Masurian Canal Post-war history

…After the end of World War II and the capitulation of Germany by the decision of the Potsdam Conference in 1945, the territory of East Prussia was divided between the Soviet Union and Poland. As a result, Rastenburg) and the steel bridge across the canal. But the Nordenburg-Scandau railway line was not restored, since the city of Nordenburg (now Krylovo), by that time already populated by Poles, as a result of the unauthorized transfer of the border by the Soviet military authorities in the fall of 1945 ended up on Soviet territory, and the entire Polish population of the city was evicted [2]. The reinforced concrete bridge on this line was also not restored, and its blown-up spans still lie in the canal bed to this day. By the early 1960s, only 5 of the 13 destroyed bridges had been restored here. In addition, RZGW carried out repairs and strengthening of temporary construction dams in front of four unfinished locks, as well as siphons connected to the drainage system adjacent to the canal.

On July 9, 1945, a Special Military District (OsobVO) was formed on the territory of the former East Prussia, which had become part of the USSR, and all issues of organizing life and post-war reconstruction of the territory were resolved by the military authorities with the involvement of the remaining German population in the work [3, pp. 62-67]. Only a year later, with the formation of the Königsberg/Kaliningrad Region, a civil administration began to be created here and the first Soviet settlers began to arrive. In mid-1946, the Kaliningrad Technical Section of the route of the USSR Ministry of River Fleet (now the "Guards Region of Waterways and Shipping" - GRVPiS) was created in the Kaliningrad Region, and the canal, as a waterway, was transferred to its jurisdiction. Just as in Poland, here they first began to restore the destroyed bridges. Until the early 1950s, temporary wooden road bridges were erected (only 5 of the 18 destroyed), including those built into the locks. The supports of the remaining blown-up bridges still stand on the canal, as silent witnesses of the former infrastructure. Surprisingly, the only road bridge that was not blown up by the Germans has survived in the area of the now non-existent settlement of Mauenwalde. It is not used to this day, the road in it is abandoned.

Of the three railway bridges that existed before the war, only one was restored on the Insterburg-Gerdauen (Chernyakhovsk-Zheleznodorony) line, which became a double bridge (for Russian and European gauges). The other two railway lines were dismantled immediately after the war and were not restored.

After the deportation of the German population in 1947-1948, the territory on both sides of the border was abandoned. Many settlements were deserted, the roads leading to them lost their significance. Destroyed and abandoned houses were soon dismantled for bricks. Of the 30 settlements located near the northern part of the canal before the war, only 4 still exist - the settlements of Druzhba (former Allenburg), Novobiyskoye (Friedrichswald), Ozerki (Georgenfelde) and Zarechenskoye (Zobrost). And the hydraulic structures of the Soviet part of the Masurian Canal were simply abandoned.

In 1954, the first contacts between Polish and Soviet specialists took place in Kaliningrad on issues of inspecting the technical condition of locks and assessing the possibility of restoring the Masurian Canal for shipping and water use (flow from the Masurian Lakes). At that time, the locks in the Kaliningrad Region were still mostly in good working order, and the canal was filled with water. According to the recollections of residents of the Druzhba and Ozerki settlements, boats sailed along the canal and fish were caught. But for shipping larger vessels, it was necessary to clear the channel of the spans of the blown-up bridges. This was probably done by sapper units of the Soviet Army, which had the appropriate equipment and materials for blasting operations. The collapsed spans of the reinforced concrete bridges were crushed, and the debris was lifted up, dumped in heaps near their supports and remains there to this day. The spans of the steel road bridges were cut up and removed.

At the same time, work continued on replacing temporary wooden bridges with permanent reinforced concrete and steel ones, as well as restoring and replacing some of the hydraulic equipment of the locks that was damaged during the war or had fallen into disrepair. In this regard, technical problems arose at the oldest lock of the Masurian Canal - Allenburg I in the village of Druzhba when replacing the upper gates and installing a new, wider span of the steel built-in road bridge. To solve them, specialists from the branch of the Rosgiprovodkhoz Institute (now the Zapvodproekt Institute) in Kaliningrad were brought in, and they were given captured German technical documentation [4]. Today, it is difficult to determine what caused the irreparable damage to the lock - the damage during the war or the technical solutions of the institute's specialists and the bridge builders. But the fact remains that when installing the new bridge span, the left corner of the lower head was cut off along the shaft of the outlet gate, which is why the left water supply gallery of the lock supply system became inoperative. In connection with this, further work on the restoration of the Soviet part of the Masurian Canal was suspended.

In 1957, after lengthy adjustments and approvals, the treaty on the interstate border between the Polish People's Republic and the USSR was finally ratified. Then, in the Kaliningrad region, the border was demarcated on the ground and construction began on a system of engineering structures for the USSR border troops with a control and tracking strip and rows of barbed wire. As a result, the Masurian Canal was blocked by an earthen dam with flow pipes laid underneath, covered with steel gratings. This essentially put an end to the possibility of transborder shipping.

In 1958, a conference of representatives of the Polish Ministry of Waterways and Shipping and the USSR Ministry of Waterways was held in Warsaw, where it was recognized that the restoration of the Masurian Canal was inexpedient, as a waterway "of no interest to both sides." At the same time, it was proposed to mothball the canal's hydraulic structures. Thus, work on restoring the canal for shipping was finally curtailed on both sides of the border.

The period from the early 1960s to 1990

Apparently, the 1960s were a turning point in the fate of the Russian part of the Masurian Canal. About 55 years ago, for reasons that have not yet been determined, the water left the canal. 50-55 years is the approximate age of the oldest trees that grew in the dehydrated bed of the canal.

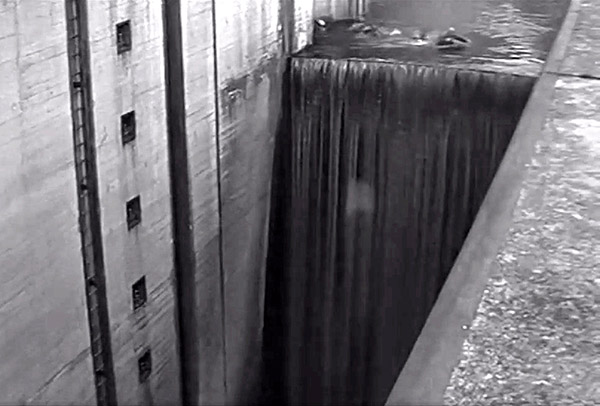

In addition, in the Soviet film “Spring on the Oder” shot in 1966-1967, it is clearly visible that the upper gates of the Georgenfeld lock are missing (or open), and water flows into the chamber directly from the threshold of the upper head, as it does today, i.e. there is practically no water in the canal anymore.

It is difficult to explain such a rapid disappearance of huge masses of water by natural causes - drying out or leakage through the hydraulic equipment of the locks, which were left without maintenance. It remains to assume that in connection with the decisions of the Warsaw Conference of 1958, as well as the impossibility of providing the necessary repair, maintenance and conservation of the locks and other hydraulic devices, the Soviet side decided to liquidate the Soviet part of the Masurian Canal as a waterway. In order to implement this technically, it was necessary to release water through the locks one by one from all sections of the Soviet part of the canal, opening the valves of the water supply galleries of the locks and the lock gates. The logic is understandable: no water in the canal - no waterway and no need for its maintenance. This version is to some extent confirmed by the testimonies of old-timers of the village of Druzhba about the series of spillways through the Allenburg I lock that took place in the mid-1960s, as a result of which water spilled onto the adjacent territory. This was also evidenced by the characteristic damage to the steel beams of the temporary gate shield on the upper head of this sluice, which were apparently bent by the hydraulic shock of a powerful flow of water. They have now been dismantled, but are still clearly visible in photographs from 1990 and even 2000.

Thus, by the beginning of the 1970s, the Soviet part of the Masurian Canal had effectively lost its departmental affiliation. If the reference book “Inland Waterways of the USSR” of 1975 still classifies the Lava River and the Masurian Canal as inland waterways and reports that “all hydraulic structures on the Lava River and the Masurian Canal are mothballed”, then on the map of waterways of the Kaliningrad Region of 1976 they are no longer designated as inland waterways [5]. As a result, the canal was abandoned, and the equipment of hydraulic structures and locks rusted and fell into disrepair due to lack of maintenance. Nature returned to its own - the canal bed and the slopes of the dams began to rapidly become overgrown with trees and bushes.

Later, due to a small flow of water in the dehydrated channel bed, coming from drainage ditches and streams, as well as precipitation, beavers began to build cascades of dams, and the channel in some areas filled with water to a depth of no more than 1 m. In shallow waters, this led to swamping and overgrowing of the channel bed with reeds.

Later, with the growth of economic activity, collective farms and forestry enterprises began to build unauthorized embankments across the canal with pipes laid underneath them. In some places, dams were cut to build crossings across the dewatered canal, but the crossings themselves were never built. Most of the siphons and almost all of the traps were also damaged or destroyed. This disrupted the water exchange between the canal and the drainage system and, in some cases, led to flooding and swamping of the adjacent area. There is a known case when a canal dam was used as a dam for a stream flowing under the canal through a siphon that was plugged. Here, too, a passage was made in the dam, through which water flowed into the canal bed when the resulting pond overflowed.

In Poland, the situation with the Masurian Canal was completely different. Here, from the very beginning, the canal administration (RZGW) was required to assume a higher level of responsibility for the technical condition of the Piaski/Sandhof lock, since a failure or breakdown of the lock mechanisms would have caused absolutely catastrophic consequences - huge masses of water from Lake Rydzówka could have flowed into the unfinished canal and flooded the area below. This would have caused significant damage to the lake itself. Therefore, the regional administration of RZGW ensured reliable protection and regular maintenance of the lock. Later, in connection with the decisions of the Warsaw Conference of 1958 and the lack of prospects for completing the canal and shipping along it, the administration took additional security measures - the roller shutter of the safety gate in front of the Piaski/Sandhof lock, as well as the upper gates and locks of the lock were blocked in the closed position. Apparently, since locking was no longer required in the current situation, the lock's storage basin gate and all electrical equipment, which were no longer needed, were dismantled. Thus, there was not a single authentic, fully functional lock left on the entire Masurian Canal. In the 1970s, the gaps in the upper gates were sealed at the Piaski/Sandhof lock, and all temporary construction dams in front of the unfinished locks were reinforced. Subsequently, these works began to be carried out regularly. However, it was not possible to ensure reliable protection of the remaining unfinished locks and other hydraulic structures of the canal. Some of their metal equipment was stolen.

The period from the early 1990s to the present

With the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 and the resulting temporary inaction of local authorities and economic chaos, in the mid-1990s, a total dismantling of metal equipment began at the locks of the Russian part of the canal - lock gates, shutters and other things, right down to the fences. Thus, all equipment of the Wilhelmshof and Gross Allendorf locks was completely dismantled, and to a large extent - the Georgenfelde lock. Partially, something similar happened with the locks on the Pregolya. Probably, this was carried out by people and organizations that had information about the technical design of the locks and the appropriate equipment for dismantling multi-ton structures, their loading and transportation. In 1997, only the intervention of residents of the village of Druzhba and the Consul General of the Republic of Poland in Kaliningrad prevented the dismantling of the lower gates and other equipment of the Allenburg I lock. This protest helped stop further looting of the locks.

As for the system of locks and retaining dams on the Pregolya, it continued to operate until 1985. Large barges transporting sand from the Mezhdurechye quarries (former Norkitten) to Chernyakhovsk were locked here. The locks were also modernized and Soviet-made power electrical equipment was installed. But with the collapse of the USSR, they also began to dismantle the equipment for the gate drives of some locks, as a result of which they became inoperative. Other locks were mothballed and placed under guard. In order to ensure navigation on the Pregolya above Znamensk, at least for small vessels, all retaining dams at the locks from Znamensk to Zaovrazhny were dismantled. This led to a decrease in the shipping level of the water in the Pregolya, a complete cessation of cargo and passenger shipping from Znamensk to Chernyakhovsk and the liquidation of the river fleet in this section. Thus, the water transport system that was created on the Pregel by 1936 and ensured the passage of ships with a displacement of up to 240 tons and a draft of 1.4 m, ceased to exist.

At the same time, walking, cycling, canoeing and car tourism had already begun to develop on the Masurian Canal in Poland, and accompanying infrastructure had spontaneously been created – information stands, parking lots, rope attractions, souvenir shops, etc. Public associations emerged that actively promoted the idea of cross-border water tourism along the Masurian Canal and the rivers of the Kaliningrad Region. On their initiative, a number of regional conferences were held with the participation of representatives of the administrations of the Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship of Poland and the Pravdinsky District of the Kaliningrad Region. A joint declaration of intent and conceptual documents on the development of water tourism and its infrastructure in the Kaliningrad Region were published at them. In 2003-2004, these issues were included in the agenda of the Polish-Russian Council for Cooperation of Regions of Poland and the Kaliningrad Region, and then sent for consideration by experts from the two countries [5, 6, 7].

It seemed that the divided Masurian Canal would once again become a single whole, and it would be possible to pass through it from start to finish by water and by land! However, in 2010, all projects were suspended until the Russian side resolved the issues of crossing the Russian border in water areas and using the inland waterways of the Russian Federation for shipping under a foreign flag. It took many years of joint efforts by Russian and Polish authorities at all levels for the situation to begin to change. Russia was invited to join international cooperation on the issue of continuing the trans-European waterway E70 through the territory of the Kaliningrad Region along the Masurian Canal and the Lava. This contributed to the fact that on 31.08.2015, Resolution No. 517 of the Government of the Kaliningrad Region was issued, which planned for the period 2020-2030 "the restoration of the waterway along the Lava River and the Masurian Canal to the border with the Republic of Poland" [8, pp. 35, 36].

However, despite this regulation, practically nothing is being done to increase the tourist attractiveness of the canal, to ensure its security and the necessary safety measures at the locks, which have no fences and there is a danger of falling from a great height. There are not even warning signs or inscriptions about this. In 2014, an information stand was finally installed at the Allenburg I lock, the only one on the entire Russian part of the canal. But this was done on the initiative and with the funds of the German Non-Profit Society of the Allenburg Church and a native of Allenburg from Germany, Mrs. Ute Bäsmann. The Masurian Canal, which is a unique technical monument de facto, deserves that the regional authorities officially assign this status to at least some locks, install information stands and ensure the security of the locks. Otherwise, the looting of the locks and the littering of the canal with household and construction waste will continue.

At the same time, as in Poland, enthusiasts are setting up a rope attraction at the Georgenfelde lock, and cleaning up the adjacent territory from garbage, bushes and trees. The interest of Kaliningrad Oblast residents in the canal locks and nearby historical sites is also growing. Amateur and organized groups of car, bicycle and walking tourists and adventure seekers regularly come here. Small groups of enthusiasts from different cities and towns of the Kaliningrad Oblast, together with their colleagues from Poland, continue to study the history and structure of the Masurian Canal and promote it as a unique technical monument of hydraulic engineering of the first third of the 20th century and a tourist attraction.

Thus, the history of the Masurian Canal continues. What next? Apparently, it should be recognized that as a waterway in accordance with the 1907 project, it will never be revived, since most of the hydraulic structures and locks of the canal can no longer be restored due to the irreparable technical damage caused to them over the past 75 years. In addition, at present, water transport of small rivers is inferior to road and rail transport economically and in terms of transportation speed. But the Masurian Canal can be used for tourism and recreation. With modern construction technologies, it is not technically difficult to complete the canal bed, connect it with the adjacent drainage system and fill it with water to a depth of about 1.5 m. In this form, the canal can be used as part of the trans-European waterway E70 for navigation of boats and yachts with a displacement of up to 5 tons. To do this, it will be necessary to clear its bed and dam slopes of trees and bushes, install gates on the upper heads of all locks of the Russian section of the Masurian Canal, complete the unfinished canal bed on the Polish section (about 2 km) and solve the technical problems of transshipment of ships at the locks from pool to pool. But, most importantly, it is necessary to solve the issues of crossing the border, as well as returning the status of the waterway and departmental affiliation of the Lava River and the Russian part of the Masurian Canal. This requires the political will of the governments of Russia and Poland and huge investments!

I would like to believe that this will come true one day, the Masurian Canal will come back to life and unite the peoples and countries of Europe...