Masurian Canal projects and construction

The Masurian Canal... This grandiose hydraulic engineering project was the logical conclusion of a large-scale transformation of the river network in the north of East Prussia, which began in the distant Middle Ages. In 1395, by order of the Grand Master of the Teutonic Order, Conrad von Jungingen, work began on straightening and widening the bed of the Daime River (now the Deima, Kaliningrad Region) [1, p. 122]. Later, the Daime actually became a deep shipping canal from Tapiau (Gvardeysk) to Labiau (Polessk). This was the first practical step towards creating a well-equipped river shipping network in East Prussia. Then, over the course of four centuries, step by step, other rivers were straightened and deepened, large and small shipping canals were built.

The construction of canals between the Masurian Lakes began in the mid-17th century. Even then, the idea of connecting the Masurian Lakes and the Baltic Sea via the Pregel River (Pregolya) arose, and Samuel Suchodolts (Sukhodolski), an engineer of Polish-Lithuanian origin in the Prussian service, developed several versions. However, the idea was only put into practice a century later. In 1764, on the initiative of the Ober-President of East Prussia Johann Friedrich von Domhardt, a new project for a shipping route linking Lake Mauersee (Mamry, Poland) and Pregel via the Angerapp River (Węgorapa, Poland/Angrapa, Kaliningrad Oblast), a tributary of the Pregel, was developed and adopted based on one of S. Suchodolts' projects. The necessary funds were allocated from the royal treasury, and construction work began on the Angerapp. However, when straightening and deepening the bed of this very winding and rapid river, the builders encountered major technical difficulties. The allocated funds became insufficient, and in 1775 the project was abandoned [2].

This idea was revisited only 100 years later due to the ongoing European wars that directly or indirectly affected Prussia. In 1862, a new concept was proposed and a project for a waterway shorter than the one along the river was developed. Angerapp, a route whose main link was a canal (a project by engineers Lange-Lentze). It connected Lake Mauersee with the Alle River (Lyna, Poland/Lawa, Kaliningrad Region), a tributary of the Pregel, in the area of the town of Allenburg (Druzhba, Kaliningrad Region). The 51.5 km long canal, called the Allenburg Canal, was to consist of seven horizontal sections connected by six land ramps along which ships would move on special rail trolleys using cable cars. By that time, the Oberlander Canal (Elbląg Canal, Poland) had already been built using this scheme. In this way, ships with a displacement of up to 100 tons had to overcome the difference in altitude of about 111 m between Lake Mauersee and the Alle River. For more efficient economic use of the canal, the project also provided for the construction of at the foot of the hydroelectric power station ramps. In 1874, the Prussian Landtag approved the canal project and allocated 9 million gold marks for its construction based on the free provision of land for the construction of the canal. However, many landowners refused to give up their land for free, setting speculative prices, which is why the approval and promotion of the project were delayed. In addition, with the advent of the steam engine, the transport policy of the Prussian state changed, and priority was given to the development of railways [3, p. 39]. As a result, funding for the project was stopped, and construction of the canal never began.

In the late 1880s, the canal project was revisited at the initiative of farmers in the Masurian Lake District, who were interested in the fastest possible delivery of their agricultural produce to the northern regions of East Prussia and further along the Baltic Sea to Germany in exchange for industrial goods, building materials and coal. In 1892, a canal project was submitted to the Prussian Parliament, which was named the Masurian Canal (designed by engineer Hess). It was fundamentally different from the previous project in that instead of inclined land ramps, it was proposed to build 7 locks (5 single and one double) on the same route – vertical ship-lifting elevators with useful chamber dimensions of (45.0 x 6.5 x 2.0) m [4, p. 197], which corresponded to the standards of inland waterways of Germany for ships of the Finowmaß1 class with a displacement of up to 170 tons. This made it possible to significantly increase the throughput capacity of the canal by increasing the displacement of ships and the speed of their transportation, since locking occurs faster and with less energy consumption than towing ships on land.

But soon this project was also sent back for revision due to problems related to the purchase of land plots for the construction of the canal, as well as protests from farmers in the floodplains of the Alle, Pregel and Daime rivers, who feared flooding of their lands due to the construction of retaining dams with locks on the rivers, as well as floods in the event of accidents at the locks. In addition, concerns arose that due to the high rate of water flow from Lake Mauersee into the canal (6 m3/s), it would be difficult to maintain the water level in the lake itself necessary for navigation, especially in the summer, and the movement of ships up the canal would also be difficult. [3, p. 41; 5, p. 64].

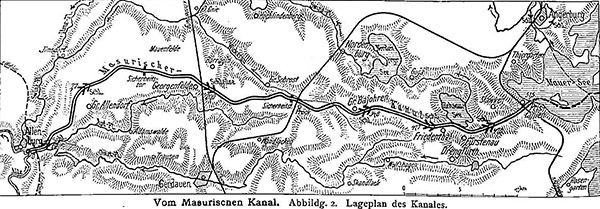

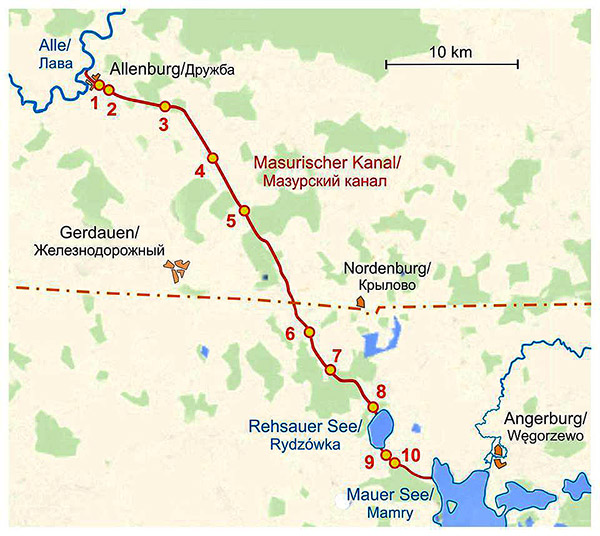

Thus, about 15 more years passed in the coordination and adjustment of the project, when, after consultations with residents of the areas of future construction, the issues of land reclamation and rational water use in the canal zone were finally agreed upon. In 1907, a new project was submitted to the Prussian Parliament for approval. Unlike the previous project, in it the canal route was laid through Lake Rezauersee (Rydzówka, Poland), and the total length of the canal was 50.4 km. This made it possible to reduce the length of the man-made channel of the canal by 5 km and reduce the area of purchased land and the volume of earthworks during construction. It was also decided to abandon the construction of hydroelectric power plants and to define the main function of the canal as transport, i.e. to use the water flow from the lakes only for sluicing. In addition, it was proposed to build several retaining dams with sluices on the Angerapp and Pissek Rivers (Pisa, Poland) in order to maintain the water level in Lake Mauersee necessary for shipping Finowmaß. It was also proposed to develop the adjacent lakes as reservoirs to feed Lake Mauersee with their water in dry years. In order to reduce the water consumption for sluicing, the design of the sluices was changed. Despite the fact that in the new project the number of sluices was increased to ten, the total water consumption for sluicing was reduced by reducing the height differences on the sluices and equipping the sluices with storage pools. Due to this, the maximum permissible flow rate of water from Lake Mauersee into the canal was reduced by half - to 3 m3 /s. In addition, the useful dimensions of the lock chamber were increased in width from 6.5 to 7.5 m and in depth from 2.0 to 2.5 m, which made it possible in the future to lock vessels of a higher class - Groß-Finowmaß with a displacement of up to 270 tons. Thus, thanks to the original technical solutions of German engineers, it was possible to significantly reduce the overall construction costs and improve the technical and economic characteristics of the Masurian Canal.

The locks were named after the villages near which they were built, in the order according to the project from the beginning of the canal on the Alla River (the minimum/maximum and nominal elevation differences at the lock are given in brackets):

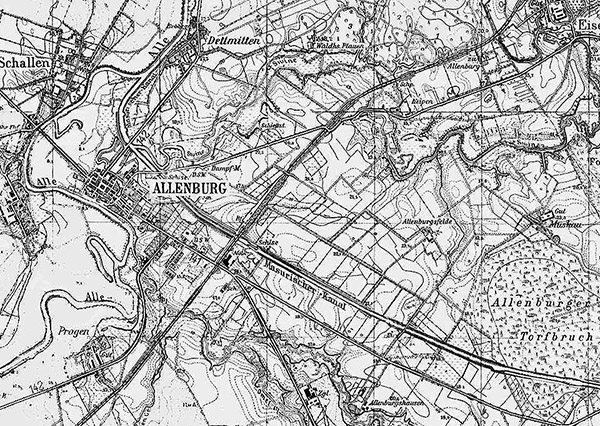

1 — Mündungsschleuse Allenburg / Friendship I (5.3/8.9 m).

2 — Bahnhofschluse Allenburg / Friendship II (8.0 m).

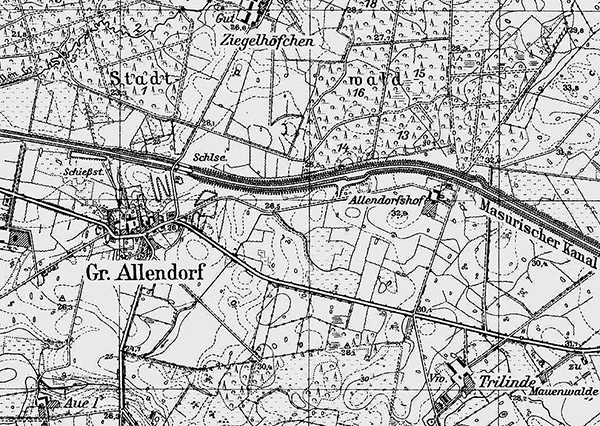

3 – Groß Allendorf (12.0 m).

4 – Wilhelmshof (7.5 m).

5 – Georgenfelde / Ozerki (15.5 m).

6 – Langenfeld / Długopole (6.5 m).

7 – Small Bajoren / Small Bajoren (10.5 m).

8 – Sandhof / Piaski (11.1/11.4 m).

9 – Fürstenau Underhill / Leśniewo Dolne (16.2/17.0 m).

10 – Fürstenau Oberschleuse / Leśniewo Mountain (16.5/17.1 m). [2]

On May 14, 1908, the Prussian parliament made the final decision to build the canal and allocated 16.515 million marks for this purpose. And finally, in April 1911, after lengthy project approvals at various levels, construction of the Masurian Canal began. To manage construction and investment in the northern and southern sections of the canal, the Prussian Ministry of Public Works created two construction departments in the city of Insterburg (Chernyakhovsk, Kaliningrad Region). The northern section, 28.4 km long, was located on the territory of the krais (administrative districts) of Wehlau and Gerdauen (now these are the territories of the Gvardeisky and Pravdinsky districts of the Kaliningrad Region). It included locks 1 through 5 and ran from the Alle River to the village of Pröck (now defunct) not far from the intersection of the canal with the Gerdauen-Nordenburg railway (now defunct). The southern section of the canal, 22 km long, with locks from the 6th to the 10th, was located within the districts of Gerdauen, Rastenburg and Angerburg from the village of Prök to Lake Mauersee (now these are the territories of the Kętrzyn and Węgorzewski counties of the Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship of Poland and partly the Prawdinsky district).

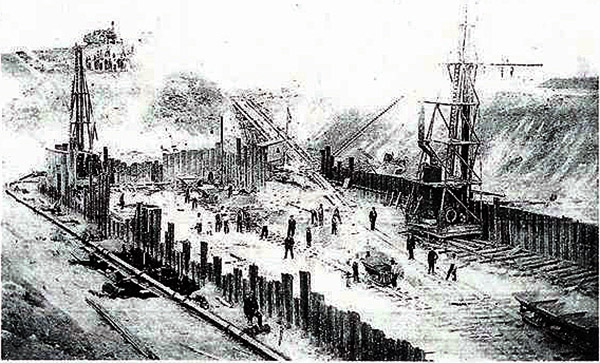

The companies Philipp Holzmann and Dyckerhoff & Widmann, which had experience in constructing hydraulic structures, were involved in the construction of the canal. The construction of the northern section was ahead of schedule, since the terrain here is flatter and less earthworks were required.

However, in 1914, construction of the canal was stopped due to the outbreak of World War I. By this time, about 75% of the excavation work had been completed and construction of three locks had begun [5, p. 65].

After the end of World War I, as a result of territorial redistribution in Europe, East Prussia lost part of its territory and became an exclave [as a result of the Treaty of Versailles in 1919, Danzig (Gdansk) received the status of a "free city", and part of the territory of Pomerania was transferred to Poland, which led to the formation of the so-called "Polish corridor", separating East Prussia from the rest of Germany. - admin ]. This disrupted the usual economic and transport links of the province with the rest of Germany and worsened its economic situation. Rail and road transit through Poland was subject to customs duties and was slowed down by border controls on goods. In the current situation, only internal river and sea transit remained independent. The Masurian Canal fit into the scheme of such transit in a natural way, which, presumably, played a decisive role in the resumption of its construction.

In 1920, by decision of the Imperial Ministry of Transport, which by that time had taken over the functions of the Prussian Ministry of Public Works, construction of the canal began again. But in 1922, funding for the work was sharply cut due to the severe economic crisis and hyperinflation that broke out in Germany, as well as a shortage of high-quality cement for the construction of locks. By that time, 20 km of the canal bed had already been dug and 10 km were under construction, construction of most of the locks had begun and one of them, Allenburg I, was completely built. [5, p. 65].

But even in the conditions of the crisis in connection with the construction of the Masurian Canal in 1920, the Prussian government adopted an expensive project to modernize the hydraulic structures of the entire shipping network in the Pregel basin to the standards of German inland waterways for Finowmaß-class vessels. In 1921-1924, in the city of Wehlau (Znamensk, Kaliningrad Region), a retaining dam and the Pinnau bypass lock were built to raise the water level in the Alla. At the same time, on the section from Insterburg to Wehlau, they began to straighten the Pregel channel and build six retaining dams and locks. All of them, like the locks of the Masurian Canal, had standard useful chamber sizes in length and width - (45.0 x 7.5) m. However, due to the global economic crisis that broke out at the end of 1929, all work was practically curtailed.

After the end of the crisis in 1933, the National Socialists came to power in Germany and proclaimed a program to revitalize the economy of East Prussia. Construction on the Masurian Canal and the Pregel was resumed. In 1936, after the last lock in Wehlau was put into operation, the Pregel became navigable along its entire length [4, pp. 1-39; 6, pp. 201-203]. Thus, the construction of the Masurian Canal directly influenced the further development of shipping along the Pregel and Alla, ensuring regular transport and passenger service.

Work on the Masurian Canal resumed in 1934. Construction was planned to be completed by May 1941. At first, the pace of work was quite high, thanks to uninterrupted financing and increased mechanization of earthworks. In 1936, the construction of the Masurian Canal was the second most capital-intensive project in East Prussia after the Berlin-Königsberg Autobahn.

Construction was carried out day and night. In winter, during severe frosts, they were interrupted only for a short time. The modernization of the hydraulic structures of the Masurian Canal was actively carried out, new technical solutions and advanced construction technologies were introduced. Excavators and concrete pumps were used for the first time, and welding instead of riveting was used in the production and installation of steel structures.

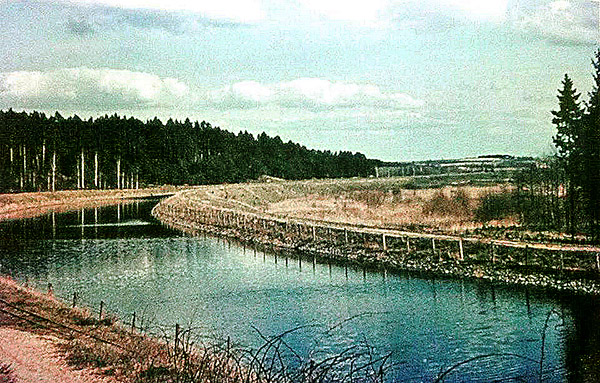

In order to increase the channel's capacity and ensure two-way traffic, it was decided to widen the channel from 12 to 23 m and deepen it to 2.5 m. This required rebuilding the dams and increasing the length and height of the bridge spans. Steel bridges with longer and higher spans were built instead of reinforced concrete bridges. In this regard, the question arose of dismantling the already built reinforced concrete bridges and replacing them with steel ones. But in the end, it was decided to keep the reinforced concrete bridges, sacrificing some narrowing of the channel at their supports.

Contrary to popular belief that the construction of the canal was strictly classified, since the canal was supposedly intended to be used to transport U-II submarines [submarines on the Masurian Canal, underground factories and airfields located on the territory of East Prussia, as well as numerous dungeons under Königsberg/Kaliningrad are common myths that still exist among the population of the Kaliningrad region, which pseudo-experts in pre-war history like to regale gullible tourists with. — admin ], both the canal projects and the construction itself were widely covered in technical journals and newspapers in Germany and Poland.

With the outbreak of World War II, forced labor of prisoners, war captives, and foreign workers from occupied territories began to be used on the canal. Paramilitary labor units of the Reich Labor Service (RAD) were also involved in the work. The war with the Soviet Union, which began in 1941, required Germany to mobilize all economic, material, and human resources. Construction of the canal slowed sharply due to a shortage of building materials and labor, which were directed toward the construction of bunkers for the headquarters of the Supreme Command of the Wehrmacht in Mauerwald (Mamerki, Poland) and Hitler's headquarters "Wolfschanze" ("Wolf's Lair") near Rastenburg (Kętrzyn, Poland). And in 1942, after a radical change on the Eastern Front and the beginning of the offensive of Soviet troops, it was completely stopped. By this time, the readiness of the canal and its hydraulic structures was about 70%. In the northern section of the canal, almost all five locks were ready. In the southern section, only one lock, Sandhof, was completely ready. The readiness of the other locks ranged from 15 to 65%. The entire canal bed in the northern section and partly in the southern section was already filled with water to the design depth of 2.0-2.5 m. Three safety gates, 31 of the 32 road bridges envisaged by the project, 5 railway bridges, 19 houses for service personnel and lock guards, 14 siphons under the canal bed and 7 culverts were also built [2; 5, p. 53; 6, p. 203].

In 1944, Soviet troops entered East Prussia. Although the canal and its dams up to 12 m high in some areas already represented an insurmountable water obstacle for the advancing Red Army, the Wehrmacht additionally strengthened them with land lines of defense made of barbed wire, trenches, fire points, anti-tank hedgehogs and concrete "babas" at the approaches to the bridges. Probably, the German administration of the Masurian Canal also took measures to prevent a catastrophic discharge of water into the canal in the event of damage to the locks during military operations. In addition, emergency stopcocks were installed and the upper gates and locks of the Sandhof lock, as well as the safety gates at the exit from Lake Resauersee, were blocked in the closed position. In early 1945, during their retreat, the Germans blew up all the bridges across the canal (except for one automobile bridge on the northern section of the canal) [6, p. 202]. But all the locks, security gates, temporary construction dams and canal dykes in sections already filled with water remained intact. During the fighting, they also suffered virtually no damage, presumably due to the common sense of the warring parties, since the local population and refugees still remained in the canal zone. Therefore, catastrophic flooding of the territory did not occur.

After the end of World War II and the capitulation of Germany, the territory of East Prussia was divided between the Soviet Union and Poland by the decision of the Potsdam Conference in 1945. As a result, the Masurian Canal was cut by an interstate border , which crossed out not only the canal itself, but also the unity of the plan. The integral organizational system with specialists and technical documentation, material and technical resources ceased to exist. In order for the Masurian Canal to function as a waterway, it was necessary to drain large volumes of water from the Masurian Lakes to the Alle River along a chain from lock to lock. But it was impossible to do this in the unfinished canal, as well as to continue construction in the conditions of post-war devastation and the division of property of the canal.

This is how this unique project, which for centuries inspired the imagination of many generations of people in East Prussia, ended its journey...

But the canal did not disappear, it still exists. It just began another story - the post-war one. It is no less dramatic and contains many secrets that are waiting to be solved.

_______________________

Dictionary of Special Terms

1. Vessel displacement (maximum), t – the mass of the entire vessel with crew, water supply, fuel, lubricants and cargo.

2. Finowmaß is a type of vessel according to the classification of inland waterways of Germany in 1845 with the following characteristics: length - 40.2 m, width - 4.6 m, draft - 1.4 m, displacement - 170 t.

3. Groß-Finowmaß is a type of vessel according to the classification of inland waterways of Germany in 1845 with the following characteristics: length - 41.0 m, width - 5.1 m, draft - 1.75 m, displacement - 270 t.

4. The sluice heads, upper and lower, are reinforced concrete power structures that absorb the pressure of the water from the upper pool and the filled chamber.

5. Upper and lower pools are sections of the shipping channel with different water levels, adjacent to the lock heads.

6. Lock chamber – a reinforced concrete shaft-type structure between the lock heads for accommodating a vessel, raising and lowering it by equalizing the water level in the chamber with the water levels of the upper and lower pools. The chamber is sealed from the pools by the upper and lower lock gates at the lock heads, as well as by the lock feeder system gates.

7. A valve for shutting off the water supply gallery of the power supply system.

8. Saving pool – an open pool for collecting water and reusing it during sluicing. It is located on the outside of the chamber. During downward sluicing, some of the water from the chamber is drained into the saving pools and then used to fill the chamber during upward sluicing.

9. Safety gates – a protective hydraulic structure. Designed to block the channel bed in the event of a lock failure.

10. Temporary construction dam (TCD) – an earth dam or a dam made of Larsen sheet piles, constructed in the channel of a canal in front of a lock under construction. The canal in front of the TCD is filled with water, and then, after the construction of the lock is completed, the TCD is dismantled.

11. A siphon is a pipeline for drainage ditches and streams crossing a canal. It is laid under the canal bed and is a U-shaped or straight inclined concrete pipe.

Bibliography

1. East Prussia. From Ancient Times to the End of World War II / V.I. Galtsov, V.S. Isupov, G.V. Kretinin, V.I. Kulakov, and others. Kaliningrad, 1996.

2. Masurischer Kanal. URL: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Masurischer_Kanal (accessed 05.04.2018).

3. Sarnowski R. Mazurski Canal. Masurischer Canal. Olsztyn, 2010.

4. From the Masurischen Canal. German Newspaper. XLII. Jahrgang. № 30. 11 April.

5. Stachowski K. 100 lat Mazursky Canal. Odkrywca. 2011. No. 9 (152).

6. Bardun Yu.D. Mazur Canal. History of creation, projects, construction. Kaliningrad archives. 2016. Issue 13.