Internal services of the Marienburg Castle

Management of the economy and utility rooms

The administration of Marienburg can be divided into lower and higher offices/services. Among the lower offices are the units responsible for the economy (also called household services), such as the caravanserai, temple master, kitchen master, bakery master, mill master, etc. (described in detail below). The higher offices (Supreme Master, Grand Komtur and Treasurer) are not discussed here. In terms of time, we will limit ourselves to the period of the Supreme Master's stay in Marienburg from 1309-1457, especially the period around 1400, since this is the best covered in the sources.

Three questions will be considered:

1. What lower services existed in Marienburg and where might they have been

located?

2. Who occupied them? Were there opportunities for promotion?

3. Can fundamental differences be found between the services of the Marienburg

convent and those of other castles of the Teutonic Order?

Publications and research situation

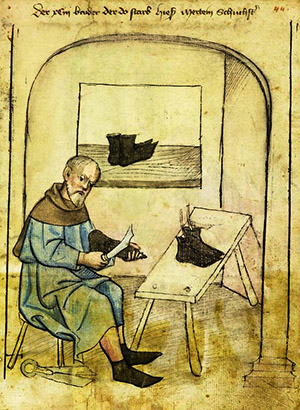

If we look at the history of Marienburg from an economic point of view and at the localized internal services, it becomes clear that the main business and accounting books for the central house of the Order around 1400 were published a very long time ago (about a century ago): these include the "Book of the Marienburg Treasurer 1399-1409" (Marienburger Tresslerbuch, hereinafter MTV) edited by Erich Joachim, the "Chinsch Book of the House of Marienburg 1410-1412" (Zinsbuch des Hauses Marienburg, hereinafter ZHM), the "Expense Book of the Marienburg Housekomturs 1410-1420" (Ausgabebuch des Marienburger Hauskomtur, hereinafter AMN), the "Book of the Marienburg Convent 1399-1412" (Marienburger Konventsbuch, MKV) and "Marienburg Office Ledger" (Marienburger Ämterbuch, hereinafter MAV) - the last four edited by Walter Ziesemer.

Two more books that fit the period and subject matter can be added to the list: the Great Tax Book 1414-1438 (Grosse Zinsbuch, hereinafter GZB) and the Great Office Book (Grosse Ämterbuch, hereinafter GAB). The first was edited by Peter Thielen, the second by the same Walter Ziesemer. — A.K.

The research situation can be described as good: it is possible to obtain basic knowledge about the order and everyday life in Marienburg, about the great administrators (Magistr, Grand Komtur and Treasurer), as well as about the economic management and lower services in Marienburg. However, it should be noted that more modern literature on the lower services is mainly available only in Polish, so this contribution is to some extent a translation of Polish studies into German.

In the footnotes, the author provides a large list of works on the topic, which it does not seem necessary to cite here, and some of them are given in the list of sources and literature. — A.K.

Basic functioning of lower services

Unfortunately, the total number of Order brothers for the castle of Marienburg is unknown. Their number can of course be compared with the convent of Elbing, which in its heyday had about 50 brothers (Ziesemer, S.82; Semrau, S.48). The convent of Königsberg was also quite large (1422 – 68 brothers) and can be used as a comparison (Vercamer, S.77). It is estimated that there were about 80 brothers in Marienburg – thus, several hundred people must have been in the castle itself (Jähnig, S.134).

If we turn to the lower services, we must distinguish between the external and internal services (inside the castle). The external positions in the Marienburg Commandery were occupied by brothers who were considered members of the main house, but mostly sat in their regional places outside the castle.

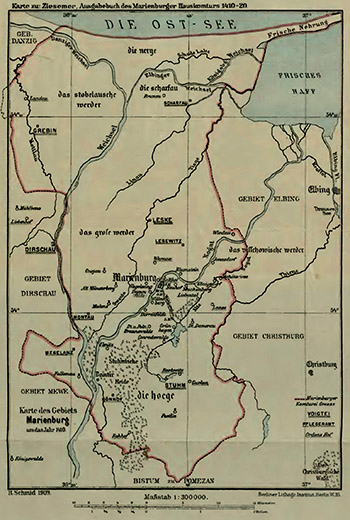

Of these, the following should be mentioned, as they are listed in the Marienburg Account Book (MAB, S.10-92; Sielmann, S.6-7):

— in Grosser Werder*: Vogt and Horse Marshal in Leske, as well as the Pflegers

of Lesewitz and Montau.

— at the mouth of the Vistula: the fish master in Scharfau

— on the left bank of the Vistula at Stublauischer Werder: Vogt of Grebin

— on the high ground (the area near Marienburg in the Stum area): Vogt of Stum

— the forester in Bönhof (Rechhofer Forst in later, German

times )

— a small administration of the Pfleger of Mösland (already in Pomerania).

As Arthur Sielmann noted in 1921 (Sielmann, p. 8), they were listed in the Marienburg Account Book with far fewer gaps than the actual house internal services, which will be discussed below. This may be due to the financial independence of the house services (in contrast to the external services). The house administrations in the castle usually received their maintenance money from three sources: either from the treasurer, or from the house commander/house commander, or from their own income (through the sale of surpluses). Therefore, the treasurer with his coffers is only briefly mentioned. This great steward was in charge of two (actually three) coffers: the coffers of the Supreme Master (also called the "sovereign") and the coffers of the Marienburg convent. In addition, there was also a debt coffers, but it plays no role here (Klein, p. 90-92; Sarnowsky, p. 54).

From the second treasury, the conventual treasury, the housecomtur, who did not have his own treasury, received his annual budget from the treasurer. From this he had to maintain the house and distribute the money among the house services. It is also clear that payments to other house services (in addition to the housecomtur) were made from the monastery treasury: the kitchen master, the cellar keeper, the quartermaster, the master carpenter, the blacksmith, the millmaster, the cattle master, the stone master, the cart master and the horse marshal received money independently. Therefore, most of these positions had to have their own small treasury, independent of the housecomtur (Sielmann, p. 77). Their owners had to return the surplus to the treasurer only upon the transfer of the position, and they also issued invoices with his help. Ziesemer has already established that the payments from the treasurer to these treasuries were mainly fixed, stable, as evidenced by the constant expenses for these positions. It is easy to see a recurring pattern: from 1399 to 1410, the kitchen master received 80 marks per year for the purchase of oxen (Ziesemer, S. XVIII/MKB). After 1410, the master baker, blacksmith and carver usually received around 40 marks per year from the housekomtur in four installments for the wages of servants (AMH, S.14, 43–45, 87–90, 120–21, 133, 159–61, 205–06, 263, 296, 323, 344). The caravanserai received large sums (around 350 marks), but there are no records of their use at the time (AMH, S. 44, 88, 133–34, 206–07, 264, 297, 324, 345, 1412–20). The horse marshal received around 50 marks for hay, the shoemaker several times 33 marks per month, the cellar master received around 65 marks from the treasurer in 1400 for the procurement of barley for the malthouse, and the trapper 26 marks for the production of 45 sheets of “grey cloth” (Sarnowsky, S. 168). Other services, such as the grain master or the head of the kitchen, received funds exclusively from the housekomtur and made settlements with him (Thielen, S. 112). The division of responsibility for expenses between the treasurer and the house manager is not entirely clear.

On the other hand, the profits from the services went directly to the conventual treasury (i.e. to the treasurer). Incidentally, they are insignificant: around 1400, the conventual treasury received an average of about 8,000-8,500 marks (see Fig. 1). Most of these funds came from the revenues of the tax-paying villages that were part of the Marienburg commandery. Only about 300 marks were contributed by the house services (excluding the trade of the Great Scheffer). For example, a garden master can be estimated to have paid about 20 marks per year (MKB, pp. 28, 61, 189, 198). A millmaster had to pay 50 marks from the fulling mill and about 34 marks from the sale of malt (MKB, pp. 29, 61, 83, 114, 141). In the "good years" (before 1410) the expenses of the convent were clearly lower than the income (around 2000-5000 m.). For example, the hauskomtur received 2900 marks in 1395 and 2328 marks in 1407 (Sielmann, p.66). From these amounts, it covered the majority of the expenses.

What lower services existed in Marienburg? Did they change over time?

At this stage, it is time to figure out what internal services we are talking about. In total, there are 23 economic services and positions in the castle :

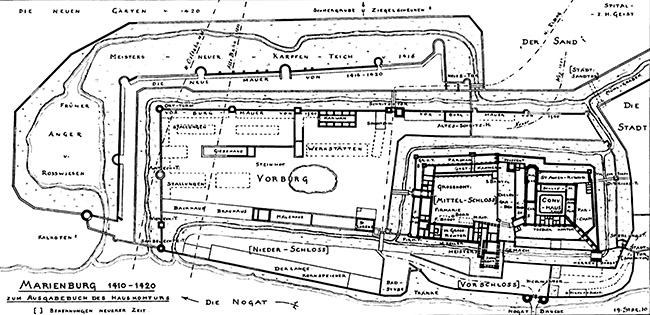

In the High Castle:

- House Commandant/House Commandant - a top-level manager; directly responsible for the harness workshop

- Bell Maker - All activities related to the churches of the convent

- Kitchen Master, Bakeries and Cellars - Supplying the Convent

- Gatekeeper/Gatekeeper - Oversees the main gate (high and middle castle)

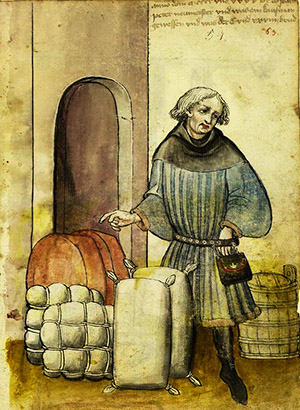

- Intendant - clothing; supplying the castle with fabrics

On the foreburg:

- Horse Marshals and Grain Masters - Horses and Grain Delivery

- Master blacksmith, master shoemaker and toolmaker - production of various products

- Caravan Manager - horse-drawn and mobile transport; military property and equipment; timber supply for the convent

- Master Wood Carver - Wooden Weapons (Crossbow, Arrows, Shafts, etc.)

- Livestock Breeder and Gardener - Livestock and gardens of the order; care of old servants

- Almshouse Manager - Hospital/Care for Elderly Brothers/Servants

- The Grand Scheffer is the organization of the Order's foreign trade

- Millmaster - oversees the Order's mills

- Woodworker - responsible for woodworking

- Housekeeping Manager - Managing Large Kitchen Supplies

- Stone Master - responsible for the production of bricks, etc.

- Mason - responsible for masonry construction projects and repairs

From what point can these internal services in Marienburg be identified? In the first half of the 14th century, it is hardly possible to say anything about the castle services, since only a few names with the designation of their services are mentioned in the documents. The "Marienburg account book" begins for most services around the 1380s. However, this does not mean that such services did not exist earlier (Józwiak/Trupinda, S.411-413). In any case, the gap in the account book for the years 1392-1400 (under the Grand Masters Konrad von Wallenrode and Konrad von Jungingen) for most internal services is striking, and should only be mentioned here in passing (Sielmann, S.48). It is impossible to explain exactly what this was connected with: an attempt to centralize the accounts (in this case, the centralized accounts were lost)? In any case, the Marienburg Office Book makes one thing clear: there was no centralized office, as was presented in other commandments, through which the transfer of authority to the successor took place according to the count (impressively documented in the GAB). In total, there are 31 offices listed (with the Grand Commander, the Treasurer and the offices in the outer courts), the heads of which drew up inventories for themselves when handing over the office.

The 23 services and positions in Marienburg and its environs can be divided hierarchically and geographically into:

(1) a managerial position;

(2) positions held in a high or middle castle;

(3) positions held in the forburgs.

1. The House Commander (cleine commendür; Latin vicepreceptor) was responsible for all organizational and internal administrative issues of the Marienburg convent, especially since there was no local commander at the headquarters of the order, since the Supreme Master had lived there since 1309 (Sielmann, S.22).

According to the statute, the junior positions in the castle were directly subordinate to the hauskomtur, as were the craftsmen and workers in the castle and on the castle grounds (Perlbach, S.108-9), although we have already seen that some positions actually had an independent treasury and were apparently hardly accountable to the hauskomtur, since they conducted their settlements with the treasurer. On the other hand, the hauskomtur could also replace the treasurer in case of temporary absence (Ziesemer, S.VIII/AMH). In case of illness or absence of the hauskomtur, he, in turn, was replaced by the treasurer, the cellar master/cup-keeper or the cattleman (AMH, S. 197–198; 201; 204–207, 210, 217, 256, 324). Here again we see close cooperation, which, however, sometimes makes it difficult to perceive a clear delineation of authority. The Hauskomtur was also responsible for the gardens, wagons and draft animals; he sent large deliveries of materials and goods to the departments subordinate to him (Sarnowsky, S. 136). The Hauskomtur even had a limited involvement in trade, as evidenced by the fish sales by the Hauskomtur of Thorn and the Prussian March (GStPK Berlin, XX. HA, OBA 11711, vgl. JH I/1; Sarnowsky, S. 142). In addition to his higher tasks, the Hauskomtur had special responsibility for the saddlery in the castle. In the first half of the 15th century, he alternated this position with that of master shoemaker at least once: in 1436, he handed over responsibility for the saddlery to the shoemaker Hans Schunemann. However, in 1437, the shoemaker returned it to the Hauskomtur (MAB, S. 6-10). His jurisdiction also extended to the town of Marienburg (Thielen, S. 104; Długokecki, S. 62). All current affairs related to the castle were managed from his treasury, be it construction work, wages for workers and artisans, transport, or the staff of the Grand Master. Obviously, this often concerned small matters: replacing a castle here, renewing a fence there, replenishing food supplies for the Master’s kitchen here, paying workers to repair a roof (AMH). Thus, while the treasurer was responsible for large annual budgets, the hauskomtur made up for the shortfall in financial resources in the treasury. Official reports from the 15th century also clearly show that the hauskomtur was responsible for paying the artisans (e.g. the moulder) and tradesmen (e.g. the fishmonger) who belonged to the castle (AMH, S. 36, 116, 192).

He was also apparently responsible for the Prussian vitings and guards (AMH, S.75, 79, 107, 109; Józwiak/Trupinda, S.414). The donations he paid at Christmas (to the secular service class) also appear several times (AMH, S.194, 243, 287, 337, 361). Sometimes it can be determined that the housecomtur did not know exactly what the relevant official spent the money on when he covered the expenses of another department. He then made a note: a separate entry will be made (AMH, S.7, 8, 90). In this way, the official provided a justification later. The housecomtur also often supplied the master with food products, such as all kinds of poultry, fresh fish, crayfish, eggs, fruits, vegetables of various kinds, etc. All of this was paid for from the convent treasury. The Hauskomtur was also responsible for the equipment for the master's kitchen; there was no clear separation from the convent (AMH, S.28, 35, 39, 83, 84). However, no expenses related to the supply of grain, flour or bread have been found; the grain and baking master was obviously directly responsible for this. Meat and sausage products did not pass through the Hauskomtur either (Sielmann, S.10). With the completion of the main construction work on the castle, it is also noticeable that at the beginning of the 15th century, masons and carpenters stopped working in the castle, and their official duties were taken over by the Hauskomtur (Sielmann, S.32). His residence, in accordance with his central importance, was located in the high castle next to the treasurer, in the area of the Stamp Tower/Pfaffenturm (Herrmann, S.261-294).

2. The positions that can be assigned to a convent in a high castle are: bell master, cellar master, gate master, kitchen master, baker's master, quartermaster.

Let us briefly describe their areas of responsibility.

The bell master was responsible for the church vessels in the churches and chapels on the castle grounds – St. Mary’s Church, St. Anne’s Chapel, St. Lawrence’s Church, St. Bartholomew’s Chapel – there were seven churches and chapels in the castle grounds in total (Długokęcki, p.66). At the end of the 14th century, the Marienburg Account Book provides us with more information about his activities: he was the custodian of the church vessels , in particular of St. Mary’s Church and the four adjoining sacristies. One of the sacristies was also named after him: in dez glockmeisters sacristien. His expenses on gold and silver vessels, by the way, were under the control of the master’s treasury, while ordinary expenses, as in other departments, were regulated by the hauskomtur. The bell maker was also in charge of the castle library: 41 Latin and 12 German books are mentioned in it (Mentzel-Reuters, S.246-61). He was also responsible for the bell itself and its punctual ringing, which called the brothers to prayer and to perform their duties (Perlbach, S.147). In a document from 8 November 1343, which he witnessed, the bell maker is called a sacristan (PrUB 3.618). Thus, it seems that in most cases he was a cleric . There are many reasons to assume that he lived in the immediate vicinity of the Church of the Virgin Mary, possibly in the Stamp Tower, but there is no definitive certainty about this (Józwiak/Trupinda, S.430).

The intendant was responsible not only for the equipment and clothing of the Order's brothers and other castle servants, but also for supplying the castle itself with fabrics, such as for blankets, curtains, coats of arms, etc. (Józwiak/Trupinda, S. 444). It can be assumed, along with Józwiak/Trupinda, that the intendant temporarily managed the tanner's yard, which remains open due to the ambiguity of the original passage - "8 cattle ** were paid for sawing boards by the intendant in the tanner's yard" (AMH, S. 350). The tanner's yard was located in the foreburg. The intendant's main activity - sewing clothes, which he carried out together with his subordinate tailors - must have been carried out in a specially equipped workshop (AMH, S. 211, 216). However, it is unclear where this workshop was located. The intendant himself most likely lived in the high castle, although he was a grey cloak (brother sariant). The intendant's service in Marienburg was also temporarily under the control of the Great Schäfer (Thielen, S.109).

The cellar master , kitchen master and baker worked closely together, which is why they were all housed in the high castle. In addition to the large, partly two-storey cellars in the high castle (in the northern and eastern parts, which had existed since 1396), the cellar master also had to look after the brewery and malt house, as well as the cooperage ( documented since 1432 ) in the forburg (near the church of St. Lawrence). Various types of beer were brewed in the castle: Märzbier, Collacienbier, Konventsbier, Speisebier and also mead. The cellar master also had the appropriate cups, jugs and cauldrons made of silver, tin, steel, brass and copper (MAB, S.92-7). Here we can clearly see the cooperation between the departments, which was carried out only indirectly through the hauskomtur: for example, the cellar keeper received the raw materials for brewing beer from the gardener, honey from the honey taxes, barley from the grain master , malt from the master miller , and he had to prepare firewood himself (for which he received money from the hauskomtur ). In the cellar alone, he had three servants at his disposal (AMN, S.256, 288-90, 317-19). The mentioned services (brewery, malthouse and cooperage) were most likely to be located in the forburg near the Church of St. Lawrence (Józwiak/Trupinda, S.431).

The kitchen master was responsible for the slaughterhouse , oxen stable, pigsty and mustard mill (AMH, S.15, 20, 25, 138, 172, 211, 294; MAB, S.136, 138; MKB S.85), all of which were located in the forenburg, although their exact location cannot be determined (Józwiak/Trupinda, S.441). The kitchen master himself was located next to his kitchen, which was located on the ground floor of the west wing of the high castle. The Grand Master had his own separate kitchen, but the Marienburg Account Book does not mention a second kitchen master. It can therefore be assumed that the Grand Master's kitchen was managed by cooks reporting to the kitchen master. To supply the convent, food and kitchen utensils were required, which were listed in each shift of the kitchen master (MAV, S.136-9). As an example of the amount of kitchen utensils, one can mention 33 cauldrons, 28 pots, 5 grates, 8 iron skewers, 6 frying pans, 6 baking trays, 13 new pots, 13 new cauldrons (MAV, S.136-9). It is known that in 1416-20 the kitchen master also held the position of head of the kitchen economy (Sielmann, S.35). The tempil is a larger warehouse in which the kitchen utensils were stored, since the kitchen was too small for this purpose. The tempil was located in the center of the forburg. In the case of the kitchen, the cooperation between the services can also be traced in the sources: on the one hand, taxes in kind from the surrounding villages went directly to the kitchen, on the other hand, individual economic units (cattleman, gardener, head shepherd) also supplied the kitchen with everything it needed. Honey, in turn, came from the commandries of Tuchel and Schlochau (Sielmann, p. 86). For its part, the kitchen passed on materials such as furs or bones to the quartermaster or master carver.

The position of the bakery master can be ignored here, his task is clearly defined – only in this: he was directly assigned the mill, which operated independently of the mills of the master miller (Józwiak/Trupinda, S.443). Previously, it was assumed that his place was in the foreburg, but some evidence indicates that the bakery was located directly in the high castle in the southern wing, next to the kitchen (Józwiak/Trupinda, S.443).

The gatekeepers – among them the senior and junior gatekeepers (AMN; Józwiak/Trupinda, S.434) – had to watch over the two largest gates, one to the high castle, the other to the middle castle, and ensure their maintenance. It can be assumed that they also had their own quarters near the gates (Józwiak/Trupinda, S.436-7).

3. This brings us to the economic services that were located in the foreburg, since they usually required extensive workrooms or barns/stables. While the Convent House and the Middle Castle (the residence of the Master) were the most important parts of the Marienburg functionally and architecturally, the extensive foreburg area (c. 130-145 x 270 m) to the north of them and along the Nogat was given over to workshops, stables and storage rooms (Torbus, S.285). The following positions can be mentioned in this area: caravan master, head shepherd, head gardener, grain master, mill master, mason, horse marshal, blacksmith, carver, shoemaker, almshouse, stonemason, kitchen master, cattle master, carpenter.

The office of the Grand Schäffer will be mentioned here only briefly (Sarnowsky/Link, S.1-26). Although it is classified as a domestic office, the Grand Schäffer of Marienburg performed a role that over the centuries extended far beyond the region through the export and import of goods (especially grain and cloth), thereby bringing in thousands of marks for the Order. It is actually surprising that his office did not occupy a high position in the hierarchy of the Order. This may have something to do with the tradition of the office; the statutes of the Teutonic Order state that the Grand Master must take with him two brother knights as companions and one brother sariant as a "scheffere" (Perlbach, S.99; Sarnowsky, S.88-99). This probably refers to the brother who was entrusted with financial affairs, but who had not yet taken over the management of the Order's trade. Due to his numerous travels, the Grand Schäfer was practically destined to carry out special assignments for the Grand Master and the convent, such as purchasing exotic fruits, spices, sugar, etc. Imported products were also purchased separately for various services: for example, fabrics for the quartermaster, iron for the blacksmiths, etc. (Sarnowsky, p. 96). The Grand Schäfer made settlements with the Grand Komtur and the treasurer once a year (Sarnowsky, p. 89). Unfortunately, the location of his premises in Marienburg is unknown - at least there is no indication of this in his account books (Jähnig, p. 138).

The caravanserai held one of the most important positions in the castle: the caravanserai (built around 1300–1340, today well restored and used as a conference centre) was the equivalent of an armoury or modern “arsenal”: military equipment, transport and road vehicles were stored here. It included large areas with workshops, where, for example, wheels were made; directly north of the castle was the Neuhof manor. It also (temporarily) had its own stud farm with the Order’s farm Kalthof near Marienburg. The caravanserai also had a second task: to supply the castle with firewood. For this purpose, he had a plot of land (Holzhof) on the Nogat, the location of which is unfortunately impossible. However, based on archaeological research, it seems at least highly probable that the official himself had his own home in the caravan itself (Józwiak/Trupinda, S.455-56). Several sources indicate that other small outbuildings and barns were erected around the caravan. Gardeners from the surrounding villages of Damm and Vogelsang were also available to him as workers (Długokecki, S.62).

The shoemaker was responsible for the production and storage of all leather goods required by the castle. He was also responsible for the tanning store, the tannery mill and the craftsmen employed therein (Thielen, S.109). He was also responsible for the tannery house and workshop – at least until 1420, when there are (albeit ambiguous) indications that these responsibilities had passed to the intendant (AMH, S.350). However, supervision of the saddle house – which also dealt with the production of leather goods in a broader sense, and for which it can be assumed that the shoemaker was responsible – was entrusted to the hauskomtur. Various sources indicate that the workshops belonging to this service were located near the Sparrow Gate, later called the Shoe Gate (AMH, S.459), in the direction of the town of Marienburg.

In terms of horse breeding, Marienburg was an important place in the Order's state, so there were several horse marshals here . Not far from the castle were Kalthof and Sandhof, two important livestock farms with stables (MAV, S.97-101). When changing horse marshals, the different horse breeds were also listed (Jähnig, S.135). Each knight had to have three horses (a war horse, a road horse and a horse for a servant). The military importance of horses for the Teutonic Order in Prussia hardly needs mentioning - in the GZB the number of horses for the knight brothers is listed in addition to their equipment. There is also a horse register for the Marienburg command (MAV, S.154-8; Długokecki, S.63), in which almost all the animals are indeed listed by name in 1445. The stables of the Grand Master, Grand Komtur, Treasurer and Convent were located in the forburg. The Grand Marshals had their own horse marshals. The horse marshal of the Convent was in charge of the Gorke farm north of Marienburg, where there was a large herd of cattle, pigs and sheep. The other livestock farms were under the control of the master cattleman. The second horse marshal was at the Order farm of Leschke, not far from Marienburg (OVA, 8372, 8427; Thielen, S.108).

The grain master was responsible for the supply of grain and legumes to the monastery. The granaries were located in the high castle, in the chapel of St. Nicholas, St. Lawrence and in the malt house (in the western part of the forburg). The oldest list of storage facilities dates back to 1378 (MAB, p. 115; Benninghoven, p. 581). The grain came from the farm, in kind from the surrounding villages and from purchases. It was stored not only to meet the monastery’s basic needs, but also to create reserves for difficult times. The “Account Book of the Marienburg Hauskomtur” does not mention grain, flour or bread, so this area must have been served directly by the grain and baking masters (Sielmann, p. 10). The grain master also had to provide for the master’s residence and his stables, barns and granaries (AMH, S.46–7, 90, 122, 179, 180, 208, 233, 264–5). The four grain warehouses belonging to the grain master were distributed throughout the castle, but the master’s seat, according to some source fragments, was in the so-called Buttermilk Tower. At first, this building was apparently located directly on the Nogat and outside the enclosing wall of the second foreburg; later, it was included in the fortifications (Józwiak/Trupinda, S.458).

Although the master woodcarver was a greycoat in the 15th century, he may have been a full brother before that (AMH, S.129). In any case, he had three or four servants at his disposal at all times, and he hired bowmakers and shieldmakers as needed. Crossbows were also made in his workshops. The accounts of the Great Scheffer clearly show that he supplied the master woodcarver directly with raw materials (Sarnowsky/Link, S.340). The localization is difficult: the sources often refer to the "alde snicyhus"/old carver's house. Therefore, in the past, the woodcarver's house was often equated with it - it is located to the east of the middle castle outside the moat, but within the wall surrounding the forburg. Apparently, this was the site of the old woodcarver's house, which served as accommodation for foreign guests from the early 15th century onwards. The new house of the woodcarver must have been located elsewhere: in 1414 there is a reference to “at the carved gate” (AMH, S.147), which nevertheless indicates that the new building was located here, but this is only an assumption (Józwiak/Trupinda, S.471). Various workshops belonged to this service and were distributed throughout the forburg: thus in the Church of St. Lawrence the arrows were stored on the roof, and in Steinhof.

In addition to cattle, pigs and sheep, the master herdsman also had to oversee a large number of foodstuffs and their production/processing. For example, inventories mention butter, cheese and meat, which were apparently produced under his supervision. Also mentioned are large quantities of barley and oats for cattle feed (the so-called barley rent of 3,100 sheffels, from villages and inns located in Gross Werder ). At his disposal were a chamberlain, a master shepherd and servants (incidentally, female workers are also mentioned here). The herdsman and his various outbuildings were located in the foreburg. The barns (we are talking about several thousand animals) were probably not located in one place in the foreburg, but the herdsman’s residence – as the sources indicate – may have been in the middle of the eastern part of the foreburg (Józwiak/Trupinda, p.477; Długokecki, p.62). From 1417 until the end of the Order's rule he managed the Kalthof farm.

The master gardener looked after the herb garden and the fruit trees; he also had a winegrower under his command. He was responsible for the staff of servants who looked after the beds of medicinal plants in the herb garden, which was located in the forenburg next to the Church of St. Lawrence (MAB, S.147). He managed his own small farm, the harvest of which annually brought in 20 marks to the treasury of the convent (OVA, 1458). He also supervised the malt growing in the Liebenthal next to the castle. Since the master gardener was responsible for the infirmary in the Church of St. Lawrence, he was probably located there until 1446. However, he probably had a second location, which may have been located in front of the eastern defensive walls of the forenburg (Józwiak/Trupinda, S.477).

The almshouse manager/hospitalier was in charge of the 80-bed Hospital of the Holy Spirit (Heilig-Geist-Spital), which was, however, not comparable in size to the hospital in Elbing (MAB, S.116-120). The master's firmary, intended for the brothers of the Order, was located in the middle castle. To support his duties, the hospitalier had his own treasury, for which he was also entitled to a farm in Willenberg. Presumably, the hospitalier had his own room - dem spittler czu siner kamer - but it is not known where it might have been (AMN, S.113; Józwiak/Trupinda, S.486).

Master miller. The construction of mills was only permitted with the permission of the order (mill regalia). Mills located away from the order castles were often rented out, which was very profitable for the order (Steffen, S.73-92), since millers paid very high taxes for the use of the mill. However, each commandery also had its own mills, which were managed by mill masters. The miller had to pay for the workers and for repairs (especially the replacement of millstones). Under his management, bread was also baked from rye and wheat, which was necessary to supply the convent. The Book of the Marienburg Convent shows that the costs could vary from year to year depending on needs: for example, in one year (1401) the master miller paid 115 marks 4 cattle for shafts, wood, millstones, a dug canal and a barn, while in 1403 only 12.5 marks for canals and fortifications at the mill pond (MKV, S.62, 116-7; Sarnowsky, S.156). In total, around 1440, six order mills of Marienburg Castle are recorded - in addition to the mill in the mill yard, there were also the upper, middle and lower mills, as well as the village mill and the fulling mill (MAV, S.150; Długokecki, S.25-30). Thanks to the income from the subjects who used the mills, the millmaster was able to manage his farm well and pay the monastery treasury 50 marks per mill and 30-35 marks per year for malt (Sarnowsky, S.157-9). In addition to the four mills located outside the castle, there are two more - a topchak mill and a horse-drawn mill. The first was located in the foreburg, and the second - by the bridge gate . Probably there was a third mill, which was located by the eastern wall of the foreburg. The millmaster had his own place - the mill yard. The mill yard must have been located within the foreburg, some evidence points to Rossmühle as its location, but there are still uncertainties (Józwiak/Trupinda, S.481).

A master carpenter is mentioned in the Marienburg Convent Book from 1399 to 1403 and between 1406 and 1412, but by 1410 this office had ceased to exist (MKB, S.31, 61, 85-6, 116, 257-9; Józwiak/Trupinda, S.482), presumably due to the decline in building activity in Marienburg. In any case, the official duties were taken over by the Hauskomtur (see above). The relevant sources mention a carpenter's yard in the forburg, but its exact location cannot be determined (Józwiak/Trupinda, S.483).

The kitchen manager (tempil) and his office have already been mentioned above (see the section “Kitchen Master”).

The stone master's office produced bricks, lime, mortar, and cannonballs for guns and cannons (Sielmann, p. 30). However, this office ceased to exist after the completion of the complex, similar to the carpenter described above (Schmid, p. 15). According to Sielmann, the stone master was the immediate assistant of the Grand Komtur, who was responsible for purchasing in the arsenal administration (Sielmann, p. 23). In this office, one can distinguish a saddler, a brick maker, and a stone sawyer, who supervised the workers. The stone master can be traced from 1343 to 1403, after which he can no longer be identified. From 1404 onwards, only the "stone office" is listed - the workers of the stone yard and the lime crushers were then paid directly by the housekomtur (Sielmann, p. 31). Who exactly managed the stone service later remains unclear: older literature claims that it was the hauskomtur; Józwiak and Trupinda contradict this and refer to the kemerer or steynkemerer, who was no longer a brother at that time, which indicates the professionalization of this position (Józwiak/Trupinda, S.460). About the location: in 2001–2004, archaeological excavations were carried out in the north-eastern part of the second foreburg, which resulted in the discovery of a large complex (18 x 56 meters), on the territory of which two large workshops were found (running from north to south), as well as several outbuildings, which were interpreted as a stone courtyard (Dabrowska, S.308). The sources also confirm the location of the courtyard in the foreburg (Józwiak/Trupinda, S.462). This courtyard operated in Marienburg until the end of the Order period.

The bricklayer , as the last service , worked closely with the stonemason. Here were listed the costs of using bricks and mortar in the construction of new buildings, as well as for repairing walls (Sielmann, p.30). Unfortunately, nothing can be said about its localization.

How were the services staffed ? Were there opportunities for promotion to higher positions?

The appointment of employees of the internal services and administrations was the exclusive competence of the Grand Master. Whether they were filled by brothers or grey cloaks, of course, depended on the status of the office. Bernhard Jähnig established for the Danzig Komturstvo that the offices of quartermaster, kitchen master, carving master, shoemaker, bakery master and blacksmith were usually entrusted to grey monks/Sariant brothers (Jähnig, S.93-4). I was able to establish something similar for Königsberg (Grand Schäffer, quartermaster, carving master, shoemaker, blacksmith master, bakery master). For Marienburg, intendants, carvers, blacksmiths, shoemakers and bakers with sariant brothers as office-holders can be identified for 1445/1451 (OVA, 9029; Sarnowsky, S.756; Józwiak/Trupinda, S.450). Conversely, this means that the positions of cellar master, horse marshal, caravan master, mill master, grand sheffer, firmari manager and some others were considered higher in rank, since they were occupied by full brothers. The distinction between grey cloaks and full brothers was, but only marginally, regulated by the statute: sariant brothers were allowed to own a maximum of two horses; they were often even more destitute (sometimes they had no horse at all). Unlike the full brothers, who came from the empire, they usually came from the nearby region – the sons of the townspeople and lower nobility (Vercamer, S.78; Militzer, S.73; Sielmann, S.81-2).

In order to assess the chances of promotion for the Marienburg Komturstvo, we need a representative number of service heads who can be verified by their names. Fortunately, the Marienburg Office Book lists all internal positions and describes the changes in positions over a certain period (mostly in the decades before and after 1400). The titles of positions are usually listed with the family name/first name/patronymic of the officials. If the family name was mentioned, I have included it here (see Appendix 1: Later Careers of Marienburg Officials) and compared it with existing contemporary position registers of Johann Voigt, Peter Thielen, Bernhard Jänig and Dieter Heckmann to determine whether these officials subsequently achieved higher positions (Voigt; Jähnig; Heckmann; Thielen). Research suggests that positions in the internal services usually did not offer many opportunities for promotion (Jähnig, p.94). This can clearly be refuted for the Marienburg area. What is true, and should be clearly emphasized, is the fact that the positions of the "gray cloaks" did not offer any opportunities for promotion. Not one of the holders of the positions in the carver's, blacksmith's and shoemaker's offices could be found again by me in the lists mentioned before or after the respective performance of duties. But at the same time the quartermaster and the baker are mentioned only by name, so it is impossible to follow them. The two names transmitted for the kitchen masters (Peter Schneidewinter and Hans Buntschuh) are also not included in the lists for higher positions. And it is worth noting that Hans Buntschuh (MAB, S.138-9) is repeatedly confirmed in the position over several years - it seems that he managed a good kitchen. Likewise, the grain masters, the bell master and the head of the kitchen economy do not rise.

In other services, however, one can observe astonishing careers (see Appendix 1). First, let us mention the Hauskomtur: Johann von Felde was Hauskomtur in 1386 and had already held the office of Komtur of Bütow in 1387–90. Heinrich Harder, his successor, was Hauskomtur in 1388, commandant of Rheden in 1390–91, and commandant of Nessau in 1391–02. Klaus Winterthur was Hauskomtur in 1398–00, but died in 1402. Johann Hochsliz was Hauskomtur in 1408 and already Landkomtur of the Ballei Etsch in 1409. Johann von Selbach became Hauskomtur in 1411 and from this position began a steep career, holding such posts as one of the great administrators - Grand Intendant in 1416, Commandant of Thorn (1414-16) and Brandenburg (1431-33). Nikolaus Görlitz is first mentioned as Kumpan of the Komtur of Balga (1415), and then he became Hauskomtur of Marienburg (1416-17). He then also had a steep career, becoming Grand Komtur in 1421, Grand Marshal in 1422 and Grand Intendant in 1422-28. The next Hauskomtur was Heinrich Hauer: first millmaster (1411), then Hauskomtur in Marienburg and immediately after that Vogt of Stum (1419-1422) and Komtur of Dirschau (1422-24?). However, there are also examples such as Heinrich von Podendorff, who was first Vogt of Stum (1404-11) and only then became Hauskomtur of Marienburg (1411-14) and was no longer installed by me after that. Nevertheless, this office already shows that in principle all possibilities for promotion were possible.

Among the Grand Schäfers, only Johann von Techwitz (1407 and 1410) has a career worth mentioning, as he later became Vogt of Grebin (1411). The other Grand Schäfers have not been identified by me in the respective lists before and after their accession to office. Among the equestrian marshals, the brothers of the order who later rose to the rank of Komtur can be distinguished: Georg von Seckendorff and Georg von Wenningen (two of four examples), while Nikolaus von Lubichau became Vogt of Soldau. Also worth mentioning is the career of Konrad Volkolt, who was equestrian marshal in 1390, Vogt of Stuhm in 1392-94, and can then be found again in positions in Marienburg (cellar master, cattleman, hospitaller). Johann von Felde, already mentioned as a Hauskomtur, is also interesting: after a career as Komtur of Bütow, he returns to Marienburg as a horse marshal. Here, it seems, it is assumed that he did not recommend himself for a higher career after all. Among the Hospitallers, two of the three brothers with clearly established surnames also became Komturs (Georg von Wirsberg, Peter von Lorch). Other positions are ambiguous: among the cellar keepers, six (out of 19) were promoted to the position of Vogt or Komtur. In the case of the mill masters, three (out of six) were promoted to the position of Vogt or Komtur.

In particular, in the case of the caravan wardens, five of the 12 representatives with family/first names were later promoted to higher positions (3 - komtur, 2 - vogts), and two more at least reached the position of hauskomtur (Johann von der Heyde, Heinrich von Rohwedel) in other castles. In the case of the herdsman, of the 14 officials, only two can be traced - the vogt and the komtur. Thus, this position obviously offered few opportunities for promotion.

A striking observation in these studies concerns the garden service, which included overseeing the order's gardens in Marienburg, as well as tending the servants' infirmary in the church of St. Lawrence. This position was apparently considered attractive to older men: of the five officials who can be identified, three (Georg von Seckendorff, Friedrich von Masbach, Wolf von Sausheim) held the position of gardener in Marienburg after extremely successful careers as commanders in Prussia.

Comparison with other commands

In Marienburg in particular, as well as in the commandries of Elbing and Königsberg, almost all economic and domestic services can be distinguished (Ziesemer, p. 81; Jähnig, p. 94-5); in other castles of the order, there were fewer economic institutions, depending on the size of the convent. Some of the positions (caravan master, blacksmith, saddle and shoemaker, carving master, kitchen or cellar master and quartermaster) follow from the rules and customs of the Teutonic Order and have analogues in other spiritual knightly orders (Sarnowsky, p. 163-4); some of them are also determined by temporal and regional circumstances (bridge master in Thorn, yarn master in Ragnit, stone master in Marienburg, coin master in Danzig).

Conclusion

In conclusion, some results can be noted:

1. The 23 internal services were mostly provided with their own treasury/funds and managed their affairs independently. Each service was responsible for a specific area or activity. They supported each other with contributions in kind, depending on the needs of the other services. The House Committee often intervened in daily affairs, allocating the necessary funds without fuss.

2. Most of the positions were held by full brothers. In principle, there were good opportunities for promotion to more prestigious positions (housemaster, caravan master, horse marshal, hospitaller, millmaster, cellar master), which can be proven in many cases.

3. In terms of structure and execution of official duties, Marienburg did not differ from other large convents (Elbing and Königsberg). However, it can be noted that the centralized accounting by the Komtur/Grand Administrators in other Komturstvos seems to have been clearly relaxed in Marienburg. This is certainly the result of the not entirely clear delineation of powers between the leading officials (Supreme Master, Treasurer, Housekomtur) in relation to house services.

_______________________

ANNEX 1

Further career path of officials of Marienburg Castle

Created according to the entries in the Marienburg office book, if officials were listed there by their last names. Those officials listed only by their first names have not been included here, as it is difficult to determine an earlier or later career path on this basis alone. All names found were checked against contemporary service directories compiled by Johannes Voigt, Peter G. Thielen, Bernhard Janig and Dieter Heckmann. These list all the "higher" services in Prussia and the ballets of the Holy Roman Empire. Other special registers (e.g. for the procurators of the order) as well as individual scattered prosopographical data could not be taken into account within the framework of this essay due to the abundance of names. Therefore, if the following list says "before/after not established", then this refers exclusively to the already mentioned Voigt/Thielen/Janig/Heckman registers, and it is quite possible that the names appear in other places as well. However, the main thing here is the general trend, namely how many lower-ranking officials subsequently reached the highest positions. This general trend can be summarized quite accurately by the following list and analyzed above in the main text.

House Committee:

- Johann von Felde - 1386 Hauskomtur; 1387-1390 Komtur of Bütow; 1392 Horse Marshal of Marienburg

- Heinrich Harde - 1388 Hauskomthur; 1390-91 Commander of Reden; 1391-1402 Commander of Nessau

- Claus Winterthur - 1398, 1400 Hauskomthur (+ 1402); before/after not established

- Johann Hochlitz (Hochslitz) - 1408 Hauskomthur; 1409 Landkomtour Balleya Etsh

- Johan Kintsberg (Künsberg) - 1408 Hauskomthur; before/after not established

- Johann von Selbach - 1411 Hauskomthur; 1411-1413 Vogt of Leipe [actually Komtur of Papau]; 1414-16 Commander of Thorn; 1416-22 Grand Intendant; 1422-31 commander of Mewe; 1431-33 Commander of Brandenburg

- Heinrich von Podendorff - 1404-11 Vogt of Stum; 1411-1414 housecomtur; after not installed

- Johann von Winterhausen - 1411-1414 cellar master; 1414-1416 house commander; after not established

- Nikolaus Görlitz - 1415 commander of Balga; 1416-17 Hauskomtur; 1417-18 Vogt of Grebin; 1421 Grand Commander; 1422 Grand Marshal; 1422-28 Grand Intendant and Commander of Christburg; 1432-? Commander of Reden; 1437/1441 Pfleger of Seehesten

- Heinrich Hauer - 1411 master miller; 1417-19 Hauskomtur; 1419-22 Vogt of Stum; 1422-24? Commander Dirschau

- Erwin Hugh von Heiligenberg - 1441 Hauskomthur; 1445-46 Commander Schlochau

- Johann von Birken - 1441 Hauskomthur; after not established

- Hans Melvis - 1446 Hauskomthur; after not established

- Konrat Zollner - 1448 Hauskomthur; after not established

Great Shepherd:

- Everhart von Virminen - 1376 The Great Scheffer

- Johann von Techwitz - 1407 and 1410 Grand Schäfer; 1409 Customs Administrator and 1411 Vogt of Grebin; after not established

- Johann von Dittenhof - 1408-1409 Grand Scheffer; before/after not established

- Friedrich Zorn - before/after not established

- Ludek Polzadt - 1410 Deputy of the Great Scheffer; 1411-1418 Great Scheffer; before/after not established

- Heinrich Seeburg - before/after not established

- Hans von Hirschbach - before/after not established

Horse Marshal:

- Berthold von Buchheim - 1381/87 Horse Marshal; before/after not established

- Berthold von Basse - 1383-87 Horse Marshal; before/after not established

- Kunzen Volkolt - 1390 Horse Marshal; 1392-1394 Vogt of Stum; 1397 Cellar Master; 1398 Master Cattleman; 1401 Hospitaller

- Johan von Velde - 1392 Horse Marshal (see House Command)

- Gottfried von Hozelt - 1392 Horse Marshal; before/after not established

- Hannos von Schowenburg - 1401 Horse Marshal; before/after not established

- Heiliger von der Stressen - 1402 Horse Marshal; before/after not established

- Georg von Seckendorff - 1412/1417 Horse Marshal; 1418-1420 Junior Master's Cumpan; 1420-21 Senior Master's Cumpan; 1421-23 Vogt of Grebin; 1423-24 Komtur of Schwetz; 1430 Gardener of Marienburg (presumably sent there due to old age)

- Nikolaus von Lubichau - 1412/1413 Horse Marshal; 1437 Vogt of Soldau; 1451 Gardener in Elbing

- Georg von Wenningen - 1417 Horse Marshal; before/after not established

- von Drauschwitz (Troschwitz) - 1430 horse marshal; 1433-34 junior kumpan 1434-35 senior kumpan of the master; 1436-42 commander of Gollub; 1442-47 bailiff of Brattian

Hospitaller:

- Conrad Volkolt - 1401 Hospitaller (see Horse Marshal)

- Berthold von Buheim - 1404 Hospitaller (see Horse Marshal)

- Peter von Waltenheim - 1406 Hospitaller; before/after not established

- Georg von Wirsberg - 1406 Hospitaller; 1408-1411 Grand Schäfer; 1411 Komtur of Rehden; 1422/27/28 Head of the Vitings in Ragnit; 1437 Kitchen Master, and also Mill Master in Königsberg (in Rehden he was commander for only a few months, perhaps he made a mistake there?)

- Nikolaus Froenacher - 1418 Hospitaller; before/after not established

- Peter von Lorsch - 1396 cellar master in Marienburg; 1415 bailiff of Dirschau; 1411 [?]-1416 commander of Mewe; 1415-16 bailiff of Roggenhausen; 1419/20 fish master in Putzig; 1420/24 Hospitaller

Kitchen Master:

- Peter Snidewinter - 1392 Kitchen Master; before/after not established

- Hans Buntschuh - 1399-1411 kitchen master; before/after not established

Cellar keeper:

- Peter von Lorsch - 1396 Cellar Master (see Hospitaller)

- Conrad Volkolt - 1397 Cellar Master (see Horse Marshal)

- Mates von Bibern - 1398 cellar keeper; before/after not established

- Peter von Stein - 1399 Cellar Master (see Bell Maker)

- Heinrich Leidensteten - until 1394 caretaker of the caravan; 1400 caretaker of the cellar; 1394-1403 pfleger of Meselanz

- Heinrich Kuchenmeister - 1400 Cellar Master (see Gardener)

- Heinrich Koppel - 1403 cellar keeper; before/after not established

- Lucas von Lichtenstein - 1411 cellar master; 1416 commander of Nessau; 1416-1419 commander of Ragnit; 1419, 1422-24, 1429-36 captain of Bütow; 1420 bailiff of Lauenburg; 1424-26 commander of Schönsee; 1437 captain of Lochstedt; 1440 amber master; 1445 captain of Tapiau

- Johann von Winterhausen - 1414 cellar keeper (see Hauskomtur)

- Klaus Filke - 1414 cellar keeper; before/after not established

- von Nussbeerg - 1415 cellar keeper; before/after not established

- Witsche von der Pforte - 1414 trade representative (liger) in Thorn; 1415 cellar master; before/after not established

- Rudolf Gross - 1419 cellar keeper; 1430 caravan keeper; after not established

- Heinrich von Trachenau - 1433 cellar keeper; before/after not established

- Wilhelm von Hundeborn - 1432 cellar master; 1444 junior master's chamberlain; 1444-45 senior master's chamberlain

- Kunz Gross - 1437 pfleger of Schaaken; 1445-1447 cellar keeper

- Ludwig von Holheim - 1447-48 cellar keeper; before/after not established

- Wilhelm von Künssberg - 1448-49 cellar keeper; before/after not established

- Conrad von Tiefen - 1449 cellar keeper; before/after not established

Grain Master:

- Hermann Hans - 1378 grain master; 1394 caravan keeper; 1394 kitchen manager

- Heinrich von Schönenberg - 1419 grain master; before/after not established

Mill Master:

- Heinrich Hauer - 1411 millmaster (see Hauskomtur)

- Hermann Oberstolz - 1420-1423 pfleger of Montau; 1430 millmaster

- Philipp von Kendenich - 1430 mill master; 1432-1435 commander of the ballet of Koblenz

- Friedrich von Schönenberg - 1441 millmaster; 1442/43 fishmaster from Draussen; after not established

- Johann von Buch - 1426/27 grain master of the command of Königsberg; 1435/37 pfleger of Neudenburg; 1441 mill master; 1446/47 bailiff of Stum

- Hans Schmedinger - 1454 millmaster; before/after not established

Master Gardener (looks like a "retirement position"):

- Johann Grimrod (Grunrod) - 1410 gardener

- Heinrich Küchmeister - 1390-96; 1414/1416 master cattleman; 1417/18 gardener; 1420 Kumpan of the Commander of Elbing

- Jörg von Seckendorff - 1430 gardener; (see Horse Marshal); after not established

- Friedrich von Masbach - 1415-17 Komtur of Memel; 1417 Hauskomtur of Elbing; 1423-27 Pfleger of Insterburg; 1444 Gardener

- Wolf von Sausheim - 1416-21 commander of Reden; 1421-38 commander of Osterode; 1438-39 pfleger of Bütow; 1441 gardener

Master Cattleman:

- Heinrich Stange - until 1381 cattleman; before/after not established

- Heinrich Riemann - 1381 cattleman; before/after not set

- Heinrich Langenfel Heinrich - 1381 cattleman; before/after not set

- Johann von Königshain - 1394 head of the kitchen; 1396 cattleman; after not established

- Klaus Molemeister - 1396 cattleman; before/after not established

- Kunz Volkolt - 1398 cattleman (see Horse Marshal)

- Ulrich Jonsdorfer - 1401 cattleman; before/after not established

- Heinrich Küchmeister - 1390-96; 1414 cattleman (see Gardener)

- Franz von Eckersberg - 1414 cattleman; before/after not established

- Rudolf Flemming - 1416 cattleman; before/after not established

- Friedrich Elhard - 1419 cattleman; before/after not established

- Hans Motheneer - 1430 cattleman; before/after not established

- Siegfried the Greek - 1445 cattleman; 1447-49 pfleger of Rastenburg; 1449-50 commander of Gollub; after not established

- Albrecht von Zeutern - 1445 cattleman; before/after not established

Caravan keeper:

- Heinrich von Leidenstäten - until 1394, caravan keeper (see Cellar keeper)

- Herman Hans - 1394 Caravan Master (see Grain Master)

- Bertus von Losin - 1396-1401 caravan keeper; before/after not established

- Johann von Wildenow - 1401 caravan keeper; before/after not established

- Conrad von Helmsdorf - 1405/1413 caravan keeper; 1417 pfleger of Meselanz; 1419-1427 pfleger of Montau; 1427-32 pfleger of Lesewitz

- Heinrich Poster - 1413-14 caravan keeper; 1422 mill master; 1422-25 commander of Althaus; 1429 mounted marshal of the commandery of Elbing

- Johann von Lintzenich - 1414; 1423 caravan keeper - after not established

- Gottfried von Geilenkirchen - 1416/20/21 Caravan keeper; 1437-38 Komtur of Schlochau; 1442 Pfleger of Montau

- Heinrich Ochs - 1418 pfleger of Labiau; 1422 caravan keeper; 1423-1426 pfleger of Gerdauen; 1431 fish master of the command of Königsberg

- Hans von Trachenau - 1423 caravan keeper; 1441 equestrian marshal of the command of Königsberg 1445-47 equestrian marshal of the command of Danzig

- Johann von der Heide - 1428 caravan keeper; 1431 hauskomtur of the command of Preussisch Mark; 1437/39 bell master in Marienburg

- Heinrich von Rowedel - 1428 caravan keeper; 1432/33 hauskomtur of Danzig

- Albrecht Kalb - 1430-1432 caravan keeper; 1446-1454 commander of Thorn

Bell Maker:

- Kunrad von Czaczcherney/Czaczcherney — 1394 bell maker; before/after not established

- Peter von Stein - 1398/1411 bell master (in 1399 he was a cellar master) - after that not established

- Engelhard von Nothafft - 1410 grain master; 1415 coin master; 1437 bell master; after not established

- Nikolaus von Sintchen - 1439/1441 bell maker; before/after not established

- Nikolaus Rohnenberg - 1441/44 bell maker; before/after not established

- Nikolaus von Brandenburg - 1444/48 bell maker; before/after not established

- Christian von Strosberg - 1448 Bell Master

Head of Kitchen Facilities:

- Hannus von Koenigshagen - 1394 Kitchen Superintendent (see Cattleman)

- Herman Hans - 1394 Kitchen Superintendent (see Grain Master)

- Johan von Dudelstad - 1398 kitchen manager; before/after not established

- Johan Lullen - 1398 Kitchen Superintendent; before/after not established

- Klaus Rude - 1399 Kitchen Superintendent; before/after not established

- Heinrich Küchmeister - 1416/1417 kitchen manager (see Gardener)

Master Carver:

- Hannus Tristam - 1409 engraver; before/after not established

- Hannus Anger - 1409 engraver; before/after not established

- Caspar von Conradswald - 1409 engraver; before/after not established

Master Blacksmith:

- Hannus von der Lobow - 1398 blacksmith; before/after not established

- Peter Numan - 1399 blacksmith; before/after not established

- Andreas Rohde - 1400/1402 blacksmith - before/after not established

Shoemaker:

- Peter von Langen Heinersdorf - 1397 shoemaker; before/after not established

- Niklaus Beschorn - 1392 shoemaker; before/after not established

- Peter Koching - 1400 shoemaker; before/after not established

- Peter Dene - 1409 shoemaker; before/after not established

- Nikolaus von Schellendorf - 1409 shoemaker - before/after not established

- Hans Schunemann - 1436 Shoemaker - before/after not established

Notes:

* Grosser Werder is a lowland located in the Vistula delta between the Vistula and the Nogat.

** Scot is a Prussian, as well as Polish (skoetz), monetary unit equal to 1/24 of a silver mark and 30/1 pfennig.

Sources and literature:

GStPK Berlin, XX. HA, OBA.

GStPK Berlin, XX. HA, OF.

Joachim E. The Marienburger Tresslerbuch of the Year 1399–1409. Königsberg, 1896.

Link C., Sarnowsky J. Studies and research of large-scale studies and obligations of German orders, Vol. 3: Large seaports in Marienburg. Cologne-Weimar-Wien 2008.

Perlbach M. The Statutes of German Orders. Halle, 1890.

Preussisches Urkundenbuch, Vol. 3, 1. Lfg. (1335–1341), hg. by Max Hein, Königsberg, 1944.

Thielen PG The gross volume of the German Ritterordens (1414-1438). N. G. Elwert, 1958

See also: W. Ausgabebuch of the Marienburg House of Economy from the years 1410-1420. Königsberg, 1911

Ziesemer W. The gross volume of German Orders. Danzig: Kafemann, 1921.

Ziesemer W. The Marienburger Book. Danzig, 1916.

Ziesemer W. The Marienburger Konventsbuch der Jahr 1399-1412. Danzig, 1913.

Ziesemer W. The Book of Marienburg Houses. Marienburg, 1910.

Benninghoven F. The city as a source of secondary socialist culture in the rich and poor German states // The city in the German language, Vol. 1, Sigmaringen, 1976, S. 565–601.

Dabrowska M. Badania Archaeological and architectural monuments on the remains of a small castle in Malbork dating from 1998–2004 // 15th session of the Pomorze Museum. Conference proceedings, November 30-02 December 2005, Elblag, 2005, pp. 303–315.

Długokecki W. Housekeeper and housekeepers in Marienburg in the early 15th century // Burgen kirchlicher bahusherrns. Munich-Berlin, 2001.

Heckmann D. Fighting the German Orders in Preußen and among the Chief Commanders of the Reichs until 1525. Torun, 2020.

Herrmann C. The Opera House at Marienburg: Reconstruction of the Functional Structures // Magister Opera. View of the Middle East Architecture of Europe, Festival for Death of Winterfell at 70th Anniversary. Regensburg, 2008.

Jähnig B. Organisation and cultural development of the German settlement in Marienburg // Development and research of the settlement, Hg. v. Peter Johanek, Sigmaringen, 1990, pp. 45–75.

Bernhart Jähnig, The List of Dignitaries and Officials of the Teutonic Order in Prussia // The Teutonic Order in Prussia and Livonia. The political and ecclesiastical structures of the 13th-16th centuries, Torun, 2015, pp. 291–345.

Józwiak S., Trupinda J. Organization of construction at the Krzyzacki castle in Malbork in the early 13th century. Malbork, 2011.

Klein A. The central financial management of the German Ordensstaat Preussen on the eve of the 15th anniversary. Leipzig, 1904.

Mentzel-Reuters A. Arma spiritualia. Books, books and literature in the German language. Wiesbaden, 2003.

Militzer K. From the Academy of Marienburg. Conversion, adoption and social structure of the German Orders 1190–1309. Marburg, 1999.

Sarnowsky J. The Conquest of the German Orders in Preussen (1382–1452). Cologne, 1993.

Semrau A. The Economic Plan of the Elbing Ordenhauses from the Year 1386 // Summary of the Copper Community 45 (1937), pp. 1–74.

Sielmann A. The Conversion of the Marienburg Haupthaus in the Time of 1400 // Journal of Western European Socialist Magazines 61 (1921), pp. 1–101.

Schmid B. Die Marienburg. Your friends. Würzburg 1955.

Steffen H. The Landmarks of Germany in the German Empire // Journal of Western European Socialist Republics 58 (1918), pp. 73–92.

Thielen PG The adoption of the Polish Ordensstaates. Cologne, 1965

Torbus T. The conventions in the Ordensland wars. Munich, 1998.

Verkamer G. Social studies and social modifications of the Konigsberg Communist Party in Poland (13.–16. January). Marburg, 2010.

Voigt J. Names of the German Order of Masters, Chief, Land Master, General Manager, Cabinet Maker, Voigt, Pfleger, Chief Executive Officer, Craftsman and Soldier Headmaster in Preussen. Königsberg, 1843.

Ziesemer W. Wirtschaftsordnung des Elbinger Ordenshauses // Sitzungsberichte der Altertumsgesellschaft Prussia 24 (1923), pp. 76–91.