Dating of Russian pre-revolutionary postcards

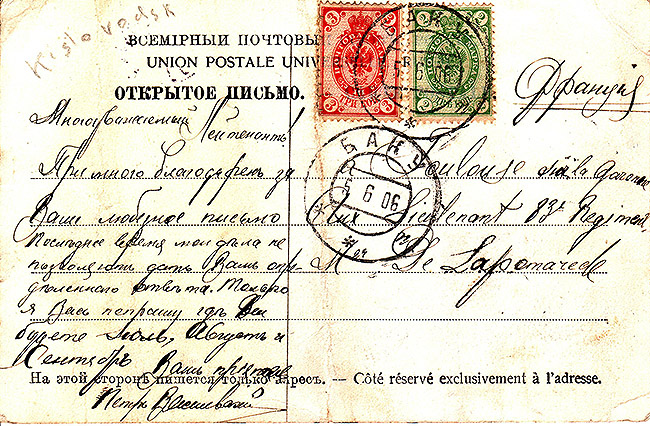

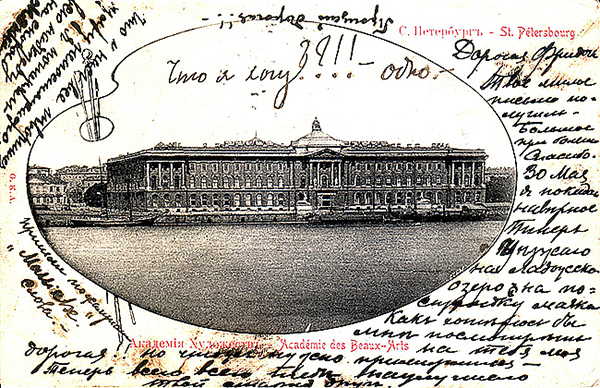

Dating (or, in a broader sense, attribution) of old postcards is sometimes a very difficult task. We have already briefly touched on this issue. Sometimes the date (usually the year) was directly indicated on the postcard, but more often than not, the publishers did not. It is possible to determine the approximate date of printing of the postcard if the postcard went through the mail. Often the sender indicated the date of writing the postcard either at the beginning of the message or (less often) at its end. Also, postmarks, if they are clearly legible, allow us to determine the dates of receipt of the postcard at the sender's post office and the recipient's post office. In these cases, we can confidently determine the date no later than which the postcard was printed. Obviously, before the sender writes a message on the postcard, he will need to at least purchase it, and before that it must be delivered to the place of sale from the printing house. This period is difficult to determine, but it can be assumed that in large cities the time that passed from the moment a postcard was printed in a printing house until it went on sale could take several days, at a minimum. If part of the print run was sent for sale to regions or other countries, and especially when the print run was printed abroad, which was not uncommon, this time, for obvious reasons, increased.

The method of printing postcards does not make the dating process much easier. Especially if we consider that pre-press preparation, for example, of lithographic postcards, could take several months. In addition, the use of one or another printing method often depended not on the development of technical progress, but on the presence or absence of the appropriate printing equipment at the publisher. Therefore, here we can talk about rather conditional time limits associated with the earliest appearance of one or another printing technology, as well as the type of cardboard or paper.

A postage stamp attached to a postcard can help to date it very, very approximately, since the appearance and face value of stamps have not changed for a long time. Only the presence of semi-postal (charity) and jubilee stamps on postcards in combination with other features can somehow help in attributing postcards. By the way, even at present, when postage stamps often indirectly indicate the year of their issue (for example, on jubilee stamps), it is also not easy to determine the age of a postcard, since the time of purchase of the postcard by the sender and the stamp attached to it can be separated in time by decades, while the stamp itself could have been lying with the sender for some time.

It is easy to determine the time frame for printing postcards based on what is depicted on them. For example, a postcard dedicated to an event cannot be printed before this event occurred. This applies to various political, military and cultural events (such as battles, theatrical performances, exhibitions, speeches by famous people, etc.), natural disasters, accidents, etc. Also, the construction or, conversely, the demolition of some architectural objects, monuments, restoration work that led to noticeable changes in the appearance of such objects, certain objects or mechanisms (cars, bicycles, locomotives, airplanes, etc.), posters or advertising of goods that ended up on a postcard can significantly help in determining the time, if not the printing of the postcards, then at least the date of the photo taken for printing on this postcard.

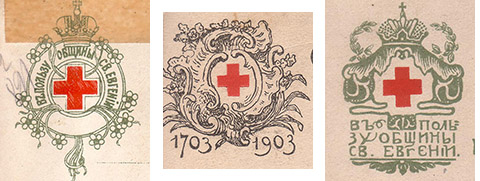

The publisher's imprint and the design of its trademark on the postcard can also serve as a help for attribution if there is information about the time of the appearance of a particular publishing house (or printing house) or, conversely, its closure.

But below we will talk about the external features related to the postcards themselves, issued in Russia, that can be used to date a particular postcard with an accuracy of sometimes up to several years. These include the division of the back of the postcard by a vertical line into two parts - the address and the message, the set of mandatory inscriptions on the postcard, their spelling, etc. In other words, knowing the history of changes in the external appearance of a postcard makes it easier for collectors to attribute it.

So, here are some external signs for dating postcards:

Postcard size. The standard adopted at the Second World Postal Congress in 1878 defined the size of a postcard as 14 by 9 cm. All pre-revolutionary postcards in Russia corresponded to this size. Only in 1925 did they begin to print postcards measuring 14.8 by 10.5 cm.

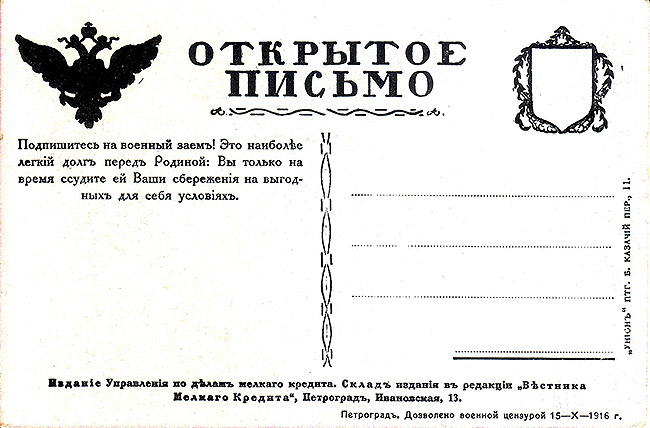

Spelling. It is obvious that the spelling reform, which led to a change in the spelling and the exclusion of some letters from the Russian alphabet, was reflected, albeit not immediately, in the printing of postcards. Having begun in 1917, the reform continued for at least the entire next year. And the farther from the capitals, the later its visible results became visible. During the Civil War, some territories not controlled by the Soviet government continued to use the pre-reform style of writing. But, nevertheless, the lower time frame (not earlier than 1917) for some postcards printed taking into account the reform can be determined.

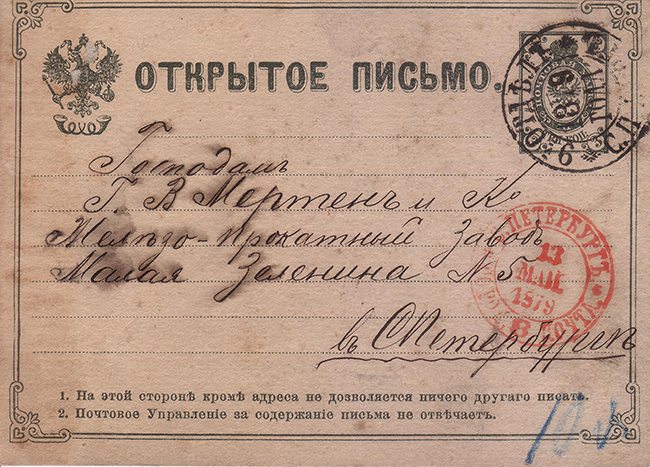

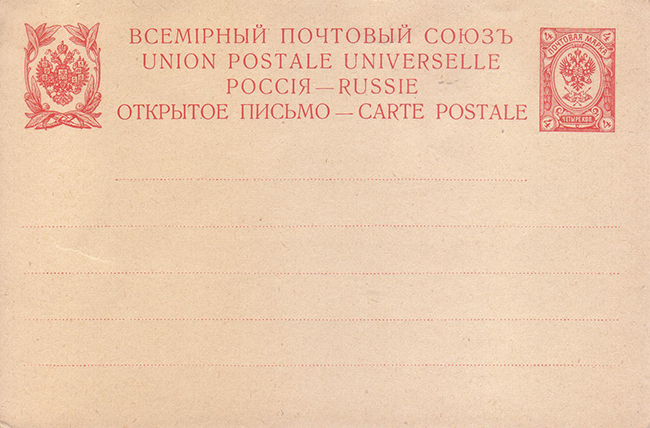

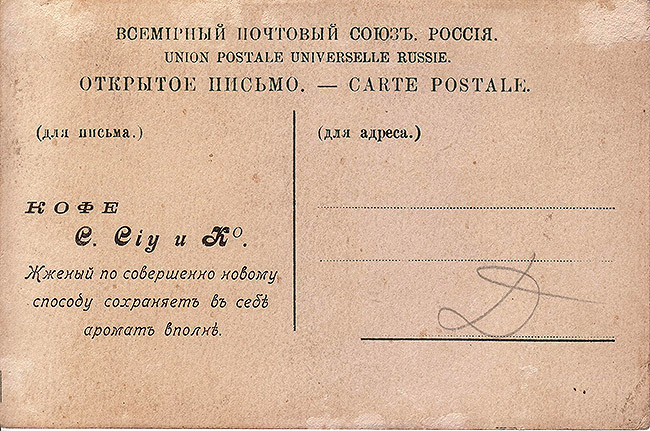

Until October 19, 1894, postcards for the Russian postal service were printed exclusively by the Expedition for the Procurement of State Papers, which was part of the Ministry of Finance. Private publishers were not allowed to print postcards. Therefore, an indication of a private publisher on a postcard could only appear at the very end of 1894. The basic requirements for postcards issued by private publishers were no different from those for state postcards. The exception was a ban on private publishers printing the state emblem and stamp on the postcard. However, it was allowed (with certain restrictions) to print decorations in the form of vignettes and advertising on the back of the postcard. The address side of postcards printed for circulation within the Universal Postal Union was required to contain the inscriptions in Russian and French “Universal Postal Union. Russia” and “Open Letter”.

The earliest illustrated postcards appeared in Russia in 1895.

On February 16, 1904, the Main Directorate of Posts and Telegraphs issued a circular allowing the side of the postcard form intended for the address to contain not only the address, as had been prescribed previously, but also the text of the message. For this purpose, it was divided by a vertical line. The right margin was intended for sticking on the stamp, postmark and address. The left margin was used for the message. Obviously, publishers did not immediately begin printing postcards with a divided side, previously intended only for the address. The first examples of such postcards date back to the summer of 1904. Abroad, similar steps were not taken by member countries of the Universal Postal Union at the same time. Great Britain was the first to do so, in 1902. France did so in the same year as Russia, and Germany only a year later, in 1905.

Until April 20, 1906, the postcards indicated the date of permission for printing from the censorship committee. From then on, prior censorship permission was not required for printing postcards, since control over printed publications began to be carried out after their publication. During the First World War, some postcards again featured inscriptions with references to permission for printing from the military censorship.

On September 7, 1908, the requirement for the mandatory presence of the inscription “Open Letter” on postcards from private publishers was cancelled, and on May 1, 1909, this inscription was replaced by another one – “Postal Card”, which was a tracing from most European languages – post card, postkarte, carte postale, cartolina postale, etc. Here again it should be emphasized that later, several years later, postcards were published that still had the inscription “Open Letter”.

The pictorial side of a postcard can also provide some clues to its dating. On early postcards, issued before the beginning of the 20th century, the image on the postcard occupied from one to two thirds of its area. Then the image began to take up more and more space, leaving only a narrow strip (usually) along the bottom or (less often) right edge for the text of the message. This limitation of free space forced senders to resort to various epistolary tricks: to write the text along all four edges and even on the image itself. However, with the division of the address side by a vertical line and the appearance of a special field for the message, postcards with a strip below or to the right of the image gradually began to disappear from sale.

Sources:

Zabochen M. From the history of the introduction of the open letter in Russia. - Philately of the USSR, 1972, No. 4

Larina A.N. Illustrated postcard: issues of attribution. — Bulletin of the Russian State University for the Humanities. Series: Literary studies. Linguistics. Cultural studies. 2012, No. 6

Tretyakov V.P. Open letters of the Silver Age . - St. Petersburg, Slavia, 2000