Insterburg beer

The first beer in the lands captured by the German Order in Prussia was brewed in castle breweries for the brethren and servants. So the beer brewed in the brewery of the Insterburg castle marked the beginning of the history of the intoxicating drink, the taste of which was later appreciated not only by the people of Insterburg, but also by residents of other cities and countries.

The right to brew beer was granted to Insterburg by Elector Georg Wilhelm along with city rights. Before that, local residents received beer from the castle brewery, as well as from Königsberg, Wehlau and Friedland. Based on city law, each citizen, under certain conditions (read more about the right to brew beer in the city here), could brew 16 barrels of beer annually for a small tax (the Prussian beer barrel (German: Tonne) was 110 liters; it is easy to calculate that a little less than 1800 liters of beer could be brewed per year. — admin ).

In the middle of the 18th century, about one hundred Insterburg burghers had the right to brew beer.

Among the many types of beer brewed in the city, the most popular was “Insterburg Double Beer” (Insterburger Doppel Pils), which was also the strongest. The cost of beer was determined by the price of barley and changed every six months. If regular beer cost 7-9 pfennigs per shtof (Stof is a cup, a measure of liquid volume, approximately 1.15 liters; 96 shtofs made up a beer barrel. — admin ), then “Insterburg Double” cost twice as much.

The chronicler Lucanus gives the following description of the "Insterburg Double Beer": "It is the best drink to taste that can be found anywhere. The double beer "Cinnober" (German: cinnabar) is so strong and strong that if you heat it in a cup and set it on fire with paper, it will burn like vodka. Some drink it in small portions, as a medicine. It is sent in tons to Poland and other countries."

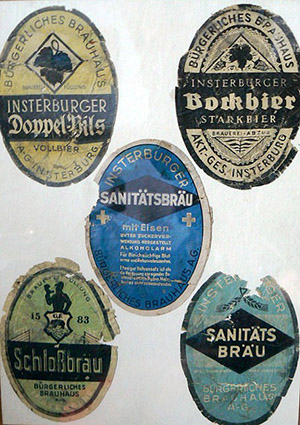

In addition to the Insterburg Double Beer, other varieties were also brewed. For example, there was the Sanitätsbräu variety – a medicinal beer containing iron, sweetened with refined sugar, with a low alcohol content for the sick, the anemic and those recovering. And, of course, the Castle Beer (Schloßbräu).

The high quality of Insterburg beer was determined by its excellent water. In a report compiled after examining the water in all German districts, the water in Insterburg was at the top of the list. According to the memoirs of the last director of the Insterburg City Brewery, Werner Bonow, the water was taken directly from the Angerapp River (now Angrapa). Naturally, the water was first filtered. Werner Bonow recalls that the high quality of the beer produced at his enterprise was based, in addition to the water, on a special method of processing the malt in his own malthouse. All phases of malting and brewing were constantly and carefully monitored by a modern laboratory.

At the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, there were three large brewing enterprises in Insterburg:

Deutsches Brauhaus Bruhn & Fröse ( German Brewery

Bruhn & Fröse on Ziegelstrasse (now Pobedy Street), later called the German

Brewery (Deutsches Braühaus , director

Wunderlich, head brewer Treutler). Over the years, the company existed under the

following names (by date of end of production/existence):

Braunbierbrauerei R. Fröse — 1865

German Braühaus Bruhn & Fröse – 1890

Braunbierbrauerei Heinrich Fröse — 1894

Braunbierbrauerei R. Fröses Söhne — 1908

Bürgerliches Brauhaus AG Abt. German Brauhaus Bruhn & Fröse – 1920

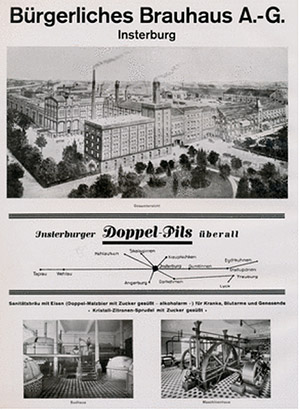

Bürgerliches Brauhaus F. A. Frisch (director Wilhelm Kalcher), on Schlossstrasse, behind the castle, next to the Brandes villa). At various times it bore the following names:

Bayerische Beerbrauerei FR Volkner — 1855

Bayerische Beerbrauerei Fr.A. Frisch - 1896

Bürgerliches Brauhaus AG vorm. F. A. Frisch — 1925

Bürgerliches Brauhaus AG – 1945

Böhmisches Brauhaus JH Bernecker (Bohemian Brewery of Bernecker, located on the steep bank of the Angerapp River).

Brewery of J. H. Bernecker — 1875

Böhmisches Brauhaus AG – 1896

According to the Insterburg address book for 1892, the brewery of the future "City Brewery" was founded in 1850. F.A. Frisch bought it in 1870 and rebuilt it for the production of Bavarian beer. The first brewing took place on April 15, 1876, and the first beer was sold on July 1 of the same year.

Until 1890, only two bottom-fermenting breweries operated in Insterburg. These were the Bürgerliches Brauhaus FA Frisch (Frisch City Brewery) and the Böhmisches Brauhaus (Bohemian Brewery). The other city breweries brewed the so-called top-fermenting "Braunbier" variety.

In 1885, both breweries produced 24,466 hectoliters of beer, in 1886 - 28,452 hl, in 1887 - 27,500 hl. In 1889, the annual beer production was 35,130 hl, and in 1890 already 41,100 hl. During the same period, the production of the four top-fermenting breweries remained unchanged and fluctuated between 10,000 and 11,000 hl.

In 1891, the Insterburg City Brewery produced 11,000 hl of beer, despite being the smallest brewery in the city. Some of the production was sold in bottles. That same year, thanks to the efforts of brewmaster Wilhelm Kalcher, the plant was modernized by the Chemnitz firm Burkhardt & Ziesler.

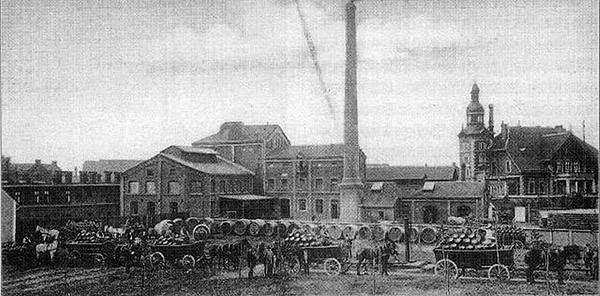

In 1896, the brewery became a joint-stock company under the name Bürgerliches Brauhaus AG with a share capital of 350,000 marks. Its director was the same Wilhelm Kalcher. The office was located at Belowstrasse 6 (during the Third Reich, the street was renamed Braureistrasse). The brewery was equipped with steam boilers.

If at the end of the 1890s beer production fluctuated at the level of 16,000-18,000 hl, then at the beginning of the 1900s it increased to 22,000-23,000 hl.

The brewery occupied an area of 23,950 square meters, of which 4,851 square meters were built up. The "city brewery" had warehouses in Gumbinnen (now Gusev), Ebenrode (Nesterov), Eidkau (Chernyshevskoye), Wehlau (Znamensk), Tapiau (Gvardeysk), Angerapp (Ozersk), Lieck (Elk), Treuburg (Oletsko), Skaisgirren (Bolshakovo) and other cities in East Prussia.

Before World War II, the City Brewery employed about 180 people. During the war, their number decreased significantly, although beer production continued.

At different times, there were various small breweries and enterprises in Insterburg: Insterburger Genossenschaftsbrauerei eGmbH, Braunbierbrauerei Fr. Techler, Bayrische Bierbrauerei C.Thomas, Braunbierbrauerei Rud. Stahr and others.

Ultimately, in 1917-1920, all the breweries were absorbed or annexed to the Insterburg City Brewery, under whose auspices and trademarks beers from other breweries were produced until 1945.

Insterburg Brewing in Memories

According to the memoirs of Mrs. Margarita Fenwart, née Bernecker, the daughter of one of the founders of the "Bohemian Brewery" Bernecker, her father, Eduard Bernecker, together with his brother Heinrich, founded a brewery in 1875. It was the largest in Insterburg. Its extensive and well-kept garden occupied an area of six morgen (morgen is a Prussian unit of area, approximately 0.6 hectares. - admin ). To the delight of passers-by, a magnificent peacock proudly walked around it. Shortly before the "Königsecke" (Royal Corner, now a U-shaped house on Sportivnaya Street. - admin ) residential area was built on its site, a provincial song festival was held there. The brewery flourished, but when Heinrich Bernecker died, his brother created a joint-stock company out of the brewery and moved with the whole family to Berlin.

Before the First World War, small breweries were located on Ziegelstrasse (Pobedy Street), on the corner of Königsbergerstrasse (Kaliningradskaya Street), opposite the district court on Gerichtstrasse (Dachnaya Street) and on Pregelstrasse (Pregolskaya Street).

After the First World War, the Insterburg breweries were bought by the Rückforth brewing concern. In the course of rationalization – as they would say today – this concern stopped production at the plants located on Schlossstrasse and Ziegelstrasse in 1923.

The "Bohemian Brewery", which had been decommissioned, was, however, significantly expanded and remained the only brewery in Insterburg, changing its trade mark to "Bürgerliches Brauhaus AG". Director Werner Bonow.

It is worth dwelling separately on such a necessary and mandatory moment for a brewery as a glacier and cooling.

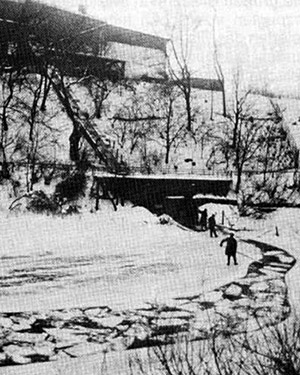

Each of the three Insterburg breweries was located near a body of water from which it could replenish its ice reserves. Thus, the Gafen Pond was located near the Ziegelstrasse brewery, the Schlossstrasse brewery was located next to the Castle Pond, and the Bohemian Brewery was located near the Angerapp River. Although the above-mentioned enterprises had their own equipment for producing artificial ice, natural extraction was still more economically advantageous under the conditions of that time.

When the harvesters with their saws and long hooks went out onto the ice, it became a real event for the Insterburg kids. With huge saws they smoothly made channels in the ice, often one meter thick. Their colleagues, with long hooks, dragged the ice floes to the ice lift or dragged them along the Castle Pond to the loading area near the Green Cat café. Then the ice was delivered by sled to the production cellars. Particularly interesting were the ice lifts, along which ice blocks were lifted from the pond or the Angerapp River to the brewery cellars. Not only we, the children, but also many adults watched this process, frozen to the very feet. So behind the main building of the City Brewery, a trench was laid to the river, along which chopped ice was dragged with chains with hooks at the end into the brewery premises.

Director Bonov writes that the natural ice obtained in this way was used exclusively for cooling the production facilities. Artificial ice was delivered to customers in blocks. At that time, the brewery rented out its refrigerators. These were real monsters, cooled by ice blocks. For this reason, bottled beer always remained cool. Reputable restaurants had their own cellars, supplied with artificial or natural ice. In the warm season, special refrigerated vehicles drove around the city, designed to quench the thirst of lovers of cool beer.

Here is what the last director of the City Brewery, Werner Bonow, writes about beer production and its varieties:

The main raw material for beer was and remains barley. It was crushed, soaked for 2 to 3 days, and sent to the brewhouse. There were large wort kettles in which hops and yeast were added. In the hop separator, the hot wort was separated from excess hops (so that the beer would not turn out too bitter). From the brewhouse, the wort was pumped into a fermentation tank. During storage in this tank, fermentation and conversion into alcohol took place. On its way through various vats, boilers and other vessels, the wort was constantly monitored by the laboratory. The success of the finished product, of course, depended largely on the skills and experience of the brewers themselves. As soon as the correct degree of fermentation was achieved, the wort was pumped into tanks in the lager section for storage, where it was carefully monitored - while it matured.

Filling of barrels and bottles was done by machine. Beforehand, bottles and barrels were washed in a special place, dried and - if it concerned barrels - repaired, renewed, painted, etc. Beer was delivered to the consumer from the factory only in clean containers.

Regarding the volume of beer produced – “output” – Werner Bonow provides the following information: In 1925, 28,000 hectoliters of beer and about 4,000 hectoliters of mineral water were produced. In the last year of production (1944) there were – despite military restrictions – already 62,000 hectoliters of beer and approximately 13,000 hectoliters of mineral water.

Own vehicles, horse-drawn and motorized, were loaded with boxes and barrels from a conveyor belt, after which the products were shipped to customers.

In addition to the famous "Insterburg Double Beer", the "City Brewery" produced export beer and bockbier (Bockbier - a type of German strong beer. Translator's note), brown beer (Braunbier - a type of top-fermented beer. Translator's note), as well as pasteurized malt beer (Malzbier - low-alcohol or non-alcoholic beer. Translator's note), the so-called "Sanitary", with the addition of iron. The latter was supplied in large quantities to the district Women's Clinic on Augustastrasse. The production of tasty mineral water was another thriving branch of the brewery.

As Director Bonov emphasizes - and visitors to the brewery could see this for themselves - the Insterburg "City Brewery" was equipped at that time with the most advanced devices and equipment, which, along with professional personnel, created the best conditions for the production of high-quality products.

Hops were supplied from Nuremberg and Tettnang.

The

installation of the Rückfort cooling system allowed the brewery to become

independent of climate change, which had a positive effect on beer sales. In

1911/12, 32,600 hl were sold, in 1912/13 – 34,600 hl, and in 1913/14 about

35,000 hl. During this period, the City Brewery became the largest beer producer

in the city. The company managed to overcome the crisis of the First World War

by taking over the Bruhn & Fröse plant in Insterburg in 1917 (which had been

producing Bavarian beer since 1890) and the Böhmisches Brauhaus brewery (located

on Zavodskaya Street) in 1918. Thanks to the use of quotas, the City Brewery

received the right to produce 62,000 hectoliters of beer annually. In 1921, the

majority of shares were acquired by the Rückfort concern from Stettin (now

Szczecin), which became the owner of the company. Between 1917 and 1923, the

company's share capital increased to 357,000 marks, and from 1924 it was already

880,000 marks, in 11,000 shares of 80 marks each. The main beer brands in the

interwar period were Insterburger Doppelpils, Insterburger Pilsener and

Insterburger Münchener. In the 1930s, the range was expanded by Insterburger

Schloßbräu. In addition, the plant produced mineral water and lemonade. The malt

house located on the premises produced 25,000 centners of malt annually.

The

installation of the Rückfort cooling system allowed the brewery to become

independent of climate change, which had a positive effect on beer sales. In

1911/12, 32,600 hl were sold, in 1912/13 – 34,600 hl, and in 1913/14 about

35,000 hl. During this period, the City Brewery became the largest beer producer

in the city. The company managed to overcome the crisis of the First World War

by taking over the Bruhn & Fröse plant in Insterburg in 1917 (which had been

producing Bavarian beer since 1890) and the Böhmisches Brauhaus brewery (located

on Zavodskaya Street) in 1918. Thanks to the use of quotas, the City Brewery

received the right to produce 62,000 hectoliters of beer annually. In 1921, the

majority of shares were acquired by the Rückfort concern from Stettin (now

Szczecin), which became the owner of the company. Between 1917 and 1923, the

company's share capital increased to 357,000 marks, and from 1924 it was already

880,000 marks, in 11,000 shares of 80 marks each. The main beer brands in the

interwar period were Insterburger Doppelpils, Insterburger Pilsener and

Insterburger Münchener. In the 1930s, the range was expanded by Insterburger

Schloßbräu. In addition, the plant produced mineral water and lemonade. The malt

house located on the premises produced 25,000 centners of malt annually.

Director Bonow was constantly concerned about using every opportunity to improve the living conditions of his employees. At his instigation, an organization for issuing benefits to those in need was officially registered. In the event of loss of work capacity or upon reaching retirement age, employees were paid 100 Reichsmarks per month. The main requirement was a work experience of at least 10 years. All employees were paid vacation pay. Workers and employees received a Christmas bonus as early as December 10. The malt house was cleared out for the holiday. There, employees and their families sat down at festively laid tables. The "Old Man" (as Director Bonow, who was not yet old, was called at the time) addressed them with a short speech. Children recited their little Christmas poems by heart and received gifts, while wives drew lots, raffling off food and kitchen utensils (for free, of course). The Christmas parties held at the brewery always had a very homely feel to them and everyone felt it because it was one big family.

And so it could not be otherwise that when the party organization demanded that the "Mason" Bonov be replaced, all the company employees, including the production council, stood up for their "Old Man". And the "Old Man" remained...

He stayed with them until 3 p.m. on January 20, 1945, when his remaining workers, 33 men and 8 women, packed up and left before the Russian troops arrived. Despite everything, he never lost his sense of humor, again and again inspiring the downtrodden. His companions sometimes joked bitterly, too. The brave wanderers called him "road referent" after the first ten kilometers of the journey, after 14 days he became a "street expert," and finally was appointed "kilometer Hermann." He willingly talks about this even today. He only says nothing about his deep experiences.

When the sweet aroma of malt from the Munich breweries wafts through the streets, I see the ghost of a peasant cart rumbling through the streets of Insterburg, carrying “brewer’s grain” – the nutritious remains of brewing barley. This is how it once smelled along the entire Hindenburgstrasse…

(source: Insterburger Brief No. 01-02, 1964)

Translation - Evgeny Stewart