The Court of the Grand Master around 1400

This article is based on two works: a translation of a part of a chapter from the work of the historian Christopher Herrmann “Der Hochmeisterpalast auf der Marienburg. Concept, Development and Nutzung der modernsten europäischen Fürstenresidenz um 1400” and the dissertation of Tatyana Igoshina “The Court of the Supreme Master of the German Order in Prussia in the Late 14th – Early 15th Centuries”.

The Master, as the head of the Teutonic Order, was in the position of "first among equals" and, according to the statutes, was not an autocratic ruler. However, his position differed significantly from the other brothers of the Order. The Rules prescribing food provide the first signs of the exclusivity of the Master - if he was entitled to drink like the other brothers, then he received meat and fish as for four, in order to divide it at his own discretion among the guilty brothers (PERLBACH, p. 67). According to custom, the Master was entitled to several horses - one war horse, three ordinary horses and one ceremonial horse, as well as one pony (PERLBACH, p. 98). For the duration of his travels, he was also allocated two pack animals. The privileges granted to the Master by the Rules were his own chambers in the convent building - (PERLBACH, p. 68), in which he could also take food during a long illness.

Custom also ascribes to the Magisters a small group of servants and attendants. According to the eleventh custom, the retinue of the Grand Master was to consist of the following twelve persons: a chaplain and his apprentice with three horses, a turcopol (bearer of shield and spear), a second turcopol (messenger), a third turcopol (chamberlain), a fourth turcopol (squire in war), a cook with a horse, a brother sariant (shepherd), two brother knights as attendants, and two knechts as messengers (PERLBACH, p. 98). Of these twelve persons, only eight were constantly in the vicinity of the Grand Master, since the messenger, messengers, and squire performed their duties outside the residence.

Over time, the Master's retinue grew and increased. This process intensified with the transfer of the Master's residence to Prussia and continued until the secularization of the Order. In Marienburg there was a large number of various service personnel and, at the same time, a separate system of services existed that provided for the needs of the Supreme Master himself. In total, the Master's court numbered from 100 to 125 people, some of whom lived in the Master's palace. By comparison, the court of the Bishop of Ermland numbered almost 100 people (JARZEBOWSKI, p. 249). Only a small number of people belonging to the court were members of the Order as knights or priests. The chaplain, the Master's kumpans and, in some cases, the kitchen master, the cellar master and the horse marshal were definitely members of the Order. Some scribes or notaries of the Supreme Master's chancery came from the circle of priests of the Order. The vast majority of servants came from the urban bourgeoisie or the rural population. The nobility was represented only as the Grand Master's diners.

Below is a detailed account of the Grand Master's servants and retinue around 1400.

The Kumpans (Kumpan) of the Supreme Master and their knechts

In the immediate vicinity of the master were two kumpans, a senior and a junior, who lived directly under the master's chambers and were responsible for various tasks. In the Marienburg Treasurer's Book (Das Marienburger Tresslerbuch, MTV), kumpans are mentioned many times, as they paid for the master's various commissions and affairs, and sometimes also looked after the master's guests.

The Supreme Master's Cumpan Arnold, whose activities can be traced between 1401 and 1408, often received money to be paid on behalf of the Master for various purposes (MTB, 119, 285). In 1402 he accompanied Prince Svidrigailo from Engelsburg to Kulmsee (MTB, 163), in 1406 and 1407 he went to Gotland on behalf of the Master (MTB, 401, 431), and in 1408 to Kovno (MTB, 459). Finally, in 1408 he was appointed bailiff of Neumark and on this occasion received a stallion as a gift (MTB, 495).

The Cumpans also figure as witnesses in most of the charters issued by the Grand Master and were therefore present at the relevant deliberations.

The institution of compans, however, was not limited to the retinue of the Grand Master; they also existed in the retinues of other Grand Administrators, although only the Master had two compans. The corresponding provision is contained in the Rules of the Order, where in the eleventh custom it was stipulated that the servants of the Grand Master should include two "comites". The first known compan of the Master by name is mentioned in 1312 (PUB 2, Nr. 76: "Frater Gebehardus de Glyna socius magni commendatoris").

The Master's Cumpans were mostly young knights at the beginning of their careers in the Order. Some of them later became Grand Stewards or Masters. Ulrich von Jungingen, Konrad and Ludwig von Erlichshausen were Kumpans of the Grand Master at the beginning of their careers. Heinrich Reuss von Plauen (1336-1338) and Kuno von Liebenstein (1383-1387) managed to go from Kumpan to Grand Komtur. Of the eight Kumpans of Rhenish origin under Winrich von Kniprod, seven later rose to the rank of Stewards, two of whom even became Grand Stewards. Each Kumpan of the Grand Master had his own Knecht, but almost nothing is known about their activities. In addition to the usual support services for the Kumpans, the Knechts were sometimes sent on various missions on trips, and it is in such cases that they appear in the MTV. Thus, in 1405, Matthijs Elnisch, a knight of the kumpan Arnold, brought stallions as a gift from the Supreme Master to the Grand Duke Vitovt (MTB, 353). In 1408, the knight Hannos delivered wine to the Grand Duchess of Lithuania (MTB, 470).

It is not known where the knechts lived in the palace. Most likely, their beds were in the chambers of the kumpans.

On the institution of the Grand Master's kumpans, see VOIGT 1830, p. 233f; MURAWSKI, p. 24; JÄHNIG 2011, p. 86f; JÓŹWIAK/TRUPINDA 2011, pp. 227-229; JÓŹWIAK, pp. 150-152.

There is no special study on the Grand Master's kumpans to date.

The senior and junior chamberlains (Kämmerer) and their boys

Of all the servants, it was the two chamberlains who maintained the closest personal contact with the Grand Master and carried out numerous errands, purchases and commissions for their master. This is evident, for example, from the fact that the senior chamberlain Timo is mentioned on 240 pages in the MTB (MTB, 648). No other person was mentioned so often, even approximately. The chamberlain carried out almost all minor and major daily tasks in the name of and on behalf of the master. He received an annual salary of 100 marks (JÄHNIG 1990, p. 71 (list of servants for the period 1393-1407)) and was thus one of the highest paid courtiers. The first known documentary mention of a chamberlain dates back to 1372, when Thomas de Heinbuch ("dicti domini magistri camerarius") appeared on the list of witnesses of a notarial document (CDW 2, no. 463). But since the chamberlain is mentioned in the eleventh custom cited above, he was already with the master as a servant in the 13th century. However, otherwise chamberlains only rarely act as witnesses, unlike, for example, the cumpans, who are almost always found in the lists of witnesses to the deeds of the Grand Master. This indicates that the chamberlains were mainly concerned with the practical issues of the master's life, but did not take part in meetings and conferences.

The chamberlains were mainly responsible for all matters related to the residence of the Grand Master. The precise description of their duties would be comparable to that preserved for the chamberlain of the Bishop of Warmia (SRW 1, 326f; Ordinancia der Burg Heilsberg (um 1470), FLEISCHER, S.810–812; JARZEBOWSKI, S. 101). Accordingly, the chamberlain was responsible for the furnishings of the Master’s chambers and also for monitoring who entered and left it, which had to be kept secret. He monitored all those who rendered personal services to their master in any form. In particular, he had to instruct and train the servants (FLEISCHER, S. 811 – “The chamberlain must instruct the master’s squires in how to behave and instruct them in decorum and manners”). When the master left his chambers, the chamberlain had to accompany him.

At least the Grand Chamberlain had his own chambers, which are described in the 1415 account book of the Hauskomtur as "unsers homeysters kemerers kamer" (AMH, 179). Another mention of "dez kemerers kamer" occurs in 1416 (AMH, p. 208). Where this room was located cannot be said with certainty. Due to the constant proximity of the chamberlains to the Grand Master, a small room to the east of the corridor leading to the Grand Master's chambers could have been used for this purpose. It is possible that both chamberlains used this room, since the accounts mention two keys to this room. However, it can be assumed that the junior chamberlain slept in the Grand Master's chambers, where a simple sleeping bench stood next to the Grand Master's large canopy bed (AMH, 247).

The chamberlains also had boys at their disposal, but there is only one entry in the MTB about them: in 1407, white-grey cloths were bought for the chamberlain's boys (MTB, 441): "item 4 m. vor 2 wysgro laken des meysters kemerern jungen und cröpeln". No detailed information is known about the duties or sleeping places of these boys. It is possible that the boys were identical to the boys of the Grand Master, who were supervised by the chamberlains.

On the role of chamberlains, see JÓŹWIAK/TRUPINDA 2011, SS. 247-249.

The High Master's Boys (Jungen)

The Supreme Master had several boys in his service. They were clothed at the expense of the Master (In 1400 the Master's boy Jacob received a tunic (MTB, 87), and in 1440 the Master's boy Kaspar was provided with a cloak, a caftan and chausses (OBA, no. 7794; JÓŹWIAK/TRUPINDA 2011, p. 250)) and accompanied him or the envoys of the Order on diplomatic missions (The Master's boy Ivan traveled to Birglau in 1408 (MTB, 496) and accompanied Dietrich von Logendorff to England in 1409 - "item 1⁄2 m. Ywan dem jungen zerunge, als her mit her Ditteriche von Logendorff ken Engelant zoch." (MTB, 541). In 1416, all the boys of the Grand Master were sent to Danzig (AMH, 196).

In analogy with the description of the duties of the boys of the Bishop of Warmia, it was probably also the duty of the Grand Master's boys to serve their master during meals, in particular to lay out the dishes and cutlery on the master's table, as well as to clean and store them after the meal (SRW 1, p. 327; FLEISCHER, p. 811). The boys lived together in one of the rooms, the exact location of which is unknown, but presumably it was in the palace of the Grand Master or near it. In 1417, the chambers in which the three boys serving the Master slept were remodeled (AMH, 282). It is possible that the chambers were located in the annex to the north of the chapel, where the chambers of the chaplain's students were also located.

For boys, see JÓŹWIAK/TRUPINDA 2011, pp. 249–251.

Chaplain of the Supreme Master (Kaplan) and his students

One of the most important confidants of the Master was his chaplain (the special position of trust and the duty of secrecy can be judged from the oath that the chaplain took to Konrad von Erlichshausen (KUBON/SARNOWSKY, p. 253f)), who was also responsible for the chancery. Under Heinrich von Waldick, chaplain from 1326 to 1344, the chancery of the Master was probably created (cf. ARMGART, p. 148). From Heinrich onwards, chaplains were also regularly mentioned as witnesses in the charters of the Grand Master. As early as the 13th century, the personal chaplain belonged to a small circle of servants who, according to the eleventh custom of the Order, were under the control of the Master, and was recruited from the group of priests of the Order. He also took on the function of confessor to the Grand Master, an important task that required a close personal relationship of trust (In 1405, the Master's chaplain Johannes Ochmann received the black robe, and in the MTV he is described as the Master's confessor on this occasion - "item 3 m. 8 scot. vor 8 elen swarzes gewandis her Johannes des meisters bichtvater" (MTV, 351)). Therefore, newly elected Grand Masters usually appointed a new chaplain soon after taking office. An exception is Heinrich von Waldicke, who served as chaplain to four Grand Masters from 1326 to 1344 (with a four-year break).

As with the cumpani, the function of chaplain to the Grand Master could become a stepping stone to a higher ecclesiastical career, which in some cases led to the rank of bishop.

The following chaplains later became bishops:

Rudolf (1312-1316, chaplain to Karl von Trier, probably identical with the later bishop of Pomesania),

Wikbold Dobbelstein (1352-1363 chaplain of Winrich von Kniprode, from 1363 Bishop of Kulm),

Martin von Linow (1383-1390, chaplain to Konrad Zöllner von Rothenstein, elected Bishop of Culm in 1390, but not confirmed by the Pope, later served as dean of the Culm Cathedral Chapter),

Arnold Stapel (1397-1402, chaplain of Conrad von Jungingen, appointed Bishop of Pomesania in 1403),

Johannes Ochmann (1402-1405 chaplain of Conrad von Jungingen, from 1405 Bishop of Reval),

Kaspar Linke (1433-1440 chaplain of Paul von Rusdorf, from 1440 bishop of Pomesania)

Sylvester Stodevescher (1441-1448 chaplain of Conrad von Erlichshausen, from 1448 Archbishop of Riga)

Andreas Santberg (1449 chaplain to Conrad and Ludwig von Erlichshausen, elected Bishop of Kulm in 1457, but died before taking office).

The chaplain was probably also responsible for the spiritual culture of the master. Thus, through the chaplain of the master Arnold, in 1400 a frame was paid for for 3 marks (MTV, 62). This frame was intended for the "mappa mundi" - a map of the world, which was going to be hung on the wall in the chapel as a visual illustration of the Christian picture of the universe.

The Master's chaplains also accompanied the Grand Master on his journeys and had their own carriage. In 1406, the Treasurer's Book mentions the carriage of the Grand Master's chaplain Gerhard - "item 3 m. vor her Girhardts des meisters capellans wagen" (MTB, 415).

The chaplain's quarters were in the chancery. The chaplain looked after the apprentices, but their number is unknown. Their education was certainly aimed at preparing them for a career in the priesthood and in any case included reading, writing, Latin and church singing. According to the Heilsberg Ordination, the Bishop of Warmia selected gifted apprentices for training so that they could later serve him as notaries or even pursue a career in the priesthood (cf. SRW 1, p. 333; FLEISCHER, p. 817). According to MTV, the apprentices received small sums of money on several occasions as a thank you for singing in the chapel of the Grand Master. For example, in 1402 (MTB, 383): "4 cattle given to the apprentices who sang in the chapel of our master on St. Dorotheus's Day." They also sang in 1406 during the visit of Grand Duchess Anna to the Master's chapel (MTB, 179f): "also 8 scots for the scholars who sang in the Master's chapel. (…) 2 scots for the students who sang in the Master's chapel on St. Margaret's Day." It is also mentioned that a student guarded a lamp, possibly in the Grand Master's chapel (MTB, 180). In 1399, the MTB reports that a student was sent to Rome as a messenger to the procurator of the order (MTB, 20).

The students lived in a room in the annex north of the chapel, and the expense book of the Marienburg house lordship several times mentions repairs to the roof over the chaplain's students' room. Thus, in 1415 (AMH, 189f) it states: "item 9 sc. vor cleyne stobichcen bey dem borne czu decken und des kapplans schuler kamer czu decken". Similar entries are found in 1415 (AMH, 181) and 1418 (AMH, 306).

On the position of the chaplain in general, see ARMGART, SS. 118-120.

The Master's Lawyer, His Scribes and Servants (Jurist/Syndikus)

The increasing importance of writing in administrative and diplomatic work meant that the Grand Master increasingly had to call on legally trained specialists in his chancery, in addition to the chaplain and scribes. For this purpose, the Grand Master had his own lawyer (advocate/syndic). It is impossible to say with certainty when a lawyer was first hired in addition to the chaplain. However, it was at the latest under Master Conrad von Jungingen, who chose the Pomesanian cathedral pastor Johann Reimann for the position. Together with Johann Marienwerder, Reimann was the confessor of Dorothea of Montau and played a decisive role in the beginning of her canonization process. In 1393, he entered the service of the Grand Master ("des homeisters iuriste") and gave up the pastorate, but remained a canon. In February 1398 he was given instructions for the negotiations he was to conduct as the Order's envoy with the German princes (CDP 6, 165–167). Between 1403 and 1409, Johann Reimann appears several times in the MTB. The entries mainly concern the calculation of his annual salary of 40 marks, which made the lawyer one of the Master's highly paid servants. Annual salary lists are found for the years 1403–1409 (MTB, 235f, 342, 381, 420, 441, 460, 528). In addition, he continued to receive an allowance as a Pomesanian canon, so that his overall income was quite substantial. In addition, the jurist received a diner (MTB, 300 (1404): "item 10 m. meister Johannes Rynman zu syner dyner cleidunge am dinstage noch lnvocavit") and an allowance when he accompanied the master on trips (MTB, 298). The importance of the jurist can also be judged by the fact that he had at least one personal scribe and diner. His scribes Rulant (1404/05) and Laurentius (1406/08) are mentioned several times, for they often received an annual salary for their master from the Grand Treasurer (MTB, 298, 342). Diner Kirstan is mentioned in 1409 (MTB, 528).

For Johann Reimann, his work as a lawyer at the court of the Grand Master became a springboard for a more significant career, since in 1409 he became Bishop of Pomesania. A comparable rise can be seen in his successors as Magister's lawyers, since both Johann Abesir (1411-1415) and Franz Kuhschmalz (1417-1424) rose to the position of Bishop of Warmia (BOOCKMANN 1965, p. 136).

The life and work of Laurentius Blumenau, the last jurist of the Grand Master in Marienburg, are best known, since Blumenau's biography was the subject of a dissertation by Hartmut Boockman (BOOCKMANN 1965). Blumenau, who came from a merchant family in Danzig, studied in Leipzig, Padua and Bologna from 1434 to 1447 and was well prepared as a doctor of law. He entered the service of the Grand Master in 1446/47 and remained in office until December 1456 - as one of the last loyal supporters of the Master, who was captured by mercenaries. Blumenau was a cleric, but apparently not a priest of the order. According to Hartmut Boockman, Blumenau worked mainly in the diplomatic service and traveled several times as an envoy to the imperial court in Vienna and to the Roman Curia. Between his many journeys there were also longer stays in Marienburg, where he dealt mainly with legal questions of the concept and strategy of the Order's policy. From 1450 onwards, the conflict between the Order and the Prussian Confederation increasingly became the focus of Blumenau's activities, especially the trial of the Confederation at the imperial court. In addition, the lawyer also participated in the delegations of the Order that negotiated with the Polish king in 1454/570.

Laurentius Blumenau, whom the Grand Master called "the physician of our court" or "our adviser", received an annual salary of 140 marks (during the crisis, from 1452 onwards, the salary was no longer paid, so that Blumenau reported in a letter to the Bishop of Augsburg in 1455 that he was penniless and owned only his life (BOOCKMANN 1965, pp. 54-56)), significantly more than Johann Reimann, but on the other hand he had no additional income.

Blumenau had several scribes, according to some sources four in 1456 (SRP 4, 180), so that the lawyer managed a kind of "legal department" in addition to the chancery. Blumenau had his own room in the palace of the Grand Master, as can be seen from the report of a dramatic incident on August 21, 1456 (SRP 4, 175; BOOCKMANN 1965, p. 60). After fruitless negotiations with the Grand Master, the frustrated leaders of the mercenaries confronted Laurentius Blumenau in front of the Master's chambers, threw him to the ground and stole the key to the apartment. They then went straight to the lawyer's room and plundered it. Blumenau lost 1,000 guilders in the process, which shows that he had nevertheless amassed some wealth despite the lack of a salary.

The increased importance of the Grand Master's advocate was a result of the increasingly complex legal and diplomatic practices of the first half of the 15th century. Although the management of the judicial system and administration was still the responsibility of the territorial leaders of the Order at that time, in the area of international diplomacy the brothers increasingly relied on the knowledge and experience of lawyers. This concerned in particular contacts with the imperial court and the Curia in Rome (BOOCKMANN 1965, p. 144; NÖBEL 1989, p. 69f). Typical was the communication between the procurator of the Order in Rome and the Grand Master's advocate and the chaplain in Marienburg. The procurator described the situation to the Grand Master in a simplified and abbreviated form in German. However, a more detailed discussion of the problem took place in detailed Latin letters to the chaplain or lawyer. They were then required to inform the Grand Master orally (BOOCKMANN 1965, p. 148).

On the master's lawyer, see VOIGT 1830, p. 234f. On Reimann's biography, see WIŚNIEWSKI 2001b; GLAUERT 2003, pp. 479-486.

Scribes/Notaries (Schreiber/Notare) and assistant scribes of the Chancellery of the Supreme Master

In the first half of the 15th century, two or three chief scribes or notaries are known to have been in the service of the Grand Master at any one time. The clerical staff who performed simple clerical services are called "journeymen scribes" (ARMGART, p. 232). Formally, notaries differ from ordinary scribes in that they have the right to issue notarial documents. For this reason, the names of notaries are well preserved in written sources, while ordinary scribes remain nameless. In addition, there were several journeymen/auxiliary scribes (SRP 4, 175), illuminators, errand boys and apprentices, whose number, however, is difficult to estimate and may have fluctuated.

In 1400 (MTB, p. 57: "item 10 scot den briefjungen oppirgelt.") several errand boys are mentioned. In 1445, the bailiff of Stumm asked the Grand Commander whether he could send a boy to Marienburg to become an errand boy (GStA, OBA, no. 8740: "Ouch bitte ich gnediger lieber her Großkompthur umb one of them, the old man zu Marienburg in the briefing room could give one of them").

Notaries were legally trained clergymen, but generally not priest-brothers of the Teutonic Order.

A well-documented example of an academic career as a notary is Hoike von Konietz, who served in Marienburg in 1395–99 (ARMGART, SS. 250–252). He was educated in Prague in 1384 and entered the chancery of the Grand Master as a lawyer. After leaving the chancery, he continued his academic work in Prague in 1402 and then returned to Prussia, where he is recorded as an official [1] of Kulm in 1406. At the same time, he carried out diplomatic missions for the Grand Master.

Until the middle of the fourteenth century almost all notaries came to the Master's office from outside Prussia, while later they were almost exclusively from Prussia. A notable exception in the later period is Johann von Lichtenwalde, a cleric from the diocese of Posen, who was first a notary in the service of Grand Duke Vitovt and transferred from there to the Grand Master in 1409 (ARMGART, SS. 269-271). A good knowledge of Lithuanian conditions undoubtedly played a role in the Master's decision to appoint Johann to his office.

Over time, in addition to the notaries, the lawyer, who was the closest advisor to the Grand Master and was not subordinate to the chaplain, played an increasingly important role in the structure of the clerical staff. In a document from 10 December 1403, drawn up in the council chamber of the Grand Master (“in loco sui consilii”), the Magister’s lawyer Johann Reimann is listed as a witness before the Magister’s chaplain (CDP 5, no. 137; REGESTA 2, no. 1498). If he had been subordinate to the chaplain, he would have been placed after the chaplain in the order of seniority. Since Reimann was the provost in Marienwerder (HECKMANN 2014, p. 157), a higher rank was also justified.

The total number of chancery staff subordinate to the chaplain ranged from six to ten people. The increasing importance of scribes, notaries and lawyers in the management of the office of the Grand Master can be demonstrated not only quantitatively, but also reflected in other areas. Thus, from 1392 onwards, two scribes/notaries regularly appeared on the list of witnesses in the charters of the Master issued in Marienburg (ARMGART, p. 244). This suggests that the chief scribes were regularly present at the meetings of the council of the territorial rulers and were probably in demand there as legal advisers. When the Master or the administrators travelled, some of the scribes accompanied them (MTB, 418, 555); sometimes scribes were also used as messengers (MTB, 286).

During their travels, notaries were primarily required to correctly interpret the Order’s letters to the recipients and ensure that the reply letters were composed correctly. This is documented, for example, for the notary Nikolaus Berger, who was twice (1404 and 1407) part of the delegation to Lithuania (ARMGART, p. 260).

The scribes received clothing (MTB, 543) and accommodation (they lived on the ground floor of the palace; the sources mention scribes’ halls (AMH, 361) and scribes’ chambers (SRP 4, 119, 172)), but not a fixed annual salary; instead, they were paid according to their work results. This is evident, for example, from a letter from the mid-14th century scribe Matthias, who complained about the poor working conditions in the Marienburg chancery. This also included a complaint about the meager pay, as Matthias allegedly received only 1 cattle for every 20 pages written (GÜNTHER 1917; MENTZEL-REUTERS, p. 253f; JÓŹWIAK/TRUPINDA 2011, p. 238). The MTB contains several entries on payments to specifically named scribes who prepared deeds of gift (MTB, SS. 163, 185, 430, 468, 505). However, the amounts indicated there were quite significant; they varied from 2 to 10 marks.

Unlike simple journeymen copyists, such as the above-mentioned Matthias, most notaries held canonical or parish offices, which provided them with a decent income. The situation in the Warmia Chapter is also worth mentioning. The ordinance from around 1470 provides precise information on the remuneration of scribes depending on the type of document – letter, protocol, deed, as well as the use of a seal (SRW 1, 320; FLEISCHER, S. 805). Chief scribes/notaries usually received additional financial support through church benefices. In Prussia these were either canonries or parishes, both in the larger towns (Stephan Mathy, Ludwig von Erlichshausen's chief scribe, was parish priest in Elbing. He was one of the last faithful who remained with the Grand Master in the palace until they were forcibly expelled by Bohemian mercenaries in 1454 (SRP 4, p. 172). Paul von Molnsdorf, notary 1344-1348, became parish priest of St. Mary's Church in Danzig only after leaving the chancery (ARMGART, p. 231). Paul Winckelmann, notary in 1409-10, is later recorded as parish priest in Riesenburg (ARMGART, p. 269).) and in the villages (Johannes Schwarz, notary 1389-1392). years, administered the parish in Lesiewitz (ARMGART, p. 244), Andreas Lobner, notary 1389-1394, was the parish priest in the village of Schönberg (ARMGART, p. 246). Nikolaus Berger, notary 1400-1409, received the parish of Marienau in 1407 (ARMGART, p. 260). All these places were located in the vicinity of Marienburg. Presumably, the notaries collected the parish benefices to which they were entitled, but the actual pastoral duties were carried out by the vicar). Some notaries were subsequently able to occupy higher positions in one of the cathedral chapters of Prussia, and in one case a high-ranking notary even became a bishop - Johann of Meissen in 1332-1334. notary master, was bishop of Warmia in 1350-1355 (ARMGART, SS. 210-214).

Some scribes were given substantial "severance pay" when they left the office of the Grand Master. For example, the scribe Gregorius received 30 marks as a parting payment in 1408 (MTB, p. 507), and Nikolaus Berger even 50 marks in 1409 - "item 50 m. her Niclos Berger des meysters schryber, als her von hofe zoch" (MTB, 547). The Master's notaries usually held this position in Marienburg for only a few years. This can be explained, firstly, by the high qualification requirements that were imposed, which could only be met by having both many years of experience in the chancery service and an academic degree. Thanks to their work in the chancery of the Grand Master, many notaries were subsequently recommended for higher positions, so that service in the chancery often represented only an intermediate step on the career ladder.

The most studied biography of a notary master is that of Peter von Wormditt (NIEBOROWSKI 1915; KOEPPEN 1960; ARMGART, pp. 253–259), who entered the service of the Order as an apprentice at a young age (1376), studied in Prague in 1391, and was certified as a notary of the Grand Marshal in 1396. From there he moved to the chancery of the master in 1399, where he worked until 1402, during which time he made at least three trips to Rome. Finally, in 1403 he was appointed Procurator of the Order in Rome, a position he held until his death in 1419.

Also noteworthy is the life of Nikolaus Berger, who left the chancery of Marienburg in 1409, entered the monastery of Karthaus and was elected abbot in 1412 (ARMGART, SS. 261-263). Gregor von Bischofswerder, first a notary for the marshal, then in 1400 moved to the position of notary for the Supreme Master. After leaving the chancery in 1408, he worked as a parish priest in Konitsa, and in 1416 he was appointed chaplain to the master, which he remained until at least 1430 (ARMGART, S. 263-265).

An overview of verifiable notaries is given in ARMGART, SS. 200–271 (before 1410); see also the table of scribes/notaries in JÓŹWIAK/TRUPINDA 2011, SS. 231–233.

The Doctor (Arzt) and his Knecht

Presumably, with the establishment of a separate court in the 1330s, the Grand Master also received his own personal physician. Such a physician, Frigerius, an Italian, was first mentioned in 1333 (PUB 2, Nr. 777). The MTB contains a large number of records of physicians and their activities.

The personal physician received an annual salary from the master (Johann Rocque received an annual salary of 30 marks in 1401–1405 (MTB, 141, 199, 283, 342), his successor Nikolaus Birkhain received only 20 marks (MTB, 381), and the next physician, Master Bartholomeus Boreschau, received 70 marks a year in 1408 “Homeisters arzt: Man sal wissen, das man meister Bartholomeen jerlich 70 m. geben sal” (MTB, 476) and clothing. Physician Johannes received a skin every winter (MTB, 182, 276).

The physician also had a knecht - the knecht of the physician Master Johann Rocque is mentioned in the MTB in 1405 (MTB, 353).

Due to the nature of his service, the personal physician was constantly at the Master's side and accompanied him on his travels. In 1406, the Master's physician Nikolaus Birkhain took the Grand Master's necessities from the pharmacy when he was preparing to take part in the winter rais (MTB, 393). However, it is unclear from the sources where the physician's chamber was located.

The intensity of the personal physician's activities was also related to the health of the master. If he was healthy, the physician could be temporarily absent from Marienburg to help other patients. Thus, it is known from the MTB that the master's physician Johann Rocque traveled quite a long way to Brandenburg Castle in August 1400 to take care of the commander there - "2 m. magistro Johanni dem arzte geben, als her zum kompthur ken Brandinburg zoch" (MTB, 82). In addition, he treated the master, the treasurer, and the commander Tuchel (MTB, 283). In 1409, the physician of the Supreme Master Bartholomew even traveled to the Polish archbishop (MTB, 563).

However, in the event of the Master's illness, a second physician could be consulted. In the last years of his life, Conrad von Jungingen frequently suffered from health problems, which is reflected in the MTB by several entries on the purchase of medicines (MTB, 353, 380, 383, 393f, 418). In 1404, a second physician was called from Danzig to the ill Grand Master (MTB, p. 308). Presumably, this was Nikolaus Birkhain, who was called several times to the bedside of one of the stewards during this period (MTB, 338, 365). In 1405, he traveled from Danzig twice to see the Master when the latter fell ill while traveling, once to Leipa (MTB, 366) and once to Christburg (MTB, 387). In 1406/07, he officially served as physician to the Grand Master. In January 1407, when Conrad von Jungingen was already seriously ill, the Grand Marshal wrote to the Grand Master about a meeting with the Master’s physician, Bartholomeus, to whom he informed him of the Master’s illness. The Marshal advised Conrad to take Bartholomeus as a second physician, since the advice of two physicians would be more useful than that of one (CEV, 141). This was Bartholomeus Boreschau, then Dean of the Ermland Cathedral Chapter, who was appointed physician to the Master in 1408 (ŚWIEŻAWSKI; PROBST, p. 162f; JÓŹWIAK/TRUPINDA 2011, p. 263). Boreschau was accused of treason by Heinrich von Plauen during the siege of Marienburg in 1410 and left Prussia (CUNY, SS. 146–151). He returned to Warmia no later than 1420 and became known above all as the donor of a very high-quality panel to the Frauenburg Cathedral.

In addition, in emergency cases, medicines were obtained from renowned physicians abroad. In 1406, the procurator of the Order from Rome sent Konrad von Jungingen a medicine prepared by the famous physician Johann Theodorus (VOIGT GESCHICHTE PREUSSENS 6, p. 375). An explanatory letter from Theodorus has been preserved for this batch of medicines - a detailed list with instructions for taking the various powders, as well as additional dietary advice. The doctor's letter indicates that the remedy was intended primarily for the treatment of stone disease and gout (SCHOLZ 1959).

In the last years of his life, Konrad von Erlichshausen was also served by two physicians, Jacob Schillingholz and Heinrich Pfalzpaint (OBA, no. 28323; JÓŹWIAK/TRUPINDA 2011, p. 264f). In 1449, the Jewish physician Magister Meyen from Nessau in Poland was even called in to treat the Grand Master (PROBST, pp. 163–165; JÓŹWIAK/TRUPINDA 2011, p. 265f). In 1417, the personal physician of the Hungarian king was to be appointed physician to the new Grand Master. The annual salary was set at 200 florins, and the physician was promised court clothing, good food, and fodder for four horses (VOIGT GESCHICHTE PREUSSENS 6, p. 451).

There was no apothecary in Marienburg. Therefore, when necessary, the doctor went to the apothecary in Danzig (in 1406, the doctor Birchayn brought medicines from the apothecary in Danzig - "item 41⁄2 m. meister Birchayn vor apoteke unserm homeister, als yn meister Bartholomeus ken Danczk dornoch sante, und vor syn ungelt" (MTB, 383). In 1407, the doctor Birchayn sent the cornmeister to the apothecary in Danzig (MTB, 418) or Thorn (MTB, 283) for medicines for the Grand Master or brought them to him.

The physician's task was not only to look after the Master in case of illness, but also to ensure that his master led a healthy and sensible life. This can be judged from a very interesting source - a letter from the personal physician of the first half of the 15th century to the Grand Master with numerous dietary and behavioral recommendations (OBA, no. 28337; printed by HENNIG 1807. Since the letter is not dated or signed, its exact time of origin remains unclear. HENNIG 1807, p. 280, assumed the addressee to be Grand Master Conrad von Erlichshausen (1441-1449), while the editor of the GStA dates the letter to the time of Conrad von Jungingen. VOIGT 1830, pp. 189-191, mentions this letter, which has not yet been assessed in the research literature). This letter not only details what foods and drinks would be beneficial to the Master's health and what should be avoided. The physician also gives advice on how to prepare food, and when, how, and in what quantities. There are also recommendations for physical exercise, such as exercising before meals and warming up the body, but refraining from physical exercise after meals so as not to disrupt digestion. There are also psychological tips, such as the physician's advice not to go to bed at night with the day's worries on his mind, or to call in jesters, a dwarf, and minstrels if the stress of work is too great, to entertain the master with their play and distract him from the stress of everyday life. It is clear from the letter that the physician was well acquainted with the circumstances of the Grand Master's life, and the medical advice shows genuine concern for the Master's well-being.

On personal physicians, see PROBST; MILITZER 1982; JÓŹWIAK/TRUPINDA 2011, pp. 262–266.

Dieners of the Supreme Master (Diener)

The Master's servants formed a separate and distinct group at his court. They were mainly young noblemen who joined the court of the Grand Master for a certain period of time, without being or wishing to become knights of the Order. Among the servants were people from the small feudal estates and lower noble families of the empire, as well as from Poland and Lithuania, the patricians of the Prussian cities and Prussian nobles.

Several letters of recommendation from German princes to the Grand Master have been preserved, asking him to accept young lords as his diners (JÄHNIG 2002b, pp. 37–40). Young noblemen, members of the nobility, often pledged themselves to serve the Master for one or two years in order to get to know the country, politics, and administration of the Teutonic Order better. The court of the Grand Master apparently had a particularly good reputation among the nobility of the Holy Roman Empire (JÄHNIG 2002b, p. 38) and was therefore in great demand as a “training ground” for young nobles.

Sometimes the young men came from non-German countries and were required to learn German during their stay in Marienburg (JÄHNIG 2002b, p. 25, 40). The Grand Master may also have benefited from the presence of the young nobles, since some of them later rose to influential positions and offices. The connection with the Teutonic Order that arose as a result of the stay in Marienburg may have been advantageous for political relations. This benefit for the Master apparently led to an increase in the number of foreign diners compared to local ones, which the Prussian estates criticized in 1438 and 1440 and demanded a reduction in the proportion of foreigners (SRP 4, 111; JÄHNIG 2002b, p. 38).

Some of the diners, however, remained in the Grand Master's retinue for many years, for example Nammir von Hohendorff first appears in the MTB in 1400 as a diner (MTB, 68) and only goes on leave in 1408 (MTB, 510). In some cases, a diner even served for life, as is recorded in the case of Jacob Osterwitt, who was awarded quarters with a fireplace and a table laid according to a doctor's prescription for his faithful service until his death in 1446.

On June 20, 1446, the Grand Master granted the Master's steward Jacob Osterwitck, for his faithful service, a room with a fireplace near the Chapel of St. Lawrence, where he was regularly provided with firewood for heating. He also had the lifelong right to dine and drink daily with the half-brothers. If he fell ill or became so infirm that he could no longer come to the table, he was given food and drink in his room. Jacob was allowed to keep a boy, who was entitled to three loaves of bread a day, but otherwise the owner had to provide for him. Jacob was given clothing, shoes and other necessities, as was proper for half-brothers. Finally, he had the right to freely bequeath his property by will. (GStA, OF 16, p. 124f; printed version: NOWAK, p. 148f.)

At the beginning of the 15th century, there are several lists in which the total number of diners is given as 13 to 20 people (JÓŹWIAK/TRUPINDA 2011, p. 256). They were supposed to be in close proximity to the Grand Master at all times and accompany him on trips. The diners were also supposed to gain military experience and took part in Lithuanian campaigns. In 1405, the MTB records that six of the Master’s diners took part in a winter campaign in the retinue of the Grand Commander: “item 19 m. of our homeisters dynern iren sechsen als Nammir Sparaw Johan Westerstete Olbrecht und Kunczen” (MTB, 340). Individual diners could be entrusted with minor tasks or (if they were more experienced) diplomatic missions. They then set out on trips throughout Prussia and abroad, either on their own or together with territorial officials or guests (MTB, 17, 20, 68, 359, 404, 458, 460, 467, 478, 508, 540, 543, 551, 560; AMH, 114).

Perhaps the diners were supposed to serve the master and his guests at a court banquet.

The diners were supported by the master, and received clothing and lodging (MTB, 82, 431, 466), but not an annual salary. Young foreign nobles who came to the master as diners for only a very short time sometimes did so entirely at their own expense. This is evident, for example, from the petition of Heinrich von Schönburg in 1449, who wanted to serve the Grand Master for no more than six months and agreed that he would ask for neither money nor salary. The master, however, acknowledged that Heinrich’s servants and horses would be cared for in Marienburg (JÄHNIG 2002b, p. 40f).

When the diner left the service, they were usually paid a large sum and often given a horse (MTB 40, 81, 347, 400fd, 486, 500, 510, 537, 540, 562). There are several records of the Grand Master financially promoting and sponsoring the marriages of diner (MTB, 68, 150, 416). Married diner of the Grand Master rented their own apartment in the city. Some of the master's diners had chambers in the castle (the chambers of diner Petreš (AMH, 32), diner Kirstan (AMH, 77)), but there were also rooms of diners in which several young noblemen lived together (AMH, 73, 114, 140, 241; JÓŹWIAK/TRUPINDA 2012, p. 207f).

On the diner, see SRP 4, 110–114, note 4 (Max Töppen’s explanation in the preface to the History of the Prussian Confederation); KLEIN, pp. 71–74, 170f; WENSKUS 1970, p. 364f; JÄHNIG 1990, p. 61f; JÄHNIG 2002; JÓŹWIAK/TRUPINDA 2011, pp. 253–257; JÓŹWIAK/TRUPINDA 2012, pp. 203–208. On the diner of the Prussian bishops, see JARZEBOWSKI, pp. 244–247.

Master Builder (Baumeister)

The Grand Master had a building expert in his service, who professionally supervised the building projects of the Order's headquarters, designed smaller buildings himself, and sometimes also worked as a mason or stonemason in individual castles. So far, only one example of such a "master builder" can be found in historical sources. This is Nikolaus Fellenstein, who is often mentioned in the account books between 1400 and 1418.

On 15 January 1400, the Grand Master concluded an agreement with a mason, presumably from Koblenz, according to which Fellenstein received an annual salary of 20 marks and clothing. In addition, he was entitled to a travel allowance, and when he worked as a mason, he received a corresponding salary. However, evidence of masonry work is rare. For example, at Grebin Castle he apparently supervised the masonry and cut the stones himself (MTB, 212). And there is little evidence of his own building plans – he supervised the construction of the tower in Marienburg (SCHMID, p. 83; HERRMANN, p. 135f; JÓŹWIAK/TRUPINDA 2011, p. 83).

Most of the entries in the accounts relate to Fellenstein's missions to castles and courts throughout the Order's territory (Bütow, Grebin, Kaldenhof, Kishau, Königsberg, Leipe, Memel, Papau, Ragnit, Roggenhausen, Sobbowitz, Strasbourg, Stumm and Tilsit), where he inspected building sites, carried out repairs, paid workers or purchased building materials on behalf of the Grand Master. Since he was married and a citizen of Marienburg (SCHMID, p. 83), he probably lived in the city rather than in the castle. Whether the function of a master builder (not to be confused with the position of stone master, which was held by a brother of the Order and who was mainly involved in the management and procurement of building materials (JÓŹWIAK/TRUPINDA 2015)) already existed in the 14th century cannot be determined from the surviving written sources. However, the intensive building activity of the Order at this time rather suggests that the Master hired a building expert at his court already before 1400, which allowed him to exercise a certain amount of supervision and control over the Order's building projects in Prussia.

In 1407/08, a "worker" appears in the MTB (MTB, 428: "werckmanne", elsewhere called "buwmeister" (MTB, 430), apparently a specialist in the construction or operation of salt works, since he traveled several times to an unspecified "Salzwerg" and also took tools from there (MTB, 458). This was a monk from Koblenz named Friedrich (in the MTB he is several times called a "Rhine monk"), who came to the General Chapter in 1407 with a delegation from the Komtur of Koblenz (MTB, 428). This monk remained in the service of the Master, together with his servants, until 1408 and received a salary and clothing (MTB, 430, 495f). This worker was apparently a specialist who was admitted to the court of the Grand Master only for a short time to carry out a specific task.

Court painter (Hofmaler)

As with the master builder, we know from written sources of only one court artist of the Grand Master. This is the artist Peter, who appears in the MTV between 1398 and 1409. He probably entered the service of the Master before 1398 and is last mentioned in 1414 (AMH, 128). The accounts show the wide range of his activities: he produced frescoes (in the winter remter, the remter of the Convention, the chapel, the Master's room and the Grand Commander's room - MTB, 158f, 216, 272, 318, 402), panels (MTB, 318, 402, 467), book illustrations (MTB, 155), painted altars (MTB, 64, 318), organ cases (MTB, 342), banners (MTB, 21, 69, 103), flags (MTB, 103, 216, 313, 384, 554, 588), shields (MTB, 179, 216, 318), coats of arms (MTB, 384), clock dials (MTB, 112), tent tops (MTB, 63, 216, 554, 588), lanterns (MTB, 21, 216, 318) and birdhouses (AMH, 128).

Peter worked mainly in Marienburg, but was also sent several times to other castles, such as Memel (MTB, 5), Ragnit (MTB, 342, 442) and Neidenburg (MTB, 318). Like the master builder, Peter the painter was a secular craftsman and was married. He was probably also a citizen of Marienburg and lived in the city. There is no information about an earlier court painter, but it can hardly be assumed that Peter was without predecessors. The wide range of activities described above shows the need for an artist for the court of the Grand Master. The artist was often busy applying his master's coat of arms to the many banners, flags, shields, lanterns and tents - a process that did not necessarily require artistic effort, and which the masters experienced more and more often, beginning with Luther of Brunswick.

For the court artist, see VOIGT 1830, SS. 236-238.

Heralds

Heralds played a special role for the Teutonic Order, as they arrived in large numbers in Prussia together with the guest knights during the Lithuanian campaigns. The interest of these specialists in the coats of arms and honours of nobility, as well as in the history and course of medieval wars, lay in their concomitant participation in the crusades against the Lithuanians. In this context, they also had a special task: the selection of participants for the "Table of Honour" - an institution that existed only in Prussia, where (similar to the legendary Arthurian Round Table (PARAVICINI 1989, p. 324)) only the most respected and brave knights were admitted.

The Lithuanian campaigns and tables of honour, it is true, took place far from Marienburg, but numerous heralds were also invited to the residence of the Grand Master. For example, an analysis of the MTB for 1407/08 shows that the Grand Master presented gifts to 14 foreign heralds for their services during this period (MTB, 417f, 428f, 434, 440, 467, 469, 473f, 476, 479, 495, 505). Thus, the number of heralds was greater than all the other invited minstrels, orators and wanderers combined. Some heralds came accompanied by foreign delegations. In 1405, two heralds who were part of the delegation of English envoys stayed in Marienburg - "item 2 m. "These are the heralds who wore them with the Engelant's orders" (MTV, 359). Some of them may have remained in Marienburg for a longer period of time and were temporarily part of the court. From time to time they carried out important tasks for the Order. Famous was the presentation of two swords to the Polish king and the Grand Duke of Lithuania before the Battle of Tannenberg in 1410 (BOCK, p. 271). This presentation of the swords was made by the herald of the Holy Roman Empire and the herald of the Duke of Stettin, guests of the Master.

During the 14th century, the heralds' activity became institutionalized as a kind of office, so that every ruler had at least one herald in his service, who, as his representative, often proclaimed the sovereign's glory in foreign lands. This is evidenced by the large number of foreign heralds recorded in Marienburg. The Grand Master naturally had one or more heralds, who also regularly went abroad to represent the Order. Thus, the Kings of Heralds of Prussia first appear in the registers of the courts of the County of Hainaut as early as 1341 and 1344 - one of the earliest records of German heralds (BOCK, p. 401). From the title "King of Heralds" one can conclude that there were already a larger number of heralds in Prussia at this time. However, some of these heralds probably still belonged to the wandering people and were not servants of the Teutonic Order.

The earliest herald of the master whose name can be established is Bartholomeus Lutenberg, mentioned in 1388 (PARAVICINI 1989, p. 331). Lutenberg delivered the letter of the master to the English king in 1388 (VOIGT GESCHICHTE PREUSSENS 5, p. 526; GERSDORF, p. 199). He was succeeded by the most famous herald, Wigand of Marburg (SRP 2, 429-452; VOLLMANN-PROFE; BOCK, p. 310f), who, according to his own account, served Conrad of Wallenrod (1391-1393) and wrote an extensive rhymed chronicle of the wars of the Teutonic Order (especially the Lithuanian campaigns) between 1294 and 1394. Wigand probably later changed his “employer” and appeared again in Marienburg at the turn of 1408/09 – this time as a guest (MTV, 524).

Other heralds known by name are Michel Gotthein or Holthein (PARAVICINI 1989, p. 331f), mentioned in 1419, and a herald named Prouschen/Prussia (PARAVICINI 1989, p. 332; BOCK, p. 151, 404), who is mentioned several times in documents between 1439 and 1444 (also in the Empire).

Almost nothing is known from the sources about the details of the heralds' activities. It is known that Wigand of Marburg was an active writer. The literary form of the rhymed chronicle was undoubtedly intended to be read aloud, presumably both to the knights of the order and to guests. It can be assumed that the herald himself read his poems. What other services he provided can only be assumed.

It is obvious that he had no fixed annual salary, since heralds received their livelihood from gifts. The herald, of course, received a service robe with the coat of arms of the order, but nothing is known about his quarters.

As regards the distinction between herald and jester, it should be noted that there were transitional forms in the Grand Master's retinue. For example, between 1400 and 1403, the MTB mentions Nünecke several times, who is first described as a herald (MTB, 72, 126, 260) or a herald (MTB, 118), but from 1404 onwards he appears as the Master's jester, equipped with a belt with a bell and a white mantle (MTB, 285, 321, 363, 404). He was apparently originally a travelling herald who often performed in Marienburg and who probably pleased the Grand Master so much that he eventually took him into his service as a court jester.

On the heralds in Prussia and Marienburg, see BOOCKMANN 1991, SS. 221-224; JÓŹWIAK/TRUPINDA 2011, SS. 305-308. The foundation stone for the herald system is the book by BOCK, who also discusses the heralds of the Grand Master (SS. 137, 139-142, 147, 151, 310f, 401, 404).

Jester (Narr)

The Grand Master also had a jester at his court, but little is known about his activities. More detailed information is known only about two jesters: the first is the aforementioned Nüneke, who is first attested as a herald in Marienburg in 1400, and then transferred to the position of jester in 1404 (MTB, 285) and is documented until 1406 (MTB, 404). In 1428, the Master's jester Henne is mentioned, who was sent to the court of Grand Duke Vytautas and wrote a letter from there to the Grand Master (CEV, Nr. 1329). This letter, however, does not have any humorous content. Henne mainly reports on his journey through Lithuania from Trakai to Smolensk, sharing – almost like a spy – various information about the living conditions at the court of the Grand Duke. Henne occupied a hybrid position between knight and jester, as evidenced by his signature on the letter: "Henne, vormittage ritter nachmittage geck, euwer hovgesinde" (CEV, Nr. 1329).

From Lithuania, the knight-jester moved to Livonia. This is evident from Vytautas' letter to the master, which was written a week after Henne's letter (CEV, Nr. 1330). In it, Vytautas somewhat ridicules the ambitions of Henne, who no longer wanted to be half a jester (Hecke) and half a knight, but only a full knight. For this reason, Henne rejected Vytautas' letter of recommendation, because in it he was also called a jester (CEV, Nr. 1330). Henne referred to the master's letter, in which he was only called a knight. Despite these knightly ambitions, he apparently still entertained the Grand Duke with funny jokes, since Vytautas confirms in his letter to Paul von Rusdorf that Henne "showed us many ridiculous jokes." In another letter, Vitovt told the Grand Master how to bring Henne to his senses, “if he no longer wants to be ridiculous.” The Grand Duke recommended giving the arrogant fool two good slaps in the face so that he would become obedient again (VOIGT 1824, p. 334f).

Even the little-known information about the two chief jesters suggests that they were complex individuals who moved from one profession to another. They were educated (Nyneke started out as a herald, and Henne wrote letters in his own hand), traveled widely, and were quite self-confident, as evidenced by Henne's almost arrogant behavior toward the Grand Duke of Lithuania.

"Jester knights" also existed at other courts and sometimes came to Marienburg. For example, an (undated) letter of recommendation from the Margrave of Brandenburg has been preserved, in which he sent Hans von Kronach, "the dishonest knight of all good deeds" who belonged to his court, to the Grand Master and asked the Master to accept the "Knight of Fools" for a while (VOIGT 1830, SS. 187-189).

Minstrels and Trumpeter (Spielleute und Trompeter)

Most of the minstrels whose performances are recorded in the MTV or other sources were musicians from out of town, hired by the Grand Master for a specific occasion or who came to Marienburg as travelling artists to present their art. In particular, musical performances were given at general or provincial chapters, as well as at meetings of the council of territorial authorities and at bishops' consecrations, in which the master's minstrels often worked together with foreign musicians to form a large ensemble. The largest ensemble was assembled for the chapter of 1399, when 32 minstrels performed together - "item 16 gelrelysche guldyn den spilluthen gegeben zum capitel, am dinstage noch senthe Niclus tage; Pasternak nam das gelt und der spilluthe woren 32" (MTV, 41).

There are also accounts of minstrels performing at chapters, territorial assemblies and episcopal consecrations (MTB, 86, 196, 269, 314f, 505). There are references to fiddlers performing during the visit of guests, for example in 1400 in honour of Grand Duchess Anne (MTB, 316) or in 1405 when English ambassadors visited the Grand Master (MTB, 359).

On the other hand, the number of permanent minstrels employed by the Grand Master was small. In the period covered by the MTV (1398-1409), only two musicians are mentioned who belonged to the court staff: the minstrel Pasternak and his apprentice Hensel (BOOCKMANN 1991, p. 222f.). Both received an annual salary (MTB, 160 (1402) - "item 6 m. Pasternag und Henseln des meisters spilluten gegeben"), donations (MTB, 415), court clothes (MTB, 482, 528) with the coat of arms of the Supreme Master (in 1401 a jeweler made a coat of arms of the Master for Pasternak and Hensel, which the two minstrels wore on their court clothes - MTB, 102; after Ulrich von Jungingen took office in 1407, coats of arms of the new Master were made for the two minstrels, this time, apparently, from precious metal, since the jeweler received a solid sum of 20 marks for them, MTB, 458), horses (in 1399 Pasternak and his kumpan Hensel received a horse - "item 4 m. Pasternak and Hensil used a lock to lock the door of the guard at Niclus's (MTV, 40) and the chambers, in 1416 a lock with a key was made for "des meyster spelman", which was probably intended for his chambers (AMH, 224).

The instruments the two minstrels played are not specified in the reports. Only once is Pasternak named as the master's fiddler (MTB, 482). It is possible that Pasternak and Hensel played different instruments, perhaps even the organ in the master's chapel, since the sources do not mention a specific organist.

The minstrel's duties also included looking after the foreign musicians who appeared in Marienburg on the occasions already mentioned. In the MTV he is sometimes mentioned as the one who received the money to pay the various minstrels (MTV, 41, 468, 505). He probably also led the musical ensembles that were formed to provide musical accompaniment for major events.

In addition to the two minstrels, there was also a trumpeter, but he is mentioned only once. His chambers were in the basement of the palace, next to the living quarters of the chancery clerks. The History of the Prussian Confederation reports for 1454 that a fragment of a cannonball that exploded on the stone bridge flew into the trumpeter's chamber (SRP 4, 119).

The trumpeter had a special function among the minstrels: he sounded fanfares at public events and ceremonies. The gallery above the main portal to the summer refectory probably also served this purpose.

On the activities of foreign minstrels and artists, see Chapter 11.2.4. On music at the court of the master, see ARNOLD.

Cripples (Krüppel)

The Grand Master had a group of people in his service who are described in the account books as "cripples". However, what their disability was is not stated directly. Presumably, they were dwarfs, but not physically or mentally disabled. The entries in the accounts show that they carried out a large number of rather important tasks for the Grand Master (some of them diplomatic in nature), which could not have been carried out without physical and mental health. They carried out small monetary transactions on behalf of the treasurer and the master (MTB, 30, 45, 51, 100, 105, 111, 458, 495, 515, 519, 544, 554), accompanied guests and territorial administrators on trips around Prussia or abroad (MTB, 340, 478, 490, 548), brought horses to various cities of the Order state (MTB, 357, 467) or presented gifts to foreign rulers (MTB, 424, 430, 525).

The cripples received wages (MTB, 70, 202, 458, 514) and gifts (MTB, 179, 415, 467, 524), clothing (MTB, 86, 126, 525), shoes (MTB, 325), weapons (MTB, 265), horses (MTB, 419) and bridles (AMH, 109, 265, 360). One of the cripples was even named a knight - "Jorgen dem kropelritter" (MTB, 415, 460).

During the period covered by the MTV (1398-1409), the group of cripples consisted of five people, among whom the most important was apparently Nikolaus Kropil, since he was mentioned more often than others and carried out many different tasks for the master and received an annual salary of 5 marks (JÄHNIG 1990, p. 572). In 1420, a cripple was mentioned whom Vitovt sent to Marienburg (CEV, Nr. 901).

The cripples wore a white garment consisting of a chausse (MTB, 526), a tunic (MTB, 20, 404, 461, 495) and a hood (MTB, 19, 578). Thus, in appearance they resembled a court jester, but did not have bells.

Presumably, in addition to the many serious official duties they had to perform, they also contributed to the entertainment of the Master and his guests. This is indicated by a passage from a letter from a personal physician, in which he recommends to the Grand Master that when worries get out of hand, he should call upon cripples or minstrels to come to him, so that they could lead him to other thoughts with their cheerful gestures (HENNIG, p. 287).

Nothing is known about the wards and the location of the cripples' beds.

On cripples, see BOOCKMANN 1991, p. 219; JÓŹWIAK/TRUPINDA 2011, pp. 249-251.

Witinge

There is also evidence of the presence of Witings (servants of Prussian origin) in the entourage of the Grand Master. Witings were Prussian nobles or freedmen, mainly from Samland, who remained loyal to the Order during the Second Prussian Uprising (Witingeprivileg of 1299 - PUB 1/2, no. 718).

The vitings served the Order primarily in the castles of the northern commandries. In 1409, the MTB mentions the payment of money to the Master's vitings (MTB, 577). However, it is impossible to say exactly how many vitings were in the Master's retinue. The MTB mentions various vitings by name, but it is not always clear whether they belonged to the Master's personal entourage. The most frequently mentioned viting is Vogelsang, who carried out a number of orders for the Grand Master between 1400 and 1406. He accompanied the messenger of the Grand Duke of Lithuania from Marienburg to Thorn (MTB, 74), brought the Grand Master's silver and wine to Thorn (MTB, 111, 174), transported provisions and horses to the castle construction site in Ragnit (MTB, 185, 400) or money to Königsberg (MTB, 369).

On the Vitings in general, see WENSKUS 1986a, SS. 432–434; VERCAMER 2010, SS. 165f, 257, 294–296; KWIATKOWSKI 2012, SS. 366–391.

Washerman (Silberwäscher)

The MTB repeatedly mentions a “silver washer” (MTB, 8, 20, 140f, 224f, 341, 380, 415, 466, 508, 578; JÓŹWIAK/TRUPINDA 2011, p. 246f), whose main job was apparently to wash the Grand Master’s clothes. For this he received (in addition to his annual salary of 4 marks – JÄHNIG 1990, p. 71) a fee for washing and money for soap. Whether he was also responsible for the care of the Master’s silverware is unknown, but he at least guarded it at night, since his bed was probably in the silver chamber (AMH, 247), located between the Master’s living room and his chapel.

The washerman also accompanied the master on his travels. In 1409, the washerman Thomas washed the master's laundry during his stay in Thorn (MTB, 578). His work was obviously not easy, as the turnover of workers was quite high. Between 1399 and 1409, at least four different people worked successively as the master's washerman: Hannus (1399), Michiel (1403), Niklus (1405/08), and Thomas (1408/09).

Gatekeeper

The term "gatekeeper" appears only once in 1430 (GStA, OF 13, p. 583; JÓŹWIAK/TRUPINDA 2011, p. 246). This term is probably similar to the term "gate guard". In the account books between 1406 and 1411, the master's gatekeeper Hans is mentioned several times (NKRSME, p. 93; MTB, 415, 432, 467, 499, 519, 524, 532, 558; AMH, 3, 9, 306; JÓŹWIAK/TRUPINDA 2011, p. 245f).

He lived under the roof of the building north of the chapel (AMH, 306), which in 1410 is called the gatekeeper's house - "Hans thorwert huses" (AMH, 3). The guardroom must therefore have been located on the ground floor of this building. All visitors who wanted to enter the palace through the main portal probably had to come here. Sometimes it was also possible to deposit or pick up things here. For example, in 1409, the accounts twice note that the gatekeeper received money intended for other people. At one time, this was 10 marks in small coins, which were to be distributed to the poor on the feast of Corpus Christi (MTB, 519). In the second case, Hans took 2 marks for Lord Tyrold from Strasbourg (MTB, 532). In 1408 it is recorded that the Grand Master lost 4 cattle in a game, and the gatekeeper Hans received the money (MTB, 499). Perhaps the master was playing checkers or chess with his gatekeeper at the time.

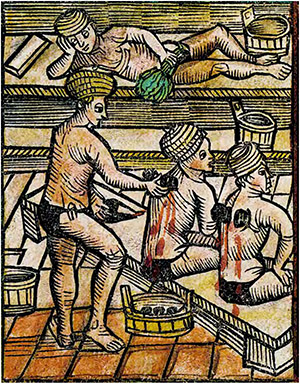

Bath attendants (Bader)

According to the entries in the MTB, both Grand Masters of Jungingen liked to wash frequently. They had their own bathhouse at their disposal, which was located in the forecourt of the palace and was run by the bathhouse attendant Peter. When the Grand Master traveled, he used the bathhouses in the towns along his route. The MTB contains numerous entries about payments to bathhouse attendants in the towns of Danzig (MTB, 118), Stumm (MTB, 202), Mirchow and Leske (MTB, 403), Stargard (MTB, 498), Schönsee (MTB, 590), Rehden (MTB, 578). In the countryside, the Master entrusted the heating of the bathhouses to servants or a bathhouse attendant, as in Büsterwald (MTB, 487), Hammerstein (MTB, 499), Schwetz (MTB, 499), Tuchel (MTB, 535). When the Grand Master travelled in 1405, one-off expenses for bath attendants are recorded (MTB, 367), and he was sometimes accompanied by his own bath attendants – in 1408 the barber Peter received money when he accompanied the Master on his journey to Kovno (MTB, 459). Peter received an annual salary (MTB, 515), clothing – in 1408 he was given a doublet (MTB, 467), and in 1409 a tunic (MTB, 537) and money for house rent (MTB, 467, 496). From the latter, one can conclude that he probably lived in a rented house in the city.

In addition to heating the water and washing, the bath attendant's duties included obtaining branches to prepare bundles of leaves for the bathers to cover or fan their skin with while bathing (AHM, 359). It is possible that the bath attendant also worked as the master's barber and carder, since these hygienic and medical tasks were part of the bath attendant's general responsibilities (TUCHEN, p. 31; BÜCHNER, p. 26f).

Stoker (Stubenheizer)

The palace had four stoves for hot air heating and an unknown number of tile stoves. In addition, there was a large hot air stove under the Great Remter. Heating these stoves was the job of a stoker, who received an annual salary from the Grand Master (MTB, 19, 82, 179; AMH, pp. 4, 21, 130, 186, 281, 334, 358) and clothing (MTB, 509). Further information about the life and work of the stoker cannot be obtained from the invoices. He undoubtedly slept in a room in or near the palace, since his work required a permanent presence in the building during the winter.

Shield bearer (Schildträger)

According to the provisions of the eleventh custom of the Order, the master was entitled to a shield-bearer (PERLBACH, S. 98). In documents, a shield-bearer appears as a witness only once in 1372 (REGESTA 2, Nr. 988). Further references to his activities are unknown.

Messengers and runners (Läufer und Boten)

The enormous growth of written communication in the 14th century meant that letter transport became increasingly widespread. Various groups of people were used to carry letters for the Grand Master at home and abroad: religious figures, chaplains, priests, servants, scribes, falconers, cripples, knights and even apprentices, who were said to have served as messengers. There were also messengers who specialized in delivering messages. In 1392, a messenger named Nikel is mentioned who brought letters to the Grand Master from the Order's procurator in Rome (LUB, Nr. 1588). In 1404, the MTB mentions a messenger named Nikolaus Panne who was sent by the Master to the King of Rome (MTB, 305). In 1409, the runner Panne is mentioned, this time carrying letters to the Landmeister of Germany (MTB, 560f). Jacob Grüneberg appears in the reports as a second runner. Several times in 1403-4 and 1409, he carried letters from the Master to Rome (MTB, 234, 273, 320, 561), which is why he was also called the "Roman Huntsman" (MTB, 469), as well as to Austria (MTB, 384), Bohemia (MTB, 469) and Germany (MTB, 359, 451). In the first decade of the 15th century, the Grand Master employed at least two runners who made exceptionally long journeys with messages to the German lands and Italy.

Written sources do not provide any information about the circumstances of the life and work of the fast walkers. In their activities, they only occasionally stopped in Marienburg.

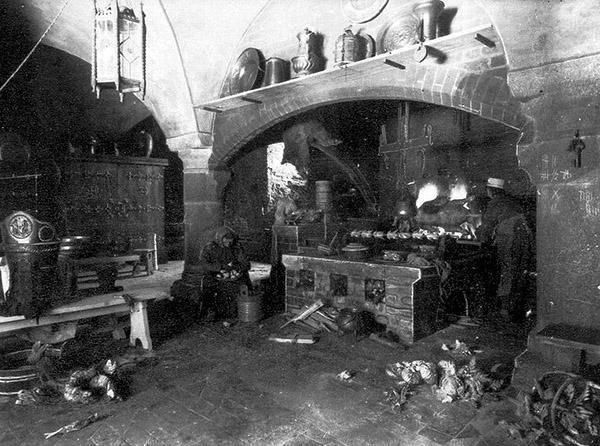

Kitchen Master (Küchenmeister)

The position of kitchen master was held mainly by knight brothers, sometimes also by priest brothers. The kitchen master supervised the work of the Grand Master's kitchen, supervised the work of the kitchen staff, and paid them their wages. According to the Ordination of Heilsberg Castle, the kitchen master of the Bishop of Warmia had the right to punish the kitchen workers if they entered the kitchen without permission or stole food (SRW 1, 329; FLEISCHER, p. 814). A similar situation may have existed in Marienburg. In 1417, the master received a salary for the cooks, the amount of 20 marks (AMH, 289). In 1412, it is recorded that the kitchen master received money to pay the wages of the kitchen servants (AMH, 40). In addition, he was mainly responsible for purchasing and paying for food supplies. When the Master went on a journey, he was accompanied by the kitchen master and the cooks. In 1419, for example, the kitchen master and four cooks traveled with the master for 14 days – “item 16 sc. 4 kochen, di do 14 tag mit des meisters kuchmeister in der reisze gewest, yo di woche 2 sc.” (AMH, 321). In 1420, the kitchen master accompanied the master with five assistant cooks to the Day of the Estates in Elbing – “item 2 m. 2 sc. nuwes geldes 5 kochen, dy mit des meisters kochmeister uffem tage woren” (AMH, 360). However, he did not take direct part in the management of the kitchen, which was under the direction of the head cook.

For his work the kitchen master received a salary and clothing (MTB, 123, 191), he had a room with a fireplace and a toilet, which was located directly next to the kitchen.

On kitchen masters, see JÓŹWIAK/TRUPINDA 2011, p. 258f.

Senior and junior chefs of the master (Oberkoch)

The management of the kitchen was in the hands of the head cook, about whom almost nothing is known in written sources. The only documented evidence of a senior cook is in the account book of the old town of Elbing for 1407 (NKRSME, p. 93). The MTB mentions a cook of the master Matthys in 1409 (MTB, 524). He was supposed to receive a salary, clothing and housing, but there is no concrete evidence for this. His deputy was probably a junior cook (NKRSME, p. 93), about whom almost nothing is known.

Cooks and kitchen servants (Köche)

Several cooks worked in the Grand Master's kitchen, but their exact number cannot be reliably determined. If the Kitchen Master went with five assistant cooks to the Elbing Estate Day in 1420 (AMH, 360), there must have been at least three or four regular cooks. It is possible that cooks specialized in certain types of food. They were, of course, provided with clothing and accommodation, but there is no further information about this.

Two entries in the MTB are noteworthy, which mention a Russian cook (MTB, 471). Thus, he received a tunic in 1408, and a year later this clothing was hemmed, and the scribe notes that during this time the Russian was baptized (MTB, 531). Presumably, he appeared at court together with the Russian ambassadors, who brought falcons from Vitovt as a gift to the master and received a beautiful dress in return (MTB, 471). And the cook may have been part of this Russian delegation.

Knechts worked as kitchen assistants and were paid by the kitchen master (AMH, 40f, 84). Information on the number of knechts is unknown, as is where they slept. It is possible that they spent the night in or near the kitchen. Sleeping places for servants at the workplace were common. For example, the agreement between the Bishop of Warmia and the cathedral chapter regarding the use of the bishop's house in Frauenburg stipulates that kitchen servants and grooms were to spend the night where they worked (CDW 4, no. 32; JARZEBOWSKI, p. 111).

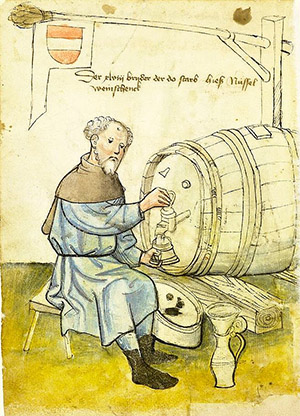

The cellar keeper (Kellermeister) and his boy

The cellar master was an official of the Order responsible for the supply of wine, beer and mead to the court of the Grand Master. Non-alcoholic drinks are mentioned very rarely, for example, the supply of cherry juice and mors in 1408 (MTB, 510). In addition, the cellar master belonged to a group of people who received money on behalf of the Master to carry out small transactions for him or to pay off others (MTB, 126, 140, 156-158, 167, 202, 233, 300, 473, 495, 585).

The convent house had a brewery, and the brewer and his knechts are frequently mentioned in the account book of the Marienburg Hauskomtur (AMH, 406).

The beverages were usually purchased in large quantities in Danzig, Elbing or Thorn (MTB, 150, 234f, 286, 298, 343f, 390, 422, 448, 456f, 477, 481, 520-522, 539; AMH 281, 357). They were stored in the cellars beneath the Grand Master's Palace and the Great Remter. Only the mead was sometimes produced by the cellar master himself. In 1407, he bought four barrels of honey on the occasion of the general chapter, in order to make mead from it - "item 12 m. vor 4 tunnen honigis des meisters kellirmeister, methe do von zu bruwen of das capitel" (MTB, 426). In addition, he took care of the dishes, glasses, cups, bottles, drinking pitchers and tablecloths (AMH, 11, 82, 119, 149, 152, 196f, 230, 257, 342).

The cellar master's keeper is first mentioned in 1335/36 (PUB 2, Nr. 879; PUB 3/1, Nr. 44). Apart from this, little is known from the sources about his activities. There is evidence that he accompanied the master or other territorial officials on trips (MTB, 151, 225, 554). In 1408, the master paid the medical expenses for the treatment of his cellar master. In 1406, the cellar master Michiel, who was not a brother, received a large sum when he left the court of the Grand Master (MTB, 386).

The cellar master had a boy as an assistant (MTB, 535). Since the sources of the order do not mention a cupbearer for the Grand Master, it can be assumed that this function was taken on by the cellar master's keeper. Therefore, the description of the duties of the chief cupbearer at the court of the Bishop of Warmia could also apply to the cellar master of Marienburg (SRW 1, p. 329f; FLEISCHER, p. 814). The latter had to prepare the host's table in the dining room before the meal, cover it with linen tablecloths, and decorate and clean the drinking cups for the bishop's table. Drinks were served only after the meal, and the chief cupbearer had to pay close attention to this. He poured the drinks into the goblets from a jug, the contents of which he first had to taste himself, and ordered the servants to carry them to the host's table.

For the cellar keeper, see JÓŹWIAK/TRUPINDA 2011, p. 242.

Cellar bollards (Kellerknecht)

Several knechts worked in the cellar of the Grand Master, whose job it was to supply the court with wine, beer and mead at the two daily main banquets and on other occasions. For this purpose, the drinks were poured from barrels into bottles and jugs and carried to the Great Remter. If the Master held meetings with territorial officials or guests in the palace, servants carried jugs and bottles along the system of servants' corridors. In addition, caring for drinking utensils (glasses, mugs, bottles, jugs) was one of the tasks of the cellar attendants. The account books list different types of cellar servants: cellar master's bollards (MTB, 87, 130, 191, 283, 554), wine cellar bollards (MTB, 459, 554; AMH, 289) and beer cellar bollards (MTB, 417, 447, 515; AMH, 257).

There is no reliable information about the exact number of servants in the basement. At the beginning of the 15th century, at least two knechts worked in the cellars at the same time.

Between 1400 and 1402, the cellar master's bollards Nikke (MTB, 87, 191) and David (MTB, 130) are mentioned. The wine and beer cellar bollards are usually only mentioned separately, but in 1409 there is a record of three cellar servants accompanying the Grand Master on a trip (MTB, 554).

The account books contain records of the payment of wages and clothing to the cellar clerks. Their room was located under the roof of the gatekeeper's chambers, which were very close to the cellar stairs in the forecourt (AMH, 181).

Horse Marshal (Pferdemarschall) and his Kumpan

The Grand Master had a large number of horses for himself and his court, which he kept in his own stables in the outer castle. The horses were looked after by numerous servants, headed by the Horse Marshal, who was an official of the Order. He could come from the circle of knights of the Order and subsequently make a good career. In 1401, the MTB notes that the former Horse Marshal now became the Vogt of Bebern in the Dobrin land (MTB, 90). According to this, this must have been Gottfried von Hatzfeld (HECKMANN 2014). His successor as Horse Marshal, Hans Stumer, on the other hand, was denied further promotion. He held this office from 1402 to 1410 (MTB, 179), and was then succeeded by a certain Paul (AMH, 21), under whom Stumer, however, continued for many years to supervise the grooms (AMH, 346).