Historical graffiti in Cyrillic

Pilgrimage in Ancient Rus

Anyone can leave a note on a famous landmark. But not everyone can get away with it - graffiti (that is the scientific name for inscriptions and images drawn or scratched on walls and other surfaces) on tourist attractions (and not only on them, the walls of ordinary houses are not much different in this sense) are equated to acts of vandalism and are severely punished. At best, you will get off with a fine, at worst, you will end up behind bars.

But it was not always like this, and we can only rejoice at this fact. If it were not for the numerous graffiti covering the walls of temples, columns, steles, statues, caves, monuments (and even the walls of ordinary houses) in different countries, our knowledge of history would be much poorer. Often, graffiti are the only written sources at our disposal relating to a certain period of time. They allow scientists to reconstruct languages, have an idea of what the alphabet was like in ancient times, how and how vernacular speech differed from literary speech, what worried our distant (and not so distant) ancestors. For example, before the discovery of birch bark letters in Novgorod, it was graffiti in Novgorod's St. Sophia Cathedral that were the only paleographic source for the period when writing appeared there. In Kyiv, where birch bark letters were not used, graffiti on the walls of ancient temples are still the main written source for the 11th century.

And among the graffiti on the choirs and columns of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, left in abundance over its more than one and a half thousand year history, there are not only Cyrillic (about 80 of them have already been discovered) and Greek graffiti, but also Scandinavian runes and Glagolitic inscriptions. It is interesting that in addition to the actual inscriptions, there are also many graffiti drawings depicting crosses, arrows, Calvaries and even ships. [1]

In this article we will talk about two truly unique in a certain sense graffiti, discovered not so long ago in France. What unites them is that they were written in Cyrillic at about the same time - at the end of the 12th century. But what is most important is that they were made by Russian pilgrims heading along the Way of St. James to the northwest of the Iberian Peninsula, to Spanish Galicia, to the city of Santiago de Compostela.

But first, let us say a few words about what pilgrimage was in Ancient Rus and the testimonies that the ancient Russian pilgrims left for their descendants. (Here we need to make a reservation that by the word "ancient Russian pilgrim" we mean an Eastern Slav who lived in the territory of Ancient Rus and spoke and wrote in Old Russian and Church Slavonic. By the way, understanding both of these languages is not at all difficult for a modern Russian-speaking person).

The origin of Christian pilgrimage in Europe is associated with the mother of Emperor Constantine the Great, Helena, who in 326, already at a very advanced age, undertook a journey to the Promised Land. During her stay in the Holy Land, Helena founded several churches there, found a cave in which, according to legend, Christ was buried, found the Life-Giving Cross and several other holy relics, which she sent to Constantinople.

The journey of Saint Helena the Equal-to-the-Apostles to the Holy Land served as an example for many European Christians. Already in 333, the so-called "Bordeaux Itinerarium" (Latin: Itinerarium Burdigalense, or "Bordeaux Traveler") appeared - a description of the pilgrimage to Palestine from Bordeaux, which became the first of the known guides to the Holy Land.

It is obvious that pilgrimages (or as they were called in ancient times - walking or walking) to Christian shrines appeared in Russia soon after the country adopted Christianity in the 10th century. The main centers of pilgrimage were the Holy Land and Constantinople, from which, in fact, Christianity came to Rus'. Just over a hundred years later, the first descriptions of the walks of Russian pilgrims appeared. Several descriptions of pilgrimages to Palestine are known, while the number of Slavic graffiti in the territory of today's Israel is significantly more modest (scientific literature describes four Cyrillic graffiti from the Basilica of the Nativity of Christ in Bethlehem [3]) than in Constantinople, which can be explained by both the insufficient study of sacred buildings in the Holy Land for the presence of inscriptions on them, and the comparative difficulty of traveling to those lands, and, accordingly, a smaller number of pilgrims and merchants. But despite this comparative complexity, the connections of Ancient Rus' with the Holy Land are recorded in the chronicles. In particular, the chronicle reports that in 1163 "... 40 men went from Veliky Novgorod from Saint Sophia to the city of Jerusalem to the Holy Sepulcher. And they kissed the Holy Sepulcher and were baptized. And they went, having received the blessing of the Patriarch and the holy relics." Moreover, the first literary description of the pilgrimage that has come down to us was made to the Holy Land more than 900 years ago, at the very beginning of the 12th century, and is called "The Life and Journey of Danilo, Abbot of the Russian Land."

The difficulty of visiting Palestine was also due to the fact that from the 7th century it was under Arab rule, and only when the Crusaders captured the Holy Land and founded several states there, did opportunities for Russian (and European) pilgrims to visit the birthplace of Christianity become greater. The appearance of knightly orders in the Holy Land (the Order of the Templars, the Teutonic Order, etc.), which protected and helped pilgrims, also dates back to this period.

Surprisingly, in the description of his journey, Abbot Daniel (he was presumably a native of the Chernigov lands) does not mention the route from Rus' to Constantinople and back, beginning the description of his journey as follows: “And this is the route to Jerusalem. From Constantinople along the Lukomorye coast, go 300 versts to the Great Sea.” Perhaps there was simply no need for this, since for most Russians the route from Kyiv to Constantinople was clear and uncomplicated, taking approximately two and a half months. [4]

In general, Byzantium was considered for a long time in the minds of Russian Orthodox people to be the highest spiritual mentor and example, especially since the residence of the patriarch was located in Constantinople, this Second Rome.

We have several descriptions of journeys to Constantinople made by Russians in the 12th-15th centuries. They are supplemented by a very representative corpus of ancient Russian graffiti from St. Sophia of Constantinople, which is constantly being replenished.

It should be noted here that graffiti left on the walls of temples and churches are some of the most common inscriptions that have survived since the times of early Christianity. Byzantinist historian Sergei Ivanov expressed his opinion on this matter: “… a medieval person perceived a temple not as an artistic monument that needed to be preserved intact — he himself felt himself to be a part of this temple.” [5] Therefore, people often left inscriptions on church walls and columns addressed to God, a kind of prayer-request, such as “Lord, help your servant such-and-such.” (Although there were, of course, inscriptions of a completely different content, such as a graffito in the same St. Sophia Cathedral in Constantinople, made in the 14th century by a certain Alex Bezneg — “He ruined two souls”). Therefore, most likely, such inscriptions, although not encouraged by local clergy, were not strictly prohibited either. There are examples of graffiti that were started but not finished. This most likely indicates that the writer was forced to interrupt his work for some reason. Among other things, the reasons could have been a ban from the clergy. But at the same time, there are examples of graffiti left by the clergy themselves. For example, again in the same St. Sophia Cathedral in Constantinople there are Cyrillic graffiti of the following content: "Matthew the priest of Galicia", "Lord help your servant Philip Mikitinich, steward of Cyprian, Metropolitan of Kyiv and all Rus'" (14th century), "(Lord help) your servant Yakov Grigorievich, scribe of Gerasim, Metropolitan of Kyiv" (15th century).

A significant number of graffiti are collective inscriptions, sometimes even written by different people. This suggests that group travel was no less common in the past than it is today. Uniting pilgrims into groups made the trip cheaper and less dangerous. In the chronicle we mentioned above, we see that "40 men of Kaliki" set off from Veliky Novgorod to Jerusalem. This refers to the so-called "traveling Kaliki", who later became the heroes of epics and tales, and up until the twenties of the last century were a very noticeable detail of the cultural landscape of Russia. It is believed that the Kaliki got their name from the Latin word caligae, meaning special footwear in the form of short boots, which pilgrims used on their journeys [6]. And if in later times the beggars who begged in villages were called "traveling Kaliki", then originally Kaliki were pilgrims to holy places:

And from the desert, the Efimievs

from the monastery of Bogolyubovo

began to dress up as pilgrims

for the holy city of Jerusalem.

Forty of them with a pilgrim. [7]

Ilya Muromets, who sat on the stove for thirty years, “came into the world” thanks to two such cripples:

When two wandering pilgrims came

to that slanted window,

the pilgrims said these words:

- Oh, you, Ilya Muromets, peasant's son!

Open the wide gates for the pilgrims,

Let the pilgrims into your house.

In Russian epics, the Kaliki are depicted as good fellows, with a slanting fathom in the chest, endowed with remarkable physical strength, combined with spiritual strength. Moreover, judging by how the Kaliki were dressed, they were wealthy people:

They had silk bast shoes on their feet,

black velvet pouches,

fish bone crutches in their hands, and

Greek caps on their heads.

The description of pilgrims in Russian epics allows us to identify their appearance with the way Western European pilgrims dressed: a vest, a cloak, a hat, a bag, and a staff with a curved upper end in their hand - a klyuka.

Travel to Byzantium and Palestine followed established routes, which, due to objective reasons (for example, the conquest of a significant part of Rus' by the Horde), changed over time. In essence, these routes coincided with pan-European trade routes to the East, and before the Mongol conquest, for example, residents of the northwest of Ancient Rus' or Northern Europe went to Byzantium along the well-known route "from the Varangians to the Greeks."

Obviously, it is difficult to draw conclusions about the authorship of many of the graffiti that have come down to us and determine who left them - a pilgrim, a merchant, a member of a merchant ship's crew, someone accompanying an embassy sent by a prince or metropolitan, or even a fugitive. But in any case, they all considered it their first duty, when in Constantinople, to visit Hagia Sophia: "Behold, I have come unworthy to Constantinople. First we worshiped Saint Sophia ...", - this is how the Novgorod Archbishop Anthony described his pilgrimage to Constantinople at the beginning of the 13th century. This is explained by the fact that the believers had the greatest authority (in increasing order) regional, national and pan-Christian spiritual centers. An appeal to God left on the wall of a temple retained its power as long as the temple stood and the inscription did not disappear. Thus, graffiti served as a kind of eternal prayer. And the larger and more significant the temple, the faster the prayer would reach God.

It is appropriate here to return to the already mentioned inscriptions from France. The way to the Holy Land and Constantinople, as already mentioned, was well known to the inhabitants of Ancient Rus. But they also knew the way of St. James, and the cathedral in Santiago de Compostela, in all likelihood, was included in the list of those same pan-Christian spiritual centers. Moreover, the Christians of Ancient Rus went to the Iberian Peninsula, to the “end of the earth” — finis terrae — to the western borders of the world known at that time, to venerate the relics of the apostle.

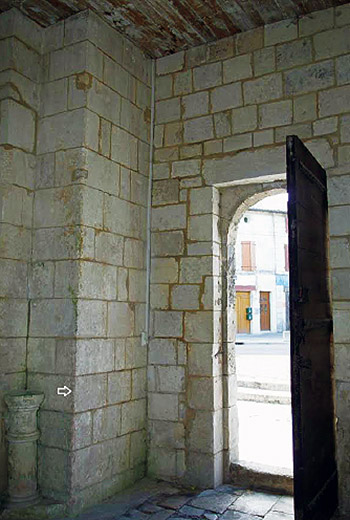

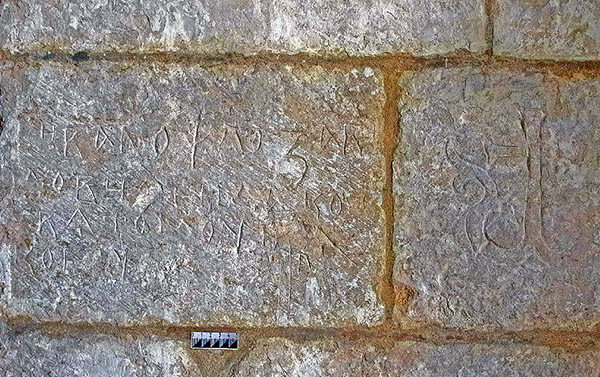

In 2009, during an inspection of the church at the Abbey of Saint-Gilles-du-Gard in Provence, the first Cyrillic graffito in France was discovered [8]. The reasons why the graffito went undiscovered for so long are said to be the poor lighting inside the church and the fact that it was partially hidden under a layer of plaster.

The inscription, located at the bottom of one of the columns supporting the vault of the church, reads:

HELP YOUR SERVE SEMKOVI NINOSLAVICH

Lord, help your servant Semka Ninoslavich

"Gi pomozi" is a standard form of address to God, where "gi" is an abbreviation of the first and last letters of the word "Lord", used for brevity in writing. Based on the letterforms and linguistic features, this graffito dates to the period between about 1180 and 1250. And it was most likely written by a person from the southern or western part of Ancient Rus', but not from Novgorod.

How he ended up in the Abbey of Saint-Gilles, we can only guess. The reason why pilgrims from Rus' could visit the tomb of Gilles the Hermit (or Saint Egidius), the patron saint of the poor, cripples and the mentally ill, is known - thanks to his patronage, it was believed that the future king of Poland, Boleslaw III Wrymouth (1086 - 1138), son of Vladislav I Herman, was born. By order of the latter, at least three churches in honor of Saint Egidius were built on the territory of Poland. At the same time, Boleslaw himself was married in his first marriage to the daughter of the Grand Duke of Kyiv Svyatopolk Izyaslavich, and his two sisters and two daughters were married to Russian princes. In addition, in the Middle Ages, the Abbey of Saint-Gilles-du-Gard was located on one of the four pilgrimage routes that passed through France to Santiago de Compostela - the Toulouse Road. The route from Arles through Toulouse was the southernmost of the four, and to get to it, a Russian pilgrim had to either cross the Alps, heading overland, or somehow get by sea to today's Côte d'Azur.

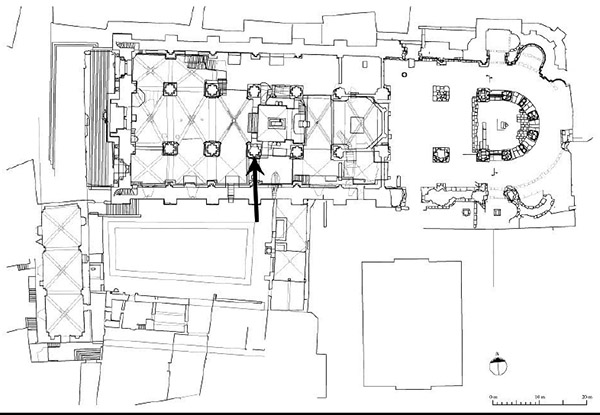

The northernmost route to the relics of Saint James was the Via Turonensis, the Road of Tours, which began in Paris and passed through Tours and Bordeaux. In 2015, another Cyrillic graffito, dating from the 1160s to 1180s, was discovered in Pons, a town on this route, on the wall of the 12th-century Church of Saint-Vivienne. [9] The inscription is located about a metre above the medieval floor of the church, suggesting that it was written by a kneeling person.

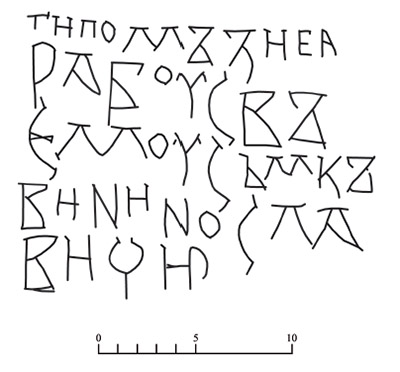

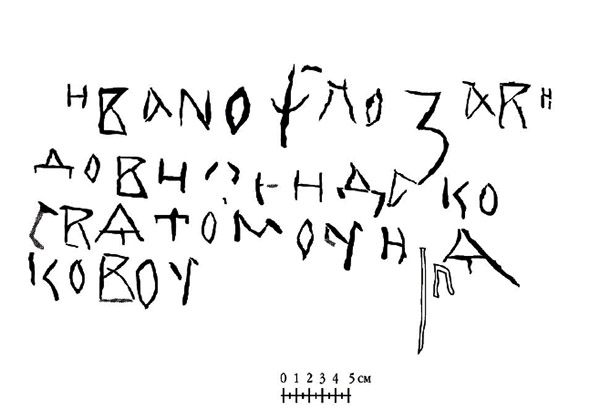

The inscription consists of four lines and looks like this:

IVANO PISALO ZAVIDOVICHE IDA TO SAINT JACOB

Ivan Pisalo Zavidovich, going to Saint James

The paleographic and linguistic features of the inscription indicate that it was most likely written by a resident of Novgorod. On the stone block next to the inscription there is a drawing of a life-giving (flourishing) cross, as uncharacteristic for France as the Cyrillic inscription itself.

The choice of the Tours Road for a pilgrimage to Galicia seems more natural for a Novgorodian than for a resident of southern Rus'. It is possible that he began his journey by sea along the Baltic coast, and landed only in Lübeck, from where he headed on foot towards the Iberian Peninsula, visiting Pons along the way, where in the Middle Ages there was a hospital for pilgrims, which guidebooks of that time recommended as a reliable and hospitable refuge, designed to accept not only the sick and the poor, but also all those suffering on the way to St. James, distributing bread to them.

Turning to statistics, we will see that the number of modern "traveling pilgrims" who have reached the cathedral in Santiago de Compostela by various routes and means from Russia is growing year after year. According to data provided by the pilgrim reception office (Oficina de Acogida al Peregrino de Santiago de Compostela), that is, the organization that issues certificates that a pilgrim has completed his Way to Santiago de Compostela (the so-called "compostelas"), in 2013, 526 Russians received such certificates, among whom were the author of these lines with his son . The following year, there were already 742 Russians, and in 2015 - 874. Despite the steady increase in the number of pilgrims from Russia, in the total mass they make up only a third of a percent. And this is with the current transport (primarily) capabilities. Therefore, we cannot even imagine what difficulties and hardships befell our distant ancestors, who may have spent years getting to distant Galicia, Jerusalem or the Italian Bari.

And the words of those who, having reached their final goal, thought not only about themselves, sound even more valuable to us:

"And God listened to this and the Holy Sepulcher of the Lord, for in all the holy places I have not forgotten the names of the Russian princes, and princesses, and their children, the bishop, the abbot, and the boyars, and my spiritual children, and all Christians I have never forgotten; but in all the holy places I remembered. First I bowed down for the princes for all, and then I prayed for my sins. Apart from all the Russian princes, - and for the boyars at the Holy Sepulcher and in all the holy places. And we celebrated the liturgy for the Russian princes and for all Christians…”

Used Books:

1. Alekseev A.A. Russian graffiti of Constantinople's Sophia. — Works of the Department of Old Russian Literature, No. 51, St. Petersburg, 1999.

2. Artamonov Yu. A., Gippius A. A. Old Russian inscriptions of St. Sophia of Constantinople. - Slavic almanac: 2011. Moscow: Indrik Publishing House, 2012.

3. Artamonov Yu.A., Gippius A.A., Zaitsev I.V. “And with father, and with mother, and with all the brothers...”: two ancient Russian graffitos from the Basilica of the Nativity of Christ in Bethlehem. — Ancient Russia. Questions of Medieval Studies. No. 3 (53), 2013.

4. Maleto E. I. Anthology of Russian travelers’ journeys, 12th–15th centuries. — Moscow: Nauka, 2005.

5. Ivanov S. Walks around Istanbul in search of Constantinople. - M.: AST Publishing House, 2016.

6. Fedorovskaya N.A. On the role of pilgrims in the domestic culture of the 10th – early 20th centuries. — Bulletin of the Chelyabinsk State University. 2010. No. 16 (197).

7. Sreznevsky I.I. Russian pilgrims of ancient times. — Notes of the Imperial Academy of Sciences, v. 1, book II, 1862.

8. Brun A.-S., Hartmann-Virnich A., Ingrand-Varenne E., Mikheev S. Old Russian graffito inscription in the abbey of Saint-Gilles, south of France. — Slověne = Slovenians. International Journal of Slavic Studies, no. 2, v. 3. 2014.

9. Gordin A.M., Rozhdestvenskaya T.V. “Going to Saint James”: Old Russian graffito of the 12th century in Aquitaine. — Slověne = Словѣне. International Journal of Slavic Studies, No. 1, 2016.