistaken or confused, since Wilhelm II's hunting lodge successfully survived the First World War, while the post office building and one of the forestry buildings were destroyed.

"In the following days, the forests around Rominten became the scene of the most fierce battles. The hunting lodge of Emperor Wilhelm, or rather its ruins, repeatedly changed hands. The battles, with varying success, lasted for several days, were fought on the very border." 6

Diary entries of Anatoly Nikolaevich Rosenshild von Paulin (1860-1929), who commanded the 29th Infantry Division as a lieutenant general in the 1st Russian Army. In them, the author describes the military events of the summer and autumn invasions of East Prussia.

He describes the Romintskaya Pushcha and its settlements in some detail in his diary entries:

"The further offensive had the goal of occupying Goldap and clearing the Rominten forest of the enemy in order to establish contact with the 53rd division. The Rominten forest belongs to Emperor Wilhelm. It is a dense forest intended for hunting goats, hares, pheasants and other feathered game. The entire forest is surrounded by deep ditches and high wire fences. It is crossed by the Rominta River and many good roads. In addition, [the forest] is cut into squares by wide, clear clearings, which can also serve as roads. Settlements closely surround the forest. Inside there are hunting villages for numerous administration, rangers and workers. The main one is Rominten, with Wilhelm's hunting castle, where our sovereign also visited on hunts 7 . The castle is large, surrounded by a park, and now contains many graves of our officers and soldiers. Then Jagdbude, where there was a school for huntsmen and dogs, and finally, in the south-west part of the farm, Terbude, K[lein] Jodup, Mit[tler] Jodup and Gr[oss] Jodup. The forest inside was stubbornly defended, especially in the direction of the castle and Terbude, where the road to Goldap led. Huntsmen also took part in the defense, and when we had already occupied the forest, we sometimes found inhabitants in it. Everyone was convinced that inside the forest in remote places there were dugouts in which huntsmen hid and, using their knowledge of the area, from time to time made their way to the German troops to report the information they had collected." 8

The mentioned graves of soldiers and officers raise some doubts, since according to researcher Max Dehnen 9 there was only one military burial in Rominten - Landsturm Geyer from the Landsturm battalion "Goldap" was buried in the local cemetery.

Next, Rosenshild von Paulin mentions the wildlife that the Romincka Forest was rich in. In reality, a large number of animals fell victim to poachers and to military action during the First World War. The number of the pride of the Forest, the red deer, alone decreased by more than 600 individuals.

“There were many hares and pheasants in the entire area where the division was located, and goats in the Rominten Forest. There were many hunters. <…> The Rominten Forest was guarded by one hundred Cossacks and two companies, and there were also various rear institutions there. Many of these units were obviously engaged in hunting, since I remember that the division headquarters officials twice ordered a goat from the Cossacks and each time they received it on time; for example, on Christmas.” 10

The winter retreat through the Romintskaya forest and rearguard battles are described in his memoirs by Alexander Arefievich Uspensky (1872 - after 1945). In the area of Lake Vishtynetskoye, he and his fellow soldiers had to save the regimental banner by dividing it into parts. 11

Military doctor Vasily Pavlovich Kravkov (1859-1920) was assistant to the head of the sanitary department of the 10th Army headquarters in the winter of 1914-1915. In his diary entries, he mentions Pushcha in the light of an inspection of hospitals in Shittkemen, Goldap and other nearby settlements in December 1914:

“From Goldap to Shitkemen, the road, by the way, ran through the royal hunting forest with deer, wild boar, chamois, and other animals abundantly found there.” 12

And further Kravkov describes the hospital of the Johannites in Schittkemen, which made an excellent impression on him.

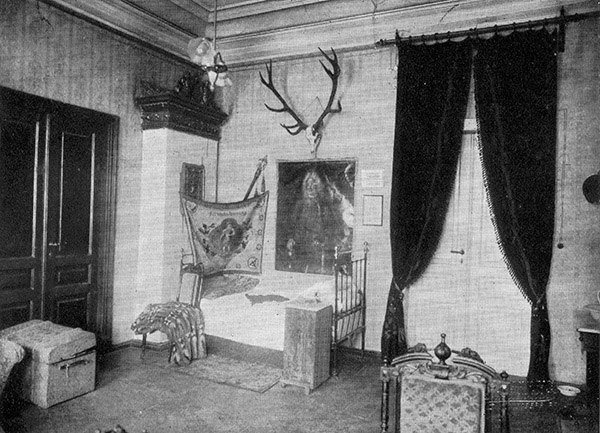

During the Russian occupation, the imperial hunting lodge in Rominten survived, but its interior was damaged, objects and inventory were looted, and furniture was partially burned. Already at the beginning of the First World War, with the beginning of border hostilities, the forester and caretaker of Rominten, Karl Zeidler , left Rominten, abandoning the imperial hunting lodge entrusted to him. For this reason, he fell into disfavor with Kaiser Wilhelm II.

The objects from Rominten subsequently appear in various places. Thus, in a photograph from the "home" of a Russian officer in Suwalki there is such a "trophy" from Rominten - deer antlers, and in addition to this there is also a portrait of Count Dönhoff from the officer's casino and a guild banner of the blacksmiths' guild from Goldap.

At the exhibition “War and Our Trophies”, opened on June 24, 1915 in Petrograd, among the war trophies there were on display an ashtray and a smoking pipe “from the hunting lodge of Emperor Wilhelm” 13 .

The war affected many settlements in the Forest. Heavy destruction was mainly in Goldap, Gross Rominten and Schittkemen. In the settlement of Rominten, the post office building, several residential buildings, including the teacher's house, and the Teerbude forestry were destroyed and burned.

And, of course, the war left military cemeteries in the Pushcha – silent reminders of past events. From large collective cemeteries (Goldap, Schittkemen, Dubeningken) to small burials of several people (Gross Rominten, Shelden, Grunwald) and individual graves (Warnen, Nassaven, Rominten).

Burials were formed mainly in existing village cemeteries, as well as in places of direct military clashes, where the bodies of the fallen were found. Only a couple of burials are unusual - military burials in the villages of Kiauten and Schlossbach, located on the outskirts of the Forest. There, the burials were located on Prussian hillforts.

The monuments dedicated to the memory of the First World War , erected in the mid-1920s in some settlements of the Romincka Forest , deserve special mention . These massive monuments, made of processed field stones, were located in the center of settlements or near settlement churches. To this day, in some settlements (Krasnolesye, Zhitkeimy, Dubeninki), these monuments have survived.

The restoration of settlements and the resumption of life in the Pushcha began during the First World War. Empress Augusta Victoria was the first to come to the rescue. She ordered trucks with food to be sent from Königsberg in quantities sufficient for the remaining population. Gradually, buildings began to be restored, the forest was cleared, and foresters took care of preserving the number of animals in the forest.

During the entire period of the First World War, Wilhelm II, like the Empress, visited East Prussia several times. But he only visited the hunting lodge once – in September 1917. On his way to Goldap via the Forest, he visited Rominten and Schittkemen. This was the last visit of the Kaiser to his hunting lodge in Rominten.

___________________

1. Rosenshild von Paulin A.N. Diary. Memories of the campaign of 1914-1915. - M., 2014. - P. 240-241. The author uses the old name of this settlement "Terbude".

2. East Prussian operation. Collection of documents. - M., 1939. - P. 252.

3. Gurko V.I. War and Revolution in Russia. - M., 2007. - P. 30.

4. Gurko V.I. Decree. comp. — P. 45.

5. Akkerman P.A. A month at army headquarters // Voice of the past. - 1917. - No. 9-10. - P. 319.

6. Gurko V.I. Decree. comp. — P. 91.

7. The Emperor’s stay in Rominten is erroneously indicated, since he never visited there.

8. Rosenshild von Paulin A.N. Op. cit. - P. 180.

9. Dehnen M. The war in East Germany from 1914/15. — Würzburg, 1966. — S. 127.

10. Rosenshild von Paulin A.N. Op. cit. - P. 208.

11. Uspensky A.A. At war. In captivity: Memories. - St. Petersburg, 2015. - P. 152.

12. Rossiysky M.A. 10th Army in East Prussia. Winter operations of 1914-1915 in the diary entries of V.P. Kravkov // News of the Laboratory of Ancient Technologies. - 2014. - No. 4 (13). - P. 50-51.

13. War and our trophies / M.K. Sokolovsky, I.N. Bozheryanov, L.E. Dmitriev-Kavkazsky and others. - Petrograd, 1915. - P. 26-27.