Brewing in the Heiligenbeil district

In the second volume of the Complete Geography by the German geographer and historian Johann Hübner (1668-1731), which describes Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Prussia, Poland, Russia, Hungary, Turkey, Asia, Africa, America and “other unknown countries” (Vollständige Geographie, Von Dänemarck, Norwegen, Schweden, Preußen, Polen, Rußland, Ungarn, Turkey, Asia, Africa, America, und von den unbekannten Ländern), published in Hamburg in 1736, in the section “Brandenburg Prussia” in the chapter “Natangia” there is a short note dedicated to the “ancient city” of Heiligenbeil, ending with the phrase: “[The city] has good bread and good beer” (Es It seems that if even in Hamburg they knew about the “good beer” from Heiligenbeil, then the drink was really not bad.

We have already noted that the first beer in the territory of East Prussia was brewed in the castles of the German Order. With the appearance of cities on the lands conquered by the knights from the Prussians, monastic beer and beer brewed by the burghers of these same cities founded by the Order also began to appear.

Thus, historically, the first beer brewed in the Heiligenbeil district (the Kreis Heiligenbeil itself emerged as an administrative unit only in 1819) was beer from Balga Castle. It was this castle, founded by the knights on the site of the Prussian fortified settlement of Honeda in 1239, that later became a stronghold for the conquest of Sambia, Warmia and Natangia. The castle brewery was apparently located on the first floor of a narrow two-story outbuilding, located on the side of the Frisches Bay (now the Kaliningrad or Vistula Lagoon). It was the commanders of Balga Castle, which from 1250 was not only their residence but also the meeting place of the convent, who issued city rights to the settlements of German colonists arriving on Prussian lands. This was also the case in 1301, when the village of Heiligenstadt (the city was only called Heiligenbeil in 1344), which had been founded in 1272, received Kulm city rights.

In 1313, the village of Zinten (now Kornevo) also became a city. Since beer in the Middle Ages was, without exaggeration, “the first, the second, and the compote” for the population, any city dweller and free peasant could brew the so-called “table beer” (Tafelbier) — a light beer that contained virtually no alcohol — for their own needs in the required quantities without special permission. However, selling such beer was prohibited. The right to brew beer, and not only table beer, but even quite intoxicating beer, and then to sell it, was granted, in turn, to city dwellers, as well as aristocrats — owners of estates and large land plots. The latter, however, often farmed out the right to brew beer to innkeepers, or built inns and leased them out along with the right to brew and sell beer. The Teutonic Order also had its own inns. The Order's taverns were also managed by tenants, who were obliged to pay the owner a certain fee (the so-called chinsh) in money or in the form of produced goods.

The beer shortage could sometimes lead to very unexpected consequences: for example, during the War of the Horsemen (the war of the Teutonic Order with Poland in 1519-1521), the Balga garrison, consisting of mercenaries, almost rebelled because there were delays in issuing the required amount of beer. The garrison commander notified the Grand Master of the Order himself of the soldiers' discontent on August 17, 1520.

But usually there was still enough beer. Moreover, administrative measures were often used to sell beer brewed in breweries owned by an order or an aristocrat - innkeepers were simply obliged to buy beer from these breweries. And it was good if it was of decent quality.

The inn in the village next to Balga Castle has been known since 1447. During the heyday of the order, the inn also flourished. In 1536, after several decades of decline, the first Protestant bishop of Samland, Georg von Polentz, granted the inn to a district court official, Georg Thilo, along with the right to distill. In order to avoid competition, the village was forbidden to open a second inn. The inn owner was also granted the right to freely catch fish for his own needs in Frisches Bay using 15 fishponds. In addition to the castle beer, the inn also had the right to sell 12 barrels of beer purchased from outside every year, paying a tax of 2 sheets* for each barrel.

In the coastal village of Kalholz (no longer in existence), north-northeast of Balga, an inn has been known since 1523. The innkeeper was also given the right to free fishing in the bay using cages and nets, to harvest firewood and timber, and was also given the use of a meadow for haymaking. The annual tax was 9 marks. Apparently, over time, fishermen wishing to have a pint of beer could no longer fit in this inn, since in 1536 a certain Lorenz Simon received the right to open a second inn in Kalholz. Like the first innkeeper, he was obliged to sell 3 barrels of state beer, as well as fulfill the duties of delivering official mail.

Since 1431, there had been an inn in the village of Volitta, east of Balga. It was allowed to sell beer and food. For a chinsch of 5 marks, the innkeeper had the right to fish, keep 8 heads of cattle, and was given the use of a hayfield of 2 morgen**. However, no other inn could be opened on the road between Volitta and Balga. Fishermen from Frauenburg (now Frombork, Poland), who fished in these areas, were ordered to drink beer only in this inn or in the inn of Balga.

The Renzekrug Inn (by the way, the German word for tavern is " krug " and the German word for tavern keeper is "krug" , so the settlements ending in "-krug" most likely got their name from the tavern that once stood in their place, and the surname Kruger is quite common in German-speaking countries) near the Renzegut estate (which no longer exists) was rented out in 1387 for a chinsch of 4 marks and half a stein*** of wax "for the images of the Virgin Mary in the Balga castle" (candles were made from wax, which were supposed to burn constantly near the statues of the Virgin Mary in the castle church). There was supposed to be no other tavern between this tavern and the village of Fedderau (which no longer exists) in one direction, and no further than half a mile from Heiligenbeil in the other.

At the end of the 17th century, there were 24 state taverns in the Balga district (not counting the taverns owned by the nobility). Taverns were allowed to brew beer themselves, buy it from city brewers, but were still required to sell official beer from the castle breweries of Balga and Brandenburg (now Ushakovo). In addition to beer, they were allowed to sell wine and mead.

More or less profitable were taverns located on busy roads or in large villages. But even here the owners had to engage in agriculture or fishing in order to feed themselves. Taverns that could not cope with the sale of the obligatory volume of official beer or with the payment of chinsha could be punished with a fine, or even given to another tenant to manage.

In their own interests, innkeepers ensured that there was no illegal competition. In 1686, an innkeeper in Schönlinde (now Krasnolipie, Poland) complained about the local schulz (mayor) because he and several villagers were not drinking his beer, but rather the beer brought from Heiligenbeil, which was of better quality.

In 1712, a Bauer from Grunau (now Gronowo, Poland) was fined 12 marks for drinking a barrel of Heiligenbeil beer with his workers. For a similar offense, the fishermen's assistants from Alt-Passarge (now Stara Pasłęka, Poland) were fined as much as 100 marks - they preferred Heiligenbeil beer to the official beer.

The sale of "outside" beer was permitted only if visitors first ordered the official beer, or if the tavern was visited by noble persons.

In addition to the competition between beer brewed in state breweries and guild beer brewed in cities, there was a fierce struggle for the market between the cities themselves. In the 16th century, the guild brewers from Heiligenbeil, of which there were more than 100 (let us recall that it is necessary to distinguish between guilds that were related to beer production: as a rule, there was a guild of brewers in a city, which included the city nobility, and who had the right to brew and sell beer, but at the same time its members themselves had nothing to do with production, since the beer was directly brewed by hired master brewers, who could also have their own guild), fought against the expansion of their colleagues from Braunsberg (now Braniewo, Poland), which had been under the Polish crown since 1461. The renewed city rights of Heiligenbeil from September 10, 1560 even mention the “suffocating competition of neighboring Braunsberg.”

The economic war between Heiligenbeil and Braunsberg continued throughout the 16th century. Often, farmers from the surrounding villages smuggled the grain they grew to buyers from Braunsberg, which created a shortage in Prussia, which led to a shortage of raw materials for local brewers. The Heiligenbeil guildmasters complained that many innkeepers preferred to buy beer from Braunsberg rather than from them. In 1590, brewers complained that even artisans who did not have the right to do so were brewing beer in the city. As a result, in 1597, new city rights, confirmed in 1614, gave the right to brew beer to almost all residents of Heiligenbeil.

Despite all this, Heiligenbeil beer was still of excellent quality and deservedly in demand. Even during the Order's times, the cellarers of several surrounding castles bought guild beer from Heiligenbeil for the needs of the brethren. On December 21, 1407, two barrels of "Heyligenbylisch byers" were purchased for 11 marks and sent to Kovno (Kaunas) for 8 shillings. At the beginning of March 1438, three barrels of Danzig and Heiligenbeil beer, as well as two barrels of Königsberg beer, were stored in the cellars of Königsberg Castle. In 1440, the castle reserves consisted of four barrels of beer from Heiligenbeil and six barrels of beer from Königsberg.

There is a legend that the Grand Master of the Teutons, Konrad von Erlichshausen (1441-1449), sent two knight brothers around the lands of the Order, ordering them to try beer in different places and then report back to him where what beer was brewed. The envoys traveled to different cities, large and small, in Prussia, trying the intoxicating drink, and in order not to get confused, they gave the beer different names. For example, Königsberg beer was called Saure Maidt - "Sour Maiden". Braunsberg beer was called Stürzen Kerlen - "Falling Giants". Heiligenbeil beer received the nickname Gesalzen Merten - "Salty Merten". Perhaps because the brothers tried it on St. Martin's Day (November 11), or perhaps because the local beer was brewed from a brackish spring of water, and Martin-Merten was added for effect.

In 1690, Heiligenbeil brewers produced 624 brews, bringing in a good income for the town. Around 1710, there were about 150 houses in Heiligenbeil that had the right to brew beer, of which a third used this right every six weeks. "Gesalzen Merten" was drunk not only by the townspeople and residents of the surrounding area. The beer was sent to Danzig, West Prussia, Pomerania, and was escorted to Poland.

A little over a century later, in 1819, when Heiligenbeil received the status of a district center, the situation with brewing began to change. Although some burghers, despite the generally low prices for beer, continued to brew it, they were no longer a closed group enjoying this privilege. By that time, several years had already passed since the guild restrictions on production had been abolished and a law was in effect, according to which anyone could engage in any kind of entrepreneurial activity after paying a certain tax. A period of gradual decline of guild beer began. It was replaced by factory beer.

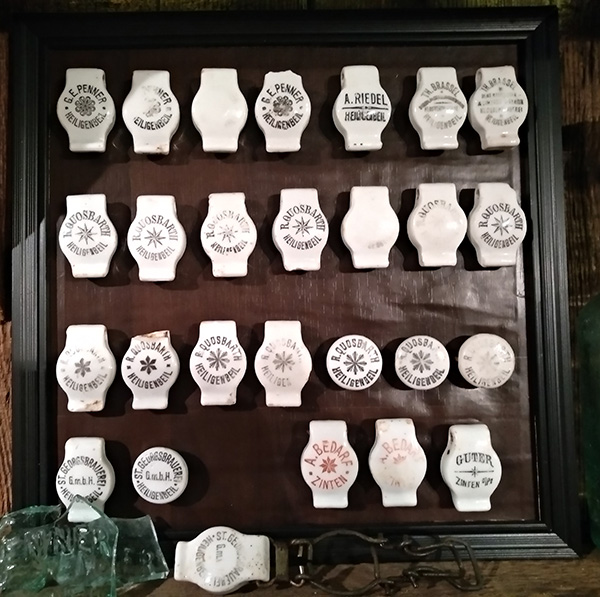

At the beginning of the second half of the 19th century, there were two breweries in the city. The first, Klosterbrauerei (Monastery Brewery), was founded in 1865 by the Mennonite Eduard Penner, who came from Marienwerder, and got its name from the Augustinian monastery that was located in Heiligenbeil from 1372 to 1520 near the eastern city gate. Beer from this brewery was served in the restaurant of the Haus Wiens hotel. The second brewery was built by Wilhelm von Saucken, a brewer from the village of Klinsch (Danzig district). It was located on Baderstrasse and was called St. Georgsbrauerei (St. George's Brewery). In 1867, the St. George's Brewery passed into the hands of Rudolf Kuosbarth.

But the relatively small breweries of Heiligenbeil and Zinten could not compete with the large Königsberg breweries of Ponart and Schönbusch, which belonged to the Schifferdecker family and mass-produced good beer at a relatively low price. For some time they passed from one hand to another, until they gradually went bankrupt.

In the 1930s, Zinten was home to a branch (possibly only a distribution one) of the Schönbusch brewery.

___________________

Notes:

* Scot ( or cattle) is a monetary unit equal to 1/24 mark

** Morgen is a unit of area equal to approximately 0.56 hectares.

*** Stein is a unit of mass equal to approximately 15.2 kg.

Sources:

Emil Johannes Guttzeit Balga (history of the village of Balga on the website balga.de)

ahnen-forscher.com/kirchspiel-balga

Carsten Fecker The beer in the Heiligenbeil region . — Newspaper of the Heiligenbeil wars, #46, 2001.