Ferdinand Schulz

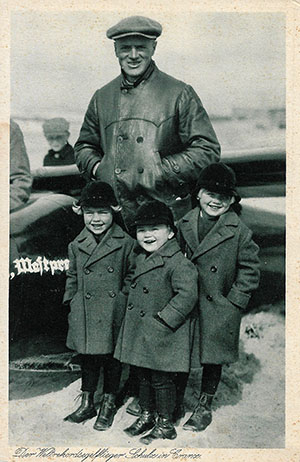

…A joyful, sunny photo – all four are smiling: the pilot in a leather jacket and three kids in identical coats, clearly brothers. The photo was taken in the spring of 1926 on the territory of a glider school, in the dunes near the village of Rossitten (now Rybachy) on the Curonian Spit.

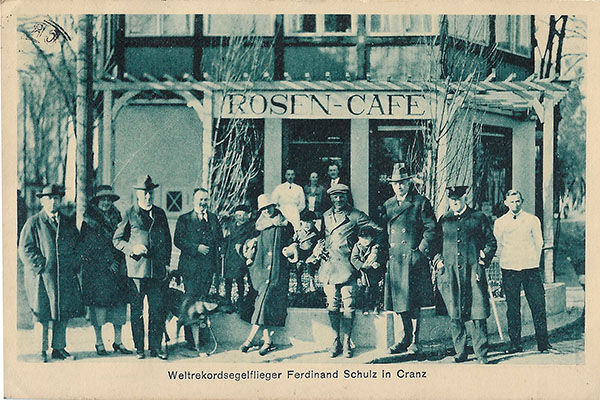

Who is he, this obviously self-confident (the famous German photographer Fritz Krauskopf knew how to capture a person's character) aviator - hands in his pockets, but you can feel that his children are under reliable protection? His name thundered in the world of aeronautical sports in the 1920s - Ferdinand Schulz. The man who was called the "Icarus of East Prussia" lived only 37 years on the ground and in the air.

He was born in 1892 in the village of Pissau (now Piszewo) near Allenstein (now Olsztyn) and was the eldest of twelve children in the family of a village teacher. Since childhood, he loved to make things with his own hands. And in a large family, children grow up earlier: from the age of 12 he lived with relatives in Braunsberg (now Braniewo), where he graduated from high school. He decided to follow in his father's footsteps - to become a teacher. After studying at the preparatory courses in Rössel (now Reszel), he entered the teacher's seminary in Thorn (Torun). In April 1914, the twenty-two-year-old guy was called up for military service and Ferdinand ended up in one of the infantry regiments stationed in Danzig. War. On the very first day, August 1, 1914, he was wounded near Tannenberg and this turned out to be the first of his three wounds. Each time he returned to duty, was awarded the Iron Cross 2nd class, with a personal formulation "for bravery in the face of the enemy." And in early 1917, Schulz wrote a report on transfer to aviation. After completing the air observer courses, he was sent to the Western Front, where on January 2, 1918, he made his first solo flight. This hour became his baptism of fire as a military pilot: the enemy noticed the plane and began to fire at the aerial target from the ground, wounding the second pilot and damaging the machine. Schulz managed to make an emergency landing on his territory, and Ferdinand then pulled the enemy bullet out of the engine with him as a talisman ... Until the end of the war, he made 97 combat sorties, became a squadron commander with the rank of lieutenant, receiving another Iron Cross, this time 1st class.

After demobilization, Ferdinand Schulz returns to work as a teacher. But the sky does not let go...

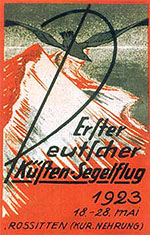

What to do, since according to the Treaty of Versailles of 1919, Germany is forbidden to build motorized aircraft? But gliders - as many as you want. And from 1921, Ferdinand began to design and assemble them in Königsberg, in a workshop in the Rossgarten area. Schulz affectionately called the seven gliders he designed "flying boxes" (Flugkisten).

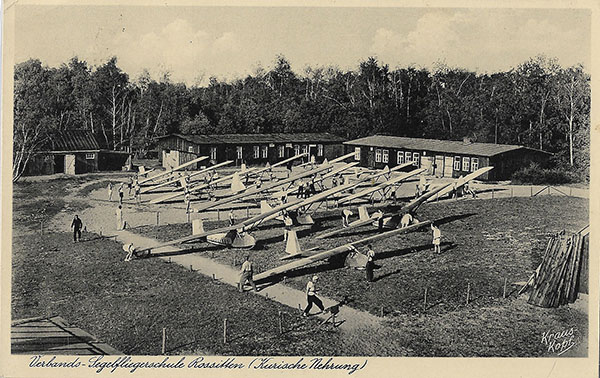

But the "flying boxes" needed to be tested somewhere, especially since he was no longer alone, but with his fellow enthusiasts. The youth needed to study somewhere. The area around Rossitten turned out to be very convenient - sandy expanses and warm ascending air currents, a safe launch pad on Black Mountain. The All-German Glider School, a kilometer from the village, accepted its first cadets in 1924, and in 20 years, about thirty thousand people would gain flying skills here! Pilot and instructor Ferdinand Schulz turned out to be not only a talented person in the sky, but also on the ground - his military and teaching experience had an effect: it remained in the memories that every graduate was grateful to him for the "ticket to the sky." And among those who received a flight license here were people who later became famous, for example, Wernher von Braun - the same one who would invent the infamous V-1 and V-2 rockets.

Ferdinand Schulz was a pioneer of German gliding, a talented self-taught designer of lighter-than-air craft, a pilot and mentor to future air aces. He set several world records in this new sport, and some of his best achievements, in particular, for the duration of flight (12 hours and 6 minutes) and the greatest altitude gain (435 meters), were achieved in October 1925 in Koktebel, at the 3rd USSR (!) gliding championship. As a prize, the German record holder was awarded a bust of Lenin... At that time, seven German athletes came to Crimea to participate out of competition, and they brought their gliders. It is curious that several months before this all-Union championship, a group of Soviet glider pilots attended competitions in Germany. Of course, our people invited their German colleagues to come to the USSR. And a year before the trip to the Union, in 1924, Schulz set a world record in his FS-3 (Ferdinand Schulz-3) glider, nicknamed the "Flying Broom" (the glider was constructed using spruce boards and soldiers' blankets, and was controlled using two wooden broom handles and table tennis racket handles) while flying over the Curonian Spit, staying in the air for 8 hours and 42 minutes! At the same time, Ferdinand sometimes had to participate in competitions outside of the competition, since he was not allowed into the main group of participants due to safety requirements.

As we see, a year later the Germans were so prepared that they were allowed to go abroad, to Soviet Russia. From the archives we learn that the master's students did not go without prizes, just like that, sparingly, without details. But the teacher himself performed more than successfully: the lines about the world records set here that autumn will forever be inscribed in the annals of Koktebel gliding.

But here's what I'm thinking about... 1925, young and nice people dreaming about the future - and it doesn't matter that they speak different languages - meet in an honest friendly fight in the sky that is common to all, and then firmly shake hands on the podium, congratulating each other on their awards. A decade and a half will pass and, surely, many of them, having moved into the cockpits of combat vehicles, will see their recent friends-enemies through the sights of aircraft machine guns. In fights not for life, but for death, all in the same endless sky, where there would be enough room for everyone, if it, the sky, were peaceful... Someone will be awarded the gold star of the Hero, someone will receive the highly respected Iron Cross, and for someone the last sign of honor will be a tin star on a pole or a wooden cross - now in the Crimean steppe that is common to them...

Ferdinand Schulz walked – no, flew – further, and by 1927 he held all the world records in this sport. Fate is often unfair to brave pioneers – on land, at sea or in the sky: a few years later, Icarus from East Prussia would set off on his last flight… Schulz would crash over the city of Sztum (now in Poland) on June 16, 1929. Together with his partner Bruno Kaiser, he was taking part in the ceremonial opening of a monument to those who fell in World War I. The pilots were supposed to fly the Marienburg motor plane over the city and drop a memorial wreath on Bismarck Square. But the irreparable happened – the plane’s wing strut broke – and instead of a wreath, the Marienburg crashed onto the city’s cobblestones…

And one more thing: our short, like the life of the German falcon Ferdinand Schulz, story began with the word "smile". So, those people who knew him said that "iron" by nature Schulz was a gentle and kind person, he even conducted classes with young people, smiling. Maybe this is also why many people still remember him.

Evgeny Dvoretsky "Samland. Kranz and the Curonian Spit in Old Postcards"