Brewing in East Prussia

One of the most important arts for us, as we know, is cinema. But for hundreds of millions of citizens of the Earth (as well as for the authors of this site), the art of brewing is no less important. Beer has been known since ancient times, because in Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt they brewed a drink based on fermented millet, and now it ranks third in the world in popularity, second only to water and tea. But with all due respect to the pyramids, we are still closer to a more recent history, and they are located far from our hearth. We decided to make a series of notes about brewing in East Prussia, whose roots go back to the times of the German Order and number almost eight centuries. During this time, many interesting things have happened, which will be useful to know not only for beer lovers, but also for history.

Brewing in East Prussia (or rather, its history) can be divided into three stages:

1. From the arrival of the German Order in Prussia until the first quarter of the 19th century. Beer was brewed according to guild traditions.

2. Late first quarter of the 19th century – late third quarter of the 19th century. The emergence of large breweries using modern steam equipment, the gradual displacement of small-scale production from the market.

3. 1870s - 1945. The era of industrial beer production.

One way or another, we will also have to talk about what happened after East Prussia was divided between the USSR and Poland, and there is no escaping the current state of brewing in the Kaliningrad region and northern Poland.

So, the first part of the cycle:

Brewing in the Middle Ages

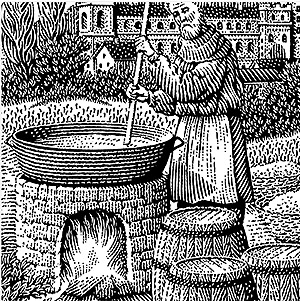

Having come from North Africa through the Iberian Peninsula to Northern and

Central Europe before the beginning of our era, beer began to spread to the

places of settlement of Germanic and Celtic tribes. Even a beer lover with the

most vivid imagination would hardly have been able to find the taste of today's

beer in that drink, created by soaking pieces of unbaked barley or rye bread

seasoned with various herbs in water. The first brewers were women who brewed

this intoxicating drink (once despised by the enlightened Romans) in bronze

cauldrons over fires for members of their tribe. There was simply no established

tradition or recipe, and the taste of the drink often depended on chance. Over

time, beer began to be brewed by members of individual families. But beer was

still not a commodity for sale or exchange, since brewed beer was stored for a

very short time, and was brewed only to satisfy their own immediate needs. The

monastic brethren were not averse to producing the foamy drink, since the drink

was often used instead of water, and being quite high in calories, it made it

easier to endure the hardships of numerous fasts.  It

was in the monasteries, which in the early Middle Ages were not only centers of

science and education, but also self-sufficient structures, almost completely

independent of the world around them, that the process of converting a mixture

of water and malt into beer turned into a science. Monks spent centuries honing

their skills in brewing and perfecting this process. In addition, it was in the

monasteries that beer was brewed in significant quantities for that time,

exceeding the needs of the monastery itself. Beer was given to the poor, who

shared meals with the monastery inhabitants, pilgrims and just travelers, and

its surplus was eventually sold, replenishing the monastery treasury. It is

believed that the oldest monastery brewery in the world, preserved to this day,

is located in the Benedictine Abbey of St. Gallen in Switzerland. It is also

interesting to look at the plan of the ideal monastery (the so-called "St. Gall

plan"), created around 830. It shows, among many different buildings, three

breweries at once: for noble guests, for monks and for pilgrims and beggars. In

addition, the plan includes a room for grinding malt and grain, as well as a

cellar for storing finished products with an approximate volume of 350

hectoliters.

It

was in the monasteries, which in the early Middle Ages were not only centers of

science and education, but also self-sufficient structures, almost completely

independent of the world around them, that the process of converting a mixture

of water and malt into beer turned into a science. Monks spent centuries honing

their skills in brewing and perfecting this process. In addition, it was in the

monasteries that beer was brewed in significant quantities for that time,

exceeding the needs of the monastery itself. Beer was given to the poor, who

shared meals with the monastery inhabitants, pilgrims and just travelers, and

its surplus was eventually sold, replenishing the monastery treasury. It is

believed that the oldest monastery brewery in the world, preserved to this day,

is located in the Benedictine Abbey of St. Gallen in Switzerland. It is also

interesting to look at the plan of the ideal monastery (the so-called "St. Gall

plan"), created around 830. It shows, among many different buildings, three

breweries at once: for noble guests, for monks and for pilgrims and beggars. In

addition, the plan includes a room for grinding malt and grain, as well as a

cellar for storing finished products with an approximate volume of 350

hectoliters.

The Christianization of Germanic tribes in Western and Central Europe, which continued for three centuries after the fall of the Roman Empire, the disintegration of the tribal system and the emergence of states based on a common language and customs, entailed a struggle for power between the emerging secular feudal lords and Christian bishops, who relied in their struggle on the monasteries that had already emerged by that time. This struggle, among other things, included control over beer production.

Charlemagne, King of the Franks and later Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, in his Capitulare caroli magni de villis, a manual for managing his estates published around 795, required, among other things, “that every manager have good masters in his charge, namely <…> brewers, that is, those who are knowledgeable in the production of beer, apple, pear and other various drinks.”

Before hops were used to brew beer (and the first hop plantations in what is now Bavaria appeared as early as the 730s), a mixture of herbs called gruit (gruit is Old German for "wild herbs") was added to the drink to give it flavor. Everyone was allowed to brew beer, but not everyone could collect gruit, or more precisely, sell it as a mixture used in brewing beer. The right to distribute gruit was monopolized by the crown, which shared this right with the church (which, in turn, gave permission to individual monasteries to use gruit). Brewing beer without adding gruit was prohibited. Later, gruit came to be called not only beer brewed with the addition of this mixture, but also the tax paid for the right to brew the drink. To avoid tax evasion, the composition of the mixture was kept secret.

Hops gradually began to replace gruit at the beginning of the 9th century. The first to appreciate its beneficial properties were the same monastery brewers. In general, the main merit in the fact that beer brewed in the monastery became synonymous with quality belongs to hops, which gave the drink, which had previously had a very sweet taste, a specific bitterness, the same taste of beer that everyone knows now! In addition, hops served as a natural preservative, increasing the shelf life of beer and, in addition, allowing it to be transported over longer distances. All this made it possible to brew beer of approximately the same taste, inherent in different batches of beer.

The use of hops in brewing was akin to a small revolution in this business. Hops would later replace gruit and become a very popular product, with which taxes were even paid. But there was no monopoly on growing hops. And although in some countries (for example, in England and the Netherlands) hops were banned for a long time), over time it was hops and European monks who turned beer into the drink we drink to this day.

By

the 11th century, the right to brew (and sell!) beer in the Holy Roman Empire

was almost exclusively reserved for monks (Benedictines and Franciscans). This

was the heyday of monastic beer. Some monasteries sold 2,500 barrels of beer

annually. In the Holy Roman Empire, a country with a population of 9-10 million

people, there were about 500 monastic breweries, 300 of which were in Bavaria.

Some monasteries treated local residents to their “church ale” for free on major

holidays.

By

the 11th century, the right to brew (and sell!) beer in the Holy Roman Empire

was almost exclusively reserved for monks (Benedictines and Franciscans). This

was the heyday of monastic beer. Some monasteries sold 2,500 barrels of beer

annually. In the Holy Roman Empire, a country with a population of 9-10 million

people, there were about 500 monastic breweries, 300 of which were in Bavaria.

Some monasteries treated local residents to their “church ale” for free on major

holidays.

The growth of production and sale of monastic beer eventually led to its collapse. Not only did a wave of indignation begin to rise among the clergy over the monks' mired in drunkenness (in some monasteries each monk drank up to five liters of beer per day) and greed, but in the 12th century the rulers and feudal lords themselves realized that it was foolish to miss the opportunity to replenish their ever-thin treasury with income from beer sales, and began to deprive the monasteries of their monopoly on the production and sale of beer, organizing their own breweries (Hofbräuhaus) at their courts. It should be noted here that the loss of the monopoly on brewing, as well as the warming of the climate that began in the first few centuries of the second millennium AD, led to the monasteries becoming involved in winemaking, achieving outstanding success in this area as well.

The loss of the beer privilege by the monasteries coincided with the beginning of the growth of cities in Europe and the emergence of the burgher class. The separation of artisans and merchants from rural residents turned them into a third force (eventually defeating their rivals who had missed their appearance) in the struggle for the right to brew beer, and then to sell it. By this time, beer (and the raw materials for its production) had become a full-fledged and very profitable commodity. The growth in popularity of beer was also facilitated by the emergence of numerous taverns and inns along European trade routes. Thus, the more good full-bodied beer appeared on the market, the greater the demand for it became, the more beer was brewed not in monasteries, but in city breweries.

So, in the 12th-13th centuries, the process of forming craft guilds in Europe was more or less completed. At the same time, beer was already being brewed in Germany using hops (it should be noted that until the beginning of the 16th century, all beer brewed in Europe was a variety of ale, and lager appeared only five centuries ago; moreover, beer in the Old German dialect was called öl, surviving to this day in the name of top-fermented beer - ale). Well, and in 1232, the knights of the German Order, having received the Chełmno (Kulm) land from Konrad of Masovia, founded their first fortification on the right bank of the Vistula - Thorn. The second stronghold of the knights on the lands of the Prussians - Kulm (Chelmno), which quickly turned into a city - gave the name to one of the varieties of medieval city law - Kulm. Over the next half century, the knights took control of almost the entire territory inhabited by the Prussian tribes, building castles on the conquered lands, which became a kind of center of attraction for German colonists who settled under their protection together with the Prussians loyal to the order. Over time, settlements began to form around the castles (and not only around them), some of which subsequently received city rights from the Master of the Teutons, which, among other things, implied the right to brew and sell beer at fairs, as well as in the surrounding villages and hamlets. Until then, beer in those lands that fell under the rule of the order was brewed in knightly castles and a few monasteries. Castle breweries provided "liquid bread" not only for the knights and their knechts, but also for numerous castle servants engaged in various jobs.

Over time, professional brewers also appeared among the German colonists, and beer from castle and monastery breweries became not the only one available to residents. Breweries that emerged outside of castles and monasteries began to bring income to the treasury of newly formed cities.

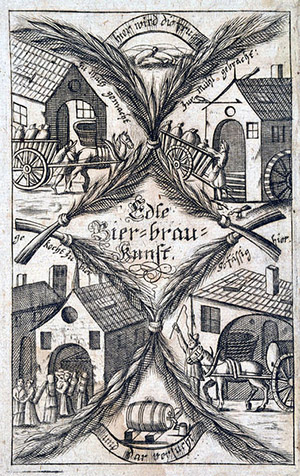

Production technology

So, what was the process of brewing beer like in the Middle Ages?

This is how Simon Sirenius described it: windmills and even those using animals as energy to rotate the millstones (one of these mills was in Marienburg Castle). In small towns and villages, the same mills that ground grain into flour were used to grind malt. These mills usually had a special millstone for grinding malt. They tried to use the ground malt immediately, although it could be stored as flour for up to a year. Malt was an item of wholesale trade. From the mid-16th to the mid-17th century, approximately 2,000 lasts were transported by ship across the Oresund Strait every year .

To the mills where it was ground. A separate malt mill was also the property of the city, and met the needs of both breweries and distillers, and sold part of its products to consumers from neighboring villages and other places. During the 17th century, the mill processed 1000-1500 pieces of malt annually (1 piece - a measure of bulk solids - consisted of 60-75 korets, 1 korets - about 55 liters). For grinding a piece of malt in the middle of the 17th century, the mill received 2 hryvnia. The miller paid the apprentices for their work. At the end of the 17th century, the miller himself received a house with a vegetable garden, firewood, as well as payment for the actual grinding of the malt from the city authorities free of charge. At the same time, the miller had to maintain the mill in good technical condition at his own expense (except for the millstones).

The Elbing magistrate, in addition to the production and milling of malt, also tried to control the delivery of raw materials (barley) purchased by brewers to the malthouses, as well as malt to the mill. Naturally, the city authorities charged for transport services. For example, in 1675, a fee of 50 groschen was charged for the delivery of a piece of malt to the mill.

Thus, it turned out that brewers only brewed beer in their own breweries. But the practice often deviated from the guild charter (one brewer - one brewery), and some guild members brewed beer on other people's equipment. In 1631, out of about 130 Elbing brewers, only a quarter brewed beer with the maximum permitted frequency (once a month). A third of them brewed beer only once a quarter. The majority did it twice a quarter. Therefore, maintaining their own brewery was beyond the means of some of the brewers. This led to some guild members temporarily renting breweries from their fellow guild members. Thus, the owners of the breweries were not always the beer producers, and the producers were not always the owners of the breweries. The most important and most expensive equipment at that time were copper kettles for brewing beer. And they were often owned by more than one owner. The kettles could be the common property of the guild and were installed in the premises of a specific guild member during the brewing period. The tenant of the kettles paid a fee for each brew (Pfannengeldt) to the guild's cash desk. At the beginning of the 17th century, the brewers' guild of the Old Town of Elbing owned three kettles, by the middle of the century - already 6, and in the 1690s - 7 kettles.

In the absence of his own kettles for brewing beer and the impossibility of renting them for a certain period, the brewer was allowed to brew weak beer in small kettles belonging to the guild or its members.

It should be noted that the owners of the equipment themselves, as well as its renters, did not take part in brewing beer. The malt, hops and firewood for the boilers prepared in the malthouses and at the mill fell into the hands of professionals who, for a certain fee, brewed the beer.

By 1481, there was already a guild of hired brewers, the "Schupfenbrauer", in Elbing. They supervised the work of apprentices and various assistants (water and beer carriers, barrel cleaners, etc.) during the brewing of beer, receiving payment for each brew, as well as food during the work. In the second half of the 16th century, as in the 17th century, the "Schupfenbrauer" guild had 20-30 members, working for both the brewers' guild of the Old Town and the guild of the New Town.

Thus, to sum up, it can be stated that in the process of brewing beer, from the process of purchasing raw materials to obtaining the finished product, the following took part:

- Meltzenbrauer brewers are the owners or lessees of the brewing kettles, the holders of capital and raw materials;

- Malt producers;

- Malt millers;

- Professional brewers from the "Schupfenbrauer" workshop;

- Various apprentices and unskilled workers.

All groups of participants, except the first, were, in fact, hired personnel. It should be noted that the city authorities played a rather important role in this process.

The breweries' competitors were rich noble families who organized their own breweries in their suburban estates, as well as village breweries and taverns, which often brewed beer illegally. Some village priests did not disdain to brew beer underground. The Elbing Hospital of the Holy Spirit was a legal competitor. Part of the drink brewed in its brewery was consumed in the hospital itself, the remainder was sold.

A few words about the situation in Danzig. Among the members of the brewers' guild there, many also did not have their own breweries or even brewing equipment. In the second half of the 16th century, the guild had about 150 members, but by the middle of the 17th century their number had fallen to 54.

The members of the guild bought the raw materials in bulk. The malt was produced not in the city or guild malthouses, but in the breweries themselves. The prepared malt was transported to a mill, which was the property of the city. After that, the malt was returned to the brewery, where the beer was brewed. Thus, the city participated in the beer production process to a much lesser extent than it did in Elbing.

In the brewery itself, the guild brewer (Meltzenbrauer) did not take direct part in brewing beer. The malt was prepared by professional maltsters, and the brewing itself was supervised by professionals from the guild "Schoppenbrewer", who were paid for each brew. They were assisted by senior apprentices "Meisterknecht", who after four years of work could already become brewers themselves. The brewery also had unskilled workers (including women): carters, porters, woodcutters, etc. That is, in general terms, the brewing process was similar to how it took place in Elbing. At the same time, there were some differences in the sale of beer. The monopoly of the Danzig guild of brewers on the production and sale of beer existed, in fact, only on paper. The main competitors for legal brewers were breweries opened in the estates located around Danzig. And despite numerous promises from the city council to close them, the promises remained just words, since many city councilors were the owners of these breweries.

The

situation was similar in Thorn. As early as 1400, there was a brewers' guild

("Brauherren"). In the 16th century, the guild received a monopoly on the

production and sale of beer in the city and its environs. In the middle of the

16th century, the guild numbered about 80 people, in 1598 - 58 people, in 1648 -

36, in 1680 - 22 people. As in Danzig, the Thorn brewers formally belonged to

the merchants of the third guild (like bakers and butchers), but in fact they

occupied a place between merchants and artisans. Members of the guild were both

representatives of noble families and city councilors. A condition for joining

the guild, as in Elbing, was the presence of a brewery. As a rule, the brewers

were also the owners of malthouses, which were part of the brewery. In Thorn in

the mid-16th century there were two malt mills (in the Old and New Town). Guild

members were obliged to grind their malt there, paying a certain fee to the

city. As in Elbing and Danzig, the breweries employed hired maltsters and master

brewers, who were paid for their work on a per-piece basis and per-brew basis,

respectively. The main problem for the brewers' guild was the beer brewed by the

city in its own breweries, the first of which opened in 1608 near the city. The

magistrate subsequently founded three more breweries in the vicinity of Thorn.

Freed from the need to pay for the milling of malt, these breweries had a

competitive advantage over the breweries of the guild members. Gradually, the

drinks produced in the city breweries crowded out competitors in the city's

outskirts, and then began to crowd out the products of the guild members in

Thorn itself, which caused a significant reduction in the number of "Brauherren"

members.

The

situation was similar in Thorn. As early as 1400, there was a brewers' guild

("Brauherren"). In the 16th century, the guild received a monopoly on the

production and sale of beer in the city and its environs. In the middle of the

16th century, the guild numbered about 80 people, in 1598 - 58 people, in 1648 -

36, in 1680 - 22 people. As in Danzig, the Thorn brewers formally belonged to

the merchants of the third guild (like bakers and butchers), but in fact they

occupied a place between merchants and artisans. Members of the guild were both

representatives of noble families and city councilors. A condition for joining

the guild, as in Elbing, was the presence of a brewery. As a rule, the brewers

were also the owners of malthouses, which were part of the brewery. In Thorn in

the mid-16th century there were two malt mills (in the Old and New Town). Guild

members were obliged to grind their malt there, paying a certain fee to the

city. As in Elbing and Danzig, the breweries employed hired maltsters and master

brewers, who were paid for their work on a per-piece basis and per-brew basis,

respectively. The main problem for the brewers' guild was the beer brewed by the

city in its own breweries, the first of which opened in 1608 near the city. The

magistrate subsequently founded three more breweries in the vicinity of Thorn.

Freed from the need to pay for the milling of malt, these breweries had a

competitive advantage over the breweries of the guild members. Gradually, the

drinks produced in the city breweries crowded out competitors in the city's

outskirts, and then began to crowd out the products of the guild members in

Thorn itself, which caused a significant reduction in the number of "Brauherren"

members.

To sum up, it can be said that a similar situation in the organization of the brewing process was in all the major cities of Prussia: hired workers worked in the breweries owned by the members of the guild, and everywhere the products of these breweries experienced competition from producers located in the vicinity of the city, and the city authorities either turned a blind eye to this, or themselves participated in the organization of the breweries.

The situation was different in small towns with a population of several hundred to several thousand inhabitants, of which there were plenty in Prussia at that time.

Marienburg, with a population of 5,000, did not have its own brewery, and the right to brew beer was available to any resident of the city who owned at least half of a house. In 1586, approximately 170 residents of the Old and New Towns of Marienburg (including ten city councilors) enjoyed this right. The magistrate tried to regulate the volume of beer production in the city by limiting the frequency of brewing. For example, in 1577, owners of a whole house were allowed to brew beer once every three weeks, and owners of half a house - once every six weeks. In the second half of the 17th century, owners of houses were allowed to brew beer once every four weeks.

The burghers owned both malthouses and breweries. The malthouses employed hired workers who were paid for each piece of malt produced. It is clear that all expenses for malt production, including the purchase of raw materials and firewood for drying, fell on the shoulders of specific organizers of beer production. The dried malt was taken to the mill of the castle of Marienburg. The mill did not belong to the city, but was managed by the castle steward, and served the interests of not only the residents of Marienburg, but also the peasants from the outskirts of the city. The fee for milling malt (Maltgielt) was divided into two parts: more than two thirds went to the castle's income, the rest went to the miller for his work. The ground malt was taken by the townsman to his brewery. It is hard to imagine that all 150-200 people brewing beer in the city could afford to buy their own brewing kettles, especially since about every tenth of them brewed beer only 2-3 times a year at the end of the 16th century. And only about a third of brewers used their right to the maximum, brewing beer 15-16 times a year. Most likely, as happened in large cities, beer producers united into some groups, sharing the costs of purchasing equipment, or rented it from owners.

There is information that in 1670 there was a city brewery in Marienburg, the services, or rather, the equipment of which could be used by citizens who did not have their own. At the same time, the city also controlled the volumes of production of the foamy drink.

For brewing beer, at least since the second half of the 16th century, the burghers, like everywhere else, hired professional brewers. They came with their own apprentices. The master brewer was forbidden to brew beer for two customers at the same time, which apparently often happened in practice. Woodcutters and water carriers (Wasserzieher) worked side by side with the brewer. They all received payment for each brew. In 1578, the master brewer received 11 groschen, the water carrier - 9 groschen, the woodcutter - 7 groschen. In addition, each worker had a certain amount of weak beer per day for free.

As we can see, there were significant differences in the organization of the brewing process in Marienburg, and first of all, there was no brewers' workshop, as well as the associated monopoly (albeit often formal) on beer production. The beer itself, as everywhere, was brewed in the city by hired workers, and the organizers of production only purchased raw materials, firewood and, in some cases, equipment (or rented it). At the same time, there was no problem of illegal beer production in Marienburg. Local beer was sold in the city and several dozen taverns located on lands belonging to the castle. Beer brewed in the castle itself, until the middle of the 16th century, met the needs of the castle servants and workers of the castle manor. Then, at the turn of the 17th and 18th centuries, castle beer began to be brewed for sale.

In Graudenz (Grudziądz) with a population of 2,000 people (in the 16th century), any townsman who owned at least half a house had the right to brew beer. As a rule, each house was initially built with the expectation that beer would be brewed in it (it is noteworthy that in Polish the basement of a house is called "pivnica"). At the same time, the city authorities exercised control over production. From about the 1590s, all townspeople were obliged to use the services of the city malthouses, and possibly also the city breweries, for brewing beer. For example, in 1608, the city had three malthouses (Malzhaus) and two breweries (Brauhaus). Although some townspeople still had their own breweries. At the same time, the city charged for the use of the water supply. For each brew, the producer paid a water tax (Wassergeld) to the city treasury. The city thus assumed the costs of providing residents with water, and at the same time received additional deductions to the treasury, and also controlled the volumes of beer production. In this situation, those wishing to brew beer only had to worry about purchasing raw materials (barley and hops) and firewood, as well as pay for the work of professional maltsters (Mälzer), brewers (Braumeister) and their apprentices (Brauhelfer). The master and his apprentices were responsible for the entire process of brewing beer, from transporting the malt to the mill to filling the barrels with the finished product, while bearing responsibility for the raw materials entrusted to him, including imprisonment.

In the other small towns of West and East Prussia, the organization of brewing was no different from that in Marienburg or Graudenz. In some places, only homeowners were granted the right to brew beer, in others, all townspeople. Only the permitted frequency of brewing varied from town to town.

As an example, we can consider the situation in Fischhausen (now Primorsk). The settlement received a charter for the foundation of the city under the Kulm law in 1305 from the Bishop of Samland, Siegfried von Reinstein. The population of the city in 1768 was 876 people, in 1798 - 992, and in 1810 - 1017 people. In 1810, the city had only 134 residential buildings, 9 houses were used for public purposes, and 4 more houses were used by artisans for their own needs. As we can see, Fischhausen was, even for those times, a small town. However, it was precisely such tiny towns that made up the majority of urban settlements not only in Prussia, but also in Western Europe.

Fischhausen received the right to brew and sell beer rather late, in the 17th century, during the reign of the Brandenburg Electors . As of 1694, there were 30 burghers in the town who had the right to brew and sell beer, and three burghers who had the right to sell beer at retail. All of them were owners of houses in the town. Some of them owned two or three houses at once with the right to brew beer in them. Each burgher (or rather, each house owner) brewed beer in turn. The brewed beer was sold for 4 weeks, then the right to brew beer passed to the next in turn. It is noteworthy that among those 30 residents of Fischhausen who owned houses and the right to brew beer in them, a significant number were members of the city council and government officials, as well as their widows. Here is a list of the positions of some of the Fischhausen brewers: deacon, member of the magistrate, city treasurer, chief amber assessor, clerk of the amta, judge, assistant judge, burgomaster, assessor, retired former consul, tax collector. Among the brewers there were also several craftsmen and their widows (hairdresser, potter, saddler, tailor).

The two brewing kettles were the common property of the brewers. When not in use, the kettles stood on the market square in front of the town hall. The beer brewed in Fischhausen could only be sold in the town. In the surrounding villages, there were taverns and inns that sold beer brewed in the breweries located on the domain lands (i.e. owned by the crown) - in the Amt settlement and Lochstedt. The brewery of the Amt settlement, located on the outskirts of Fischhausen, already existed during the time of Duke Albrecht. Since then, there have also been several inns in the settlement, the oldest of which received the right to retail beer from the Duke on March 5, 1567.