Philocarty and Esperanto

Since the construction of the Tower of Babel, when the stern God took offense at people and made them speak different languages, humanity has used so-called "lingua franca" for communication - languages that were understood by the majority of the population of a territory. Such lingua franca once included Aramaic, Greek, Latin, French, and even the sign language of the North American Indians. Now the lingua franca for the countries of the former USSR and Eastern Europe is Russian, and the international lingua franca has become English.

At the end of the 19th century, there were attempts to create artificial languages that would become international lingua francas. Esperanto, developed by Lazar (Ludwik) Zamenhof (1859-1917) and first presented by him in Warsaw to his high school friends at the end of 1878, attempted to play such a role. Zamenhof subsequently improved the language he had created and in 1887 published the first Esperanto textbook in Russian under the pseudonym "Dr Esperanto". Esperanto experienced a surge in popularity in the 1920s, when it was even proposed as a working language for the League of Nations. But then Esperanto lovers were repressed first in the Soviet Union and later in Nazi Germany. According to various estimates, up to several hundred thousand people in the world now speak Esperanto to varying degrees.

The first Esperantist in Königsberg was the doctor Adolf Ebner. He became acquainted with the language back in 1897. Later, together with his associate Paul Fast, Ebner created the first Esperanto circle in Königsberg. By 1910, the number of members of this circle exceeded two hundred [1]. Esperanto courses appeared in the Albertina, and they were read for two groups of students - Germans and Russians. In 1914, a guide to Königsberg was published in Esperanto. The First World War interrupted the connections of Esperanto lovers around the world for several years, but immediately after the war, interest in the language was revived. In 1923, compulsory study of Esperanto was introduced for students of the Königsberg Higher School of Commerce. From 1925 to 1932, Esperanto programs were broadcast on the city radio twice a week. But with the coming to power of the National Socialists, who considered Esperanto to be the language of “Jews and communists,” the Esperanto movement began to fade, and in 1936 the language was banned altogether.

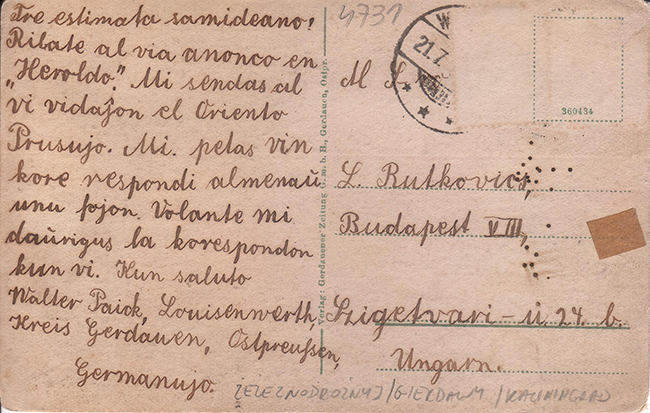

But let's return to our postcard. So, let's read:

Tre estimata samidanos! Ride through the window in "Heroldo". I sent you a video from Prusso Oriente. We drank wine and responded to a call. I voluntarily took the throne against you. Salute to Walter Paick, Louisiana Territory, East Germany

Dear like-minded person! Regarding the ad in the Geroldo. I am sending you a view of East Prussia. I ask you to respond at least once. I will be happy to continue our correspondence with you. With regards, Walter Paik, Luisenwerth, Kreis Gerdauen, East Prussia Germany

The front of the postcard shows the district administration building (Kreishaus) in Gerdauen (now Zheleznodorozhny), built according to the design of Friedrich Heitmann. The postcard is missing postage stamps, as is part of the postmark. Looking at the postcard itself, one can assume that it was published in the 1910-1920s.

Who was the sender of the postcard Walter Paik, we can only guess. The Luisenwerth he mentioned was located approximately in the middle between the villages of Vandlaken (now Zverevo) and Assauen (now Asuny, Poland), about a hundred meters north of the current Russian-Polish border, and was a folwark or estate (Gut). Now in its place there is a plowed field. It is unlikely that the sender was the owner of this estate. Or he was a very advanced Bauer, who had time not only to write postcards to other countries, but also to study Esperanto.

List of sources:

1. Goretskaya G. Esperanto in Königsberg and Kaliningrad . — Baltic Almanac, No. 9, Kaliningrad, 2010.