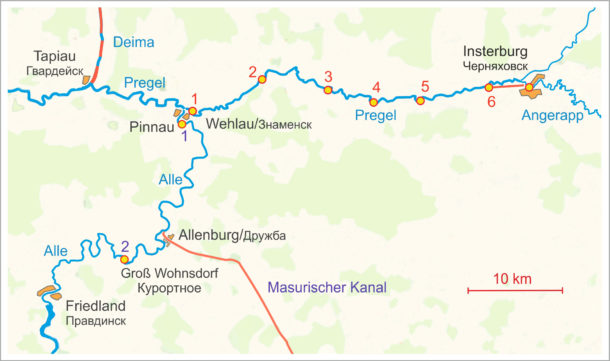

Pregel and Alla hydroelectric power station system in East Prussia

Background

Since ancient times, the main internal communication routes in the north of East Prussia were rivers, lakes and bays. But the shallow water and winding nature of the rivers made navigation difficult and required effective measures to improve the fairways. The first practical step in developing a river navigation network was taken in the Middle Ages, when in 1395, by order of the Grand Master of the Teutonic Order, Konrad von Jungingen, work began to straighten and widen the bed of the Daime River (now Deima, Kaliningrad Region). Later, the Daime actually became a deep shipping channel from Tapiau (Gvardeysk) to Labiau (Polessk). Then, over the course of four centuries, step by step, other rivers were straightened and deepened, large and small shipping channels were built. Particular attention was paid to the development of the Pregel River (Pregolya), the main waterway connecting the largest cities in the north of the province – Königsberg (Kaliningrad) and Insterburg (Chernyakhovsk). Since the 18th century, the banks of the Pregel have been actively strengthened, the riverbed has been straightened, and dredging has been carried out. As early as the early 1720s, a wooden mill dam and a small shipping lock were built on the Pregel near the village of Gross Bubainen (Berezhkovskoye). However, this did not significantly improve the shipping conditions of the Pregel on the 10-kilometer section from Insterburg to Gross Bubainen. Subsequently, the mill and lock were repeatedly rebuilt, and after a fire in the mid-1880s, they were dismantled [1].

Thus, by the beginning of the 20th century, due to the shallowness of the upper reaches of the Pregel, ships with a displacement of no more than 100 tons could pass to Insterburg, and only during the period of seasonal rise in the water level. At the same time, the depth of the fairway in the lower reaches of the Pregel allowed ships with a displacement of up to 250 tons to pass from Königsberg to Wehlau (Znamensk). This situation hindered the economic development of Insterburg and required the improvement of shipping conditions in the upper reaches of the Pregel. In the 1890s, repeated attempts were made to deepen the river bed in this section, but they did not bring the expected results. In the early 1900s, on the instructions of the Prussian Ministry of Public Works, a project was developed to increase the shipping depths in the upper reaches of the Pregel by constructing a cascade of hydroelectric power plants (HPP) on the river, consisting of retaining dams and bypass canals with locks. This method of increasing the navigable depth is called sluicing the river . In this case, the river is divided by the retaining dams of the hydroelectric power plants into separate pools*, within which the necessary navigable depth is ensured during the period of the lowest water level in midsummer (low water period) [2].

However, this project was soon revised in connection with the adoption in 1907 of another large-scale project – the construction of the Masurian Canal, which was to connect the Masurian Lakes with the Baltic Sea via the Alle (Lava) and Pregel rivers. The parameters of the canal corresponded to the standards of inland waterways of Germany for ships of the Finowmaß* class.

Obviously, the shipping parameters of the Alle and Pregel had to meet these same standards. As a result, the "General Preliminary Project for the Development of the Upper Pregel in the Section between Insterburg and Wehlau from 1911" was developed [3]. But this project was also postponed due to the protracted approval of the Masurian Canal construction project, and then the outbreak of World War I.

Finally, in 1920, the Prussian government adopted an expensive project for the locking of the Alle and Pregel, which proposed increasing the shipping depths of these rivers and thereby expanding shipping to Insterburg along the Pregel and to Friedland (Pravdinsk) along the Alle for ships with a displacement of up to 170 tons. Thus, this project became an integral part of the general plan for large-scale transformations of the shipping river network in the north of East Prussia.

Project

The Alle lock project included the construction of two hydroelectric power plants – GU No. 1 in Pinnau (urban district of Wehlau) and GU No. 2 in Gross Wohnsdorf (Kurortnoye). In Pinnau, it was planned to build a concrete and wooden retaining dam and a bypass canal with a lock. It was decided to use the dam of the planned hydroelectric power station in Gross Wohnsdorf and the shipping lock in its section as GU No. 2. Thus, the necessary shipping depth of the Alle up to Friedland was created by the dam of the hydroelectric power station, and up to the lower pool of this dam and the mouth of the Masurian Canal in Allenburg (Druzhba) – by the Pinnau dam.

A more complex and capital-intensive project of the Pregel locking envisaged the construction of five hydroelectric complexes on the Pregel and one distributed hydroelectric complex with a retaining dam on the Angerapp (Angrap) River, a bypass channel in Insterburg (Insterburg Canal) and a lock on the Pregel in Gaitsunen (Novaya Derevnya, now the territory of Chernyakhovsk). In addition, it was planned to build a river port in Insterburg, as well as to straighten and deepen the Pregel channel in some areas.

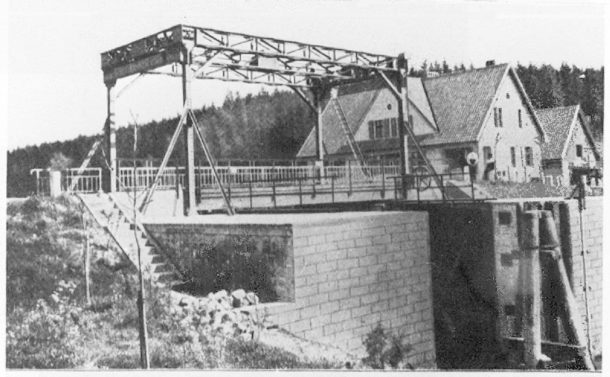

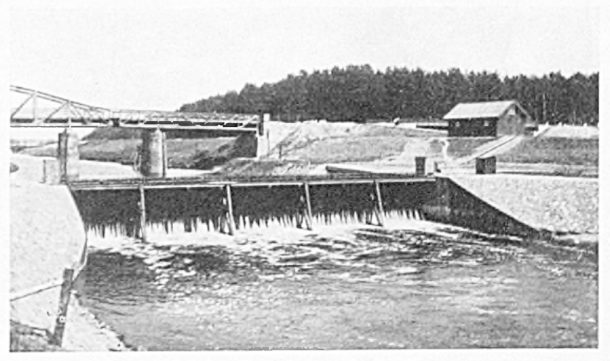

The number of hydraulic structures on the Pregel and the distances between them were chosen depending on the river slope so that the levels of the retaining pools they formed would provide the necessary shipping depth, but at the same time the water would not go beyond the main channel and the river floodplain would not be flooded. Bypass canals with locks on the upper pools of the dams are used to bypass the retaining dams. The peculiarity of the project was that the retaining dams on the Pregel are collapsible. They are installed only during low water and dismantled at the end of navigation for the winter. Then, during the next navigation, with the onset of low water, the dams are reinstalled. Thus, during the period of spring floods and "high water", when the fairway depth exceeds 1.7 m, shipping is carried out along the river, and during low water - through bypass canals and locks. Unlike the retaining dams on the Pregel, the retaining dam on the Angerapp is non-collapsible concrete. Its upper pool communicates with the bypass (Insterburg) canal by an underground water conduit and maintains a virtually constant water level in the canal. This locking scheme for the Pregel was intended to ensure regular cargo and passenger shipping in its upper reaches from Wehlau to Insterburg throughout the entire navigation period – from March to November [2].

The Pregel locking project included the construction of six hydroelectric power stations:

Wehlau (Znamensk), No. 1;

Taplaken (Talpaki), No. 2;

Voynoten (Shlyuznoye), No. 3;

Norkitten (Mezhdurechye), No. 4;

Shvegerau (Zaovrazhnoye), No. 5;

Gaitsunen (Novaya Derevnya) and Insterburg, No. 6.

The locks on the Pregel and Alla belong to the low-pressure class. The pressure* of the locks is from 1.3 to 2.2 m [2].

The locks of all waterworks, like the locks of the Masurian Canal, have standard useful chamber dimensions in length and width* (45.0 x 7.5) m.

The length of the sluiced section of the Pregel from Wehlau to Insterburg was about 55 km, the distances between the hydroelectric complexes were from 5 to 13 km [2].

Construction

In 1920, by order of the Prussian Ministry of Public Works, the Pregel Construction Directorate was established in Insterburg, which was entrusted with the management of construction and investment [3].

The construction of the hydroelectric power plants on the Alla and Pregel began in 1921. However, it was carried out with long delays due to the difficult economic situation in Germany, which caused interruptions in financing, supplies of construction materials and equipment. Already in 1922, financing of the work was sharply reduced due to the severe economic crisis and hyperinflation that broke out in Germany. Work was resumed only in 1924, when the country managed to achieve a certain economic stability. In 1921-1924, both hydroelectric power plants on the Alla were built. At the same time, the channel of the Pregel was straightened on the most winding and difficult for shipping section of Wehlau - Schwegerau.

In 1921, construction began on Hydroelectric Power Plant No. 6 in Insterburg - a retaining dam on the Angerapp, a river port, a bypass canal (Insterburg) and a shipping lock in Gaitzunen, as well as GU No. 5 in Schwegerau.

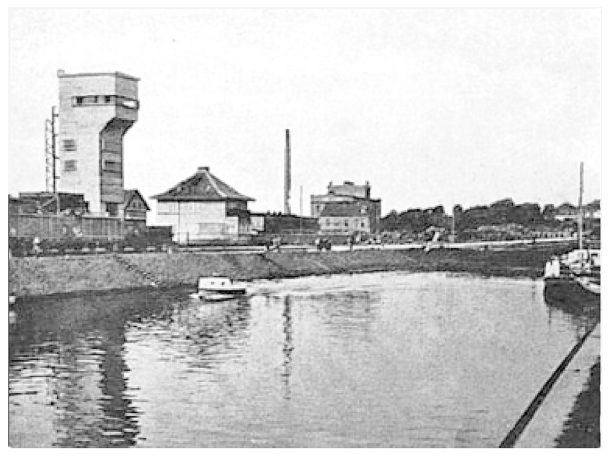

The 3.6 km long Insterburg Canal connected the port harbour with the Pregel via the Gaitzunen lock. The canal is laid in the floodplain of the Pregel and is surrounded by dams along most of its length. Since the channel bed and the port harbour are located above the Pregel, they are filled with water from the retaining pool of the dam on the Angerapp, which is connected to the harbour and the canal by an underground water conduit 300 m long. The parameters of the Insterburg Canal correspond to the standards of the Masurian Canal: the width along the water surface is 23 m, along the bottom - 13 m, the greatest depth is 2 m. The port harbour is 300 m long and 32 m wide, equipped with two berths and also includes a winter harbour in a triangular plan, typical of the Masurian Canal. It served as a mooring for transit and auxiliary vessels during the winter break in navigation, as well as for turning ships. A control tower, warehouses, loading and unloading platforms, service and administrative premises were built in the port, and railway lines were installed – with a normal gauge (1435 mm) and a narrow gauge (750 mm) [4].

Steel bridges on Pratt trusses, 30 m long, were erected across the Insterburg Canal - a combined road and rail bridge 0.7 km from the port and a road bridge 1.7 km away.

The opening of hydroelectric power station No. 6 and the river port in Insterburg took place in September 1926 [3; 4].

Since 1927, construction of GU No. 4-1 began sequentially from Norkitten to Wehlau. Work on this section was significantly complicated by the hydrogeological conditions of the Pregol floodplain. Bypass channels and pits for the lock chambers had to be dug in heavy moraine soils saturated with accumulations of huge boulders and pebbles. This also significantly complicated the driving of sheet piles. To protect construction sites from flooding during the spring floods of the Pregol, it was also necessary to build temporary earthen dams and fences made of Larsen piles. In addition, it was decided to build earthen dams and pumping stations for draining the polders and their economic use near the Wehlau, Taplaken and Voinoten GUs. In connection with this, the volume of work increased, additional capital investments and auxiliary equipment were required. The frequent flooding of the Pregel in 1928 led to delays in construction.

In 1927, earthen dams were built around the construction sites of the retaining dam and the Norkitten lock. Then a pit was dug for the lock chamber, and in March 1928, pile driving for the walls of the chamber began. The construction of the Voinoten State Institution proceeded in a similar manner.

In 1929, the global economic crisis broke out, which led to a sharp decline in production, the bankruptcy of many enterprises and an uncontrollable increase in unemployment. Construction on the Pregel was resumed only at the end of 1930, and already in 1931, the Norkitten and Voinoten GUs were finally built [5; 6]. After the end of the global economic crisis in 1933, the National Socialists came to power in Germany, who proclaimed a program to revitalize the economy of East Prussia, combat unemployment and create jobs. In 1934, work on the Pregel, as well as on the Masurian Canal, was resumed in full. Thanks to uninterrupted financing and the provision of preferential loans under the job creation program, already in the summer of 1934 a bypass canal with a lock, a reinforced concrete road bridge over the lock, a retaining dam, as well as an electrical substation, a pumping station and drainage canals near the hydroelectric complex were built in Taplaken.

And finally, in 1936, the last GU No. 1 Wehlau was put into operation [6]. An electrical substation, two pumping stations and drainage canals were also built here [5].

Thus, the project of locking the Alle and Pregel was implemented, and since 1936 regular cargo and passenger service has been opened between Königsberg, Insterburg and Friedland during the entire navigation period from March to November for ships with a displacement of up to 170 tons.

It should be noted that companies and banks from many cities in Germany and East Prussia participated in the construction of the hydroelectric power plants on the Pregel and Alla, and in the supply of special equipment and building materials.

The construction was carried out by consortiums:

Philipp Holzmann AG and Hermann Klammt, Wolf & Dörling and Wayss & Freytag - earthworks, construction of hydraulic structures and canals;

Dyckerhoff & Widmann AG (Karlsruhe / Berlin), Beton & Monierbau AG and Julius Berger AG – construction of locks and retaining dams.

Among many others, supplies of special equipment and building materials were provided by:

Uniongießierei (Königsberg), Schichau GmbH (Elbing) — steel structures and

sluice gates;

Vereinigte Stahlwerke AG (Dortmund) — Larsen sheet piles;

Cementvertriebsgesellschaft (Königsberg) — cement;

Steinfurt AG (Königsberg) — spokes* for retaining dams [4; 5; 6; 7].

In the summer of 1936, the Insterburg shipping company invited journalists on board their ship Insterburg for an excursion along the Pregel to Wehlau. This was the first trip with passengers. Before the Norkitten lock, they encountered the government ship Twiehaus, sailing from Tapiau. It had an excavator in tow. “Where to?” they shouted from the Insterburg. “To excavation work near Schwegerau,” answered the captain of the Twiehaus. This is how one of the journalists traveling on the Insterburg that day described the meeting [4].

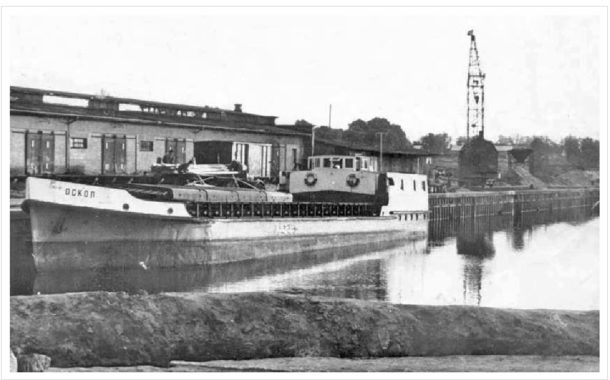

It is known about the intensity of shipping and cargo turnover in the direction of Insterburg and Friedland that self-propelled barges of the Finоwmaß class delivered building materials, coal, construction equipment and sand from the Norkitten quarries to Insterburg. From 1933 to 1936, cargo turnover on the Alla between Wehlau and Friedland increased from 18.2 to 27.8 thousand tons. The cargo-passenger motorboat "Ruth" traveled twice a week between Königsberg and Friedland. It was also rented for the transportation of small consignments of goods and for river excursions [8].

Thus, an important part of the unique water transport system of East Prussia was created, to which only one missing link remained to be connected – the Masurian Canal. Its construction was planned to be completed in 1941. Shipping to Insterburg and Friedland probably continued until the end of 1944. Having survived World War II, the shipping system on the Pregel worked properly for another half-century and served another country – the Soviet Union.

Post-war history

After the end of World War II, on the territory of the former East Prussia, which had become part of the USSR, a Special Military District (OsobVO) was formed on July 9, 1945. Only a year later, with the formation of the Königsberg/Kaliningrad Region, did the civil administration begin to be created here and the first Soviet settlers began to arrive. In July 1946, the Kaliningrad Technical Section of the USSR Ministry of River Fleet was created in Tapiau (since September 1946 – Gvardeysk), and the Pregel, Alle and Masurian Canal rivers with all their infrastructure were transferred to its jurisdiction [8].

In the first post-war years, there was an urgent need for building materials to rebuild the destroyed cities of the former East Prussia and the Soviet Union. In the conditions of post-war devastation and disrupted transport links, the most effective means of delivering bulk cargo was river transport, the fleet and infrastructure of which suffered less in the war than automobile and rail transport. In this regard, the Kaliningrad technical section immediately began restoring navigation along the Pregel to Insterburg, renamed in 1947 as Pregolya and Chernyakhovsk. It must be assumed that this was carried out with the help of German specialists who had remained in the region until that time. Later, they were replaced by Soviet technical personnel, who carried out the installation, adjustment of retaining dams and sluicing on the Pregel independently. As early as May 1, 1948, the Chernyakhovsk (former Insterburg) river port was put into operation, and spring navigation opened along the Chernyakhovsk (former Insterburg) Canal to Pregolya and further to Znamensk (former Wehlau) and Kaliningrad. And on May 27, the first steamship, the Krasnaya Zvezda, arrived at the Chernyakhovsk port from Kaliningrad at high water [9]. But the full restoration of the locks and retaining dams was completed only in September, so regular shipping during the entire navigation period from March to November was opened the following year. Captured dry cargo barges with a displacement of up to 170 tons, transporting sand from the Mezhdurechye (former Norkitten) quarries to Chernyakhovsk, were locked here, and passenger and transport ships sailed. Regular maintenance of the locks, retaining dams and riverbed was carried out by divers. The fairway was cleared of sand deposits and deepened with the help of dredges. In the second half of the 1980s, power electrical equipment for the drives of Soviet-made lock gates and electrical navigation lights began to be installed at the locks. However, the modernization of the locks could not be completed due to the economic crisis that began in the late 1980s and the subsequent collapse of the Soviet Union. Electrical equipment was installed only at three locks: in Novaya Derevnya (formerly Gaitzunen), Zaovrazhny (formerly Shvegerau) and Znamensk on the Pregolya.

The situation with shipping on the Lava (former Alle) was different. In the 1920s, the hydroelectric complex on the Alle in Pinnau/Wehlau was built primarily with the aim of providing a link between the Masurian Canal and the Pregel. However, since the prospects for completing the Masurian Canal were still unclear by the end of the 1950s, the restoration of shipping on the Lava was probably not given priority. And after the restoration of the Masurian Canal was deemed inexpedient at a Warsaw conference of representatives of the Polish Ministry of Waterways and Shipping and the USSR Ministry of Waterways in July 1958 [10], the issue of shipping on the Lava was removed from the agenda of the Kaliningrad Technical Section of the route (in January 1959, it was renamed the Guards District of Waterways and Shipping (GRVPiS)). As a result, in the mid-1970s, The Lava and the Masurian Canal were excluded from the List of Inland Waterways of the USSR and were left without technical maintenance and funding for their maintenance, although the lock in Znamensk (former Pinnau) remained on the balance sheet of the State Water Transport Inspectorate [8]. Their status has not changed to this day; they are still not considered waterways of the Russian Federation.

With the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 and the subsequent general economic decline in Russia, the intensity of freight and passenger traffic from Znamensk to Chernyakhovsk dropped sharply. There was virtually no scheduled maintenance of the waterways at that time, as a result of which shipping conditions on the Pregolya and Lava significantly worsened, and shipping safety dropped sharply. As a result, shipping and locking in the upper reaches of the Pregolya were completely stopped as early as 1995.

In the second half of the 1990s, due to temporary inaction of local authorities and protection of hydraulic structures, a predatory plunder of the metal equipment of the locks of the Masurian Canal began. Multi-ton lock gates, valves and other equipment, everything down to the fences, were removed. This destructive process also affected, although to a lesser extent, the locks on the Pregolya and Lava. Here, the mechanical and electrical equipment of the gate drives of some locks was partially dismantled. In the early 2000s, the locks were nevertheless taken under the protection of the GRVPIS and mothballed. In this situation, it made no sense to build retaining dams, since the locks did not work. This led to a general decrease in the water level in the upper reaches of the Pregolya and the upper pools of the bypass canals of all locks. The passage of large-tonnage vessels became possible only on the river during the period of "high water". As a result, the bypass canals (except for the Chernyakhovsky) became shallow and overgrown with reeds and bushes, the equipment of the retaining dams was lost, and the infrastructure of the hydroelectric power stations was virtually destroyed.

Thus, the water transport system that was created in the upper reaches of the Pregel in 1921-1936 and provided cargo and passenger transportation on ships with a displacement of up to 170 tons and a draft of 1.4 m, ceased to exist after 50 years.

Its revival in the near future seems highly doubtful due to the almost complete absence of transport and passenger river fleet, as well as the necessary financial and technical resources to maintain the necessary shipping conditions and water transport infrastructure in the upper reaches of the Pregolya. In addition, the demand and economic efficiency of passenger and freight transportation in the Pregolya-Lava basin remains uncertain. Thus, according to data for 2006, the role of water transport in the Kaliningrad Region in internal regional freight transportation was insignificant, and freight traffic significantly decreased - from 1 million tons in 1995 to 0.2 million tons in 2006. At the same time, intraregional passenger water transportation was not carried out at all [11]. It must be assumed that in connection with the economic downturn in Russia that began in 2008 and the reduction in funding, the situation with inland water transport in the Kaliningrad Region has only worsened by now.

At the same time, since the late 1990s, hiking, cycling, car and canoe tourism have been developing on the Polish section of the Masurian Canal. On the wave of interest in the Masurian Canal as a unique technical monument and tourist attraction, public associations emerged that actively promoted the idea of cross-border water tourism along the Masurian Canal and the rivers of the Kaliningrad Region. In 2003–2011, on their initiative, a number of regional conferences and symposia were held with the participation of representatives of the administrations of the Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship of Poland and the Pravdinsky District of the Kaliningrad Region. They published a joint declaration of intent, as well as conceptual documents on the development of water tourism and its infrastructure on the rivers of the Kaliningrad Region, including the Pregolya, Lava and the Masurian Canal [8; 12]. These documents were included in the agenda of the Polish-Russian Council for Cooperation between the Kaliningrad Region and the Northern Regions of Poland, and then sent for consideration by experts from both countries. However, in 2010, all projects were suspended until the Russian side resolved the issues of crossing the Russian border in water areas and using the internal waterways of the Russian Federation for shipping under a foreign flag.

It took many years of joint efforts by Russian and Polish authorities at all levels to change the situation. In May 2012, the inland waterways of the Russian Federation were opened to foreign sailing and pleasure craft. Russia was invited to join international cooperation on the issue of extending the trans-European waterway E70 through the territory of the Kaliningrad Region along the Masurian Canal, Lava and Pregola. In this regard, on 31.08.2015, Resolution No. 517 of the Government of the Kaliningrad Region was issued, which plans to restore the waterway along the Lava and the Masurian Canal to the border with the Republic of Poland, as well as the river port and canal in Chernyakhovsk for the period 2020-2030 [13].

As for the actual actions to restore the system of waterworks and shipping infrastructure on the Lawa and Pregola, as well as the Masurian Canal, as part of the trans-European waterway E70, these issues are the competence of the Federal Agency for Maritime and River Transport of the Ministry of Transport of the Russian Federation and the State Water Resources Administration "Wody Polskie" of Poland. Their solution requires, first of all, the political will of the governments of Russia and Poland, as well as huge investments. I would like to believe that such will will be demonstrated in the future…

From the author

I would like to express my heartfelt gratitude for the information provided and technical assistance to Vladimir Gusev, Galina Kashtanova-Erofeeva and Igor Erofeev, Lyudmila Safronova, Elena Pavlova, Bernd Gölz, Thomas Loov, Konstantin Karchevsky and Nikolai Tregub.

Dictionary of Special Terms

- Upper and lower pools are sections of a shipping channel/river with different water levels adjacent to a lock/retaining dam.

- Finowmaß is a type of vessel according to the classification of inland waterways of Germany in 1845 with the following characteristics: length – 40.2 m, width – 4.6 m, draft – 1.4 m, displacement – 170 t.

- Head is the difference in height between the lower and upper pools adjacent to a lock or retaining dam.

- The lock chamber is a sealed shaft-type chamber for accommodating a vessel during locking. It is sealed from the pools by upper and lower gates, as well as by the lock feeder system valves.

- Spokes are wooden vertical stopcocks of rectangular cross-section, from which the wall of a retaining dam is assembled.

List of sources and literature

- Gross Bubainen (Berezhkovskoye): the great history of a small village // The banks of Angrapa: artist-publicist. almanac. Kaliningrad, IP Mishutkina I.V. 2006. Issue 2: The case of Gennady Razumny: special issue / Ed. and compiled by I.V. Erofeev, G.V. Kashtanova-Erofeeva; author of the insertion of the article A.O. Vinogradov. Pp. 201-204.

- Breuer O . Channeling of the toppings. The Statuary Tape // The Bautechnik. Jahrgang. Berlin, 1935. 22. November. Heft 50. S. 663-666.

- The calculation of the average wages in Insterburg and Wehlau // The calculation of the average wage. 47. Jahrgang. Berlin, 1927. October 26. No. 43. 550-555.

- How Insterburg became a port city // The Shores of Angrapa: artist-publicist. almanac Kaliningrad, I.P. Mishutkina I.V. 2006. Issue 2: The Case of Gennady Razumny: special issue / Ed. and compiled by I.V. Erofeev, G.V. Kashtanova-Erofeeva; author of the insertion article A.O. Vinogradov. P. 135-136

- Schmidt K . The construction of the industrial complexes of Insterburg and Wehlau // The Bautechnik. 6. Jahrgang. Berlin, 1928. January 6. Heft 1. S. 14-18.

- Schmidt K . Construction of the equipment // The technology. 8. Jahrgang. Berlin, 1930. 29. August. Heft 37. S. 551-556.

- Breuer O . Channeling of the toppings. The Statuary Tape // The Bautechnik. Berlin, 1935. December 13. Heft 54. S. 746-749.

- Gusiev W . Rzeki Łyna, Pregoła and Dajma - from the water's edge from the Wielki Mazurskie Mountains to the Baltic Sea // Kanał Mazurski. The buildings are promising and promising in 100% growth rates. Symptomatic materials. Srokowo, 2011. S. 27-38.

- Erofeev I.V. Chronicle of the first post-war years. Insterburg-Chernyakhovsk: 1945 – 1950 // Banks of the Angrapa: artist-publicist. almanac / Ed. and compiled by I.V. Erofeev, G.V. Kashtanova-Erofeeva; author of the inserted article V.P. Khlimankov. Kaliningrad: IP Mishutkina I.V. 2009. Issue 3. Pp. 6-38.

- Bardun Yu.D. Masurian Canal. Technical structure: safety gates, ports and winter harbors, bridges and other structures. Post-war history of the Masurian Canal // Kaliningrad archives. 2018. Issue 15. Pp. 52-69.

- Gumenyuk I.S., Zverev Yu.M. Transport complex of the Kaliningrad region / Ed. G.M. Fedorov. Kaliningrad: Publishing house of the I.Kant Russian State University. 2008. P.45.

- "The Mazur Canal – water, water and juice." International conference. Wegorzewo, 03 December 2005 URL: https://yadi.sk/i/Q79IVLyTQPZg0g (accessed 09.04.2020).

- Resolution of the Government of the Kaliningrad Region No. 517 of August 31, 2015 On Amendments to the Territorial Planning Scheme of the Kaliningrad Region. (Main activities for the development of the transport complex. Water transport. Table 5, paragraph 6. Pp. 35, 36). URL: http://govru/vlast/agency/aggradostroenie/zip/schema/000_post_pko_31_08_15_n517.pdf (accessed: April 9, 2020).