Iron soldiers of the First World War

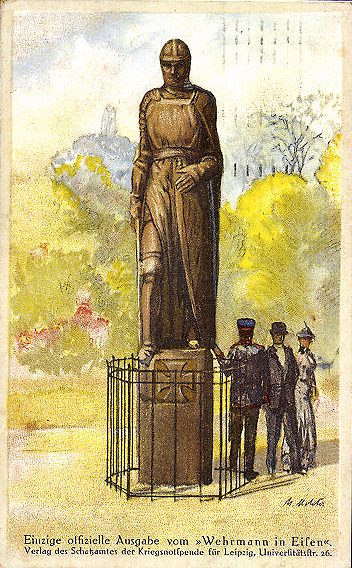

"Warrior in Iron" or "Wehrmann im Eisen" (also Eiserner Wehrmann - "iron warrior", Nagelmann - "man of nails") is a symbol of German propaganda during World War I. It is one of the examples of numerous charity events of that time , aimed at raising funds for the families of fallen soldiers, as well as for the treatment of the wounded.

The tradition originally began in Vienna in the 16th century. There, at Stock-in-Eisen-Platz 3, there is still a spruce tree trunk into which passing blacksmiths hammered nails, believing that this would bring them good luck.

The first action of hammering nails into a wooden sculpture of a medieval knight in full armor also took place in Vienna on March 6, 1915. This knight, called the "iron soldier", later served as a model for many, many wooden sculptures. The idea of hammering nails became widespread. On the initiative of the then Landgravine of Hesse-Darmstadt, on April 23, 1915, a wooden cross was created in Darmstadt for hammering nails, and later the action began to spread to various cities of Austria-Hungary (for example, in Budapest, Lviv, Chernivtsi, Drohobych, Prague) and Germany (Berlin, Wismar, Lubeck, Leipzig, Breslau, Metz, Cologne, etc.), and even to San Francisco, Istanbul, Sofia, Buenos Aires.

Already in the summer of 1915, wooden (mostly oak) statues of warriors appeared in the central squares and parks of many German cities — a modern embodiment of the allegorical sculpture of a defender: Rolands, Siegfrieds, Heinrichs, Saints Michael and George, and later Field Marshal Hindenburg, the savior of Germany from the invasion of the Russian army. Special plates or shields with the image of the Iron Cross, city coats of arms, imperial eagles or even triumphal columns were also used to hammer nails. By making a donation, everyone who wanted to would receive a nail and hammer it into a wooden statue. There were three types of nails: iron, silver and gold, each with its own specific price — from 50 pfennigs to 50 gold marks. Moreover, all three types of nails were iron, but covered with black, silver or gold paint, respectively. Gradually covered with nail heads, the wooden monuments became iron, which is where their name came from. Iron soldiers enjoyed considerable public attention and contributed to the patriotic upsurge among the population. Non-participation in these actions was often considered a lack of patriotism. There were citizens who donated large sums, exceeding the cost of the most expensive nail. For them, there were metal plates on which the name and surname of the donor were engraved. The plates were then placed on the sculptures.

In addition to selling nails, there was also trade in postcards, patriotic brochures, medals and other souvenir paraphernalia.

Many wooden sculptures were created by famous sculptors and artists of the time. Participants in the actions were awarded with certificates or commemorative badges. And after the end of the war, many sculptures of soldiers became national cultural monuments and were transferred to museums and town halls, where they were kept as an honorary testimony of patriotism and unity of the nation during the difficult war years.

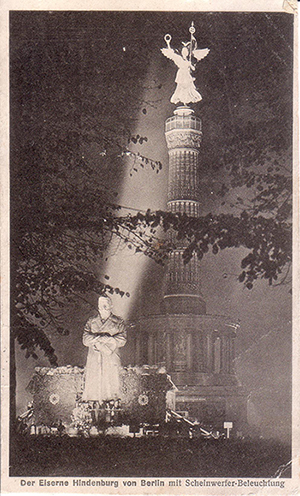

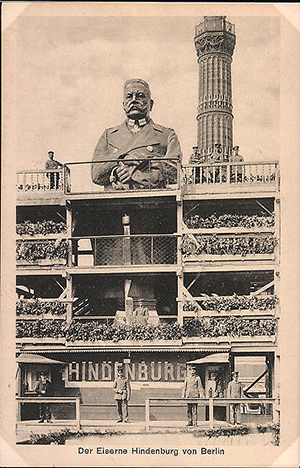

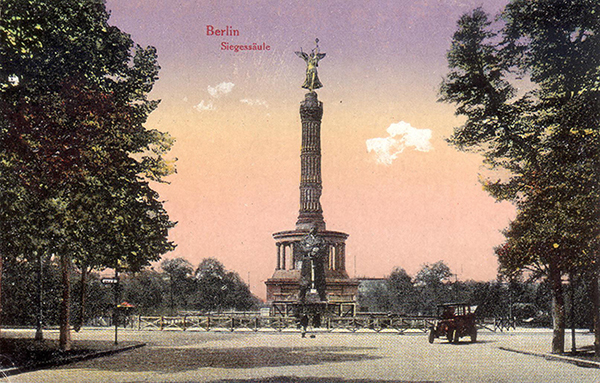

The largest sculpture was in Berlin, it was a 12-meter (data on the size of this object in different sources differ) statue of Paul von Hindenburg, installed on Königsplatz, next to the Victory Column. Its opening took place on September 4, 1915.

This is how V. Pikul describes this tradition in his novel “I Have the Honor”:

“Soon all of Germany was covered with monuments to Hindenburg.

The shortage of non-ferrous metals forced the Germans to immortalize Hindenburg with monuments made of planks. The first such monument was erected on Berlin's Lutzowufer Embankment. Hammers and piles of nails always lay near the roughly painted "wooden thing." Every German who wanted to express his patriotic enthusiasm paid a tax, receiving a nail, which he then hammered into Hindenburg. There was no end to the patriots, and very soon the wooden monument to Hindenburg turned into an iron one, all studded with nail heads.

This monument also contained the nails that the German Social Democrats had driven into it with great pleasure…”

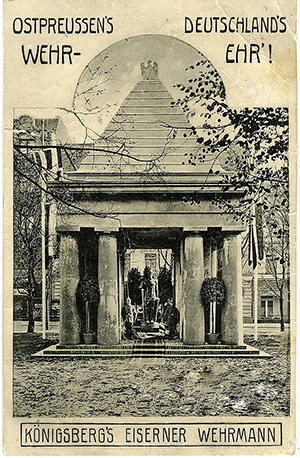

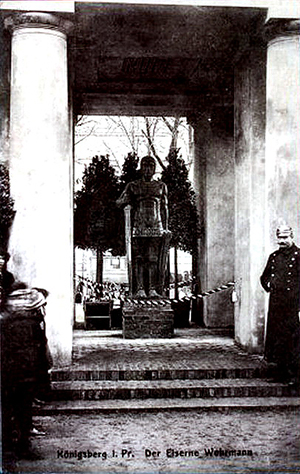

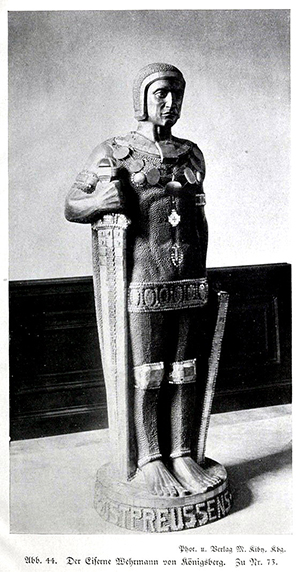

The patriotic action with iron warriors did not bypass East Prussia. For example, in Königsberg, a sculpture of a warrior (the work of the famous Königsberg sculptor Stanislav Kauer) was installed in a special rotunda on Paradeplatz. It stood there from October 1915 to June 1916. The sculpture was created in honor of the memory of the fallen soldiers of the 1st Army Corps, which included the East Prussian regiments and whose headquarters were located in Königsberg.

Later, the statue was moved to the Kneiphof Town Hall, and even later to the city history museum, where it stood safely until the summer of 1944. During the August bombing of Königsberg, the statue perished in a fire.

In Insterburg (Chernyakhovsk), a statue of Hindenburg was also erected near the Kreishaus (district administration). Remarkably, the Insterburg Hindenburg was a copy of a similar monument erected in Berlin, although much smaller in size. What happened to the sculpture after the First World War is unclear, but it is unlikely to have stood for very long, since no post-war references to it have been found.

In Angerburg (Węgorzewo, Poland) in the park near Kinderhilfe a sculpture of a medieval knight with the face of the same Hindenburg, an Iron Cross on his chest and a shield with an eagle in his hand was installed. His post-war fate is also unknown.

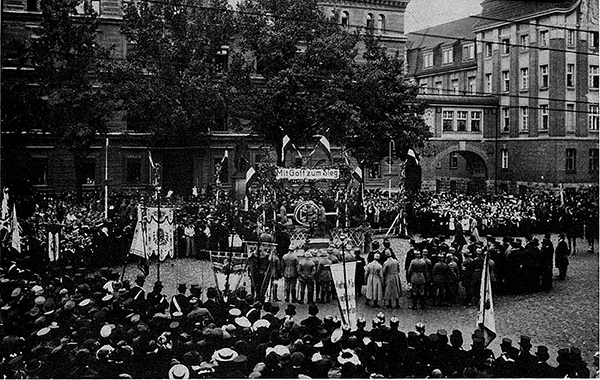

In Gumbinnen (Gusev), the so-called "Hindenburg plate" was installed on the square near the district government building. It was an image of the Iron Cross with the inscription "with God to victory" on top. Its ceremonial opening took place on October 2, 1915. The cost of the donation, as well as the nail, was 50 pfennigs.

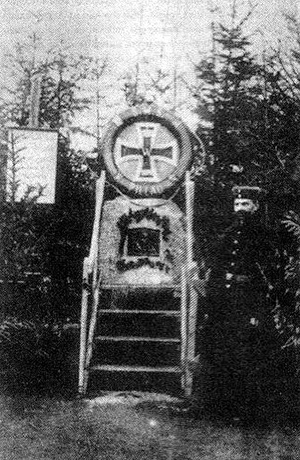

But in Pillau (Baltiysk) a wooden lifebuoy was installed, into which anyone could hammer silver or gold nails. By the end of 1915, 28 gold nails were hammered into the monument, on which the names of the deceased residents of this city were engraved. After 1920, the lifebuoy with the name nails was moved to the town hall. Its further fate is unknown.

There was also a "Hindenburg plate" in Tilsit (Sovetsk). It was a wooden plate with an image of Hindenburg's face and allegorical images of the warrior and defender. It was not possible to find out where it was located, or what its post-war fate was.

In general, in addition to the "traditional" sculptures (knights, eagles, crosses, etc.), there were also some very exotic ones. For example, in some German cities, nails were driven into models of horses, owls, ravens, submarines, airplanes, cannons, machine guns, military maps, and even grenades.

The peak of popularity of the "iron soldiers" was in 1915-1916. Later, with the worsening situation at the front, with the impoverishment of the German population and the loss of faith in victory, there were fewer and fewer donors. The last known sculpture (the Iron Cross, erected in the Lower Saxon town of Aersen) dates back to January 1918.

The fate of those sculptures that remained unfinished was simple - they were disposed of without unnecessary publicity. Some finished sculptures, as mentioned above, ended up in museums. The bombing of German cities in 1944-1945, as well as military actions during World War II, led to the fact that most of the "iron soldiers" perished in fires. To date, there is information about 345 surviving objects.

Sources:

Gumbinnen — City and Land (2 groups), Bilddokumentation of unusual land parcels. — Bielefeld, 1985.

Dietlinde Munzel-Everling. Death sentences: Wehrmann in Eisen, Nagel-Roland, Eisernes Kreuz. — Wiesbaden, 2008

chernyahovsk.com/forum/

forum.kenig.org

Bildarchive