Amber Regalia

In general terms, the amber regalia (amber regal, amber privilege) is a monopoly on the extraction and sale of amber. The first written evidence of the amber regalia dates back to 1312, when Karl von Trier was the Grand Master of the German Order. At that time, the responsibility for collecting and catching amber was assigned to fishermen on the Samland coast, who also had to deliver the collected amber to certain collection points. However, the amber regalia probably appeared much earlier, with the emergence of the Samland bishopric on the Prussian lands. In 1342, the right to control the collection of amber passed to the monastery in Oliva. The payment for the collected and delivered amber was money and salt. However, the amber regalia was finally formed by the end of the 14th century. At times, the German Order leased out the amber regalia on certain sections of the coast. There were several versions of the amber regalia. According to the law of 1394, the collection and storage of unprocessed amber was prohibited. Violators were threatened with a fine, and no later than the end of the 15th century, the punishment could be the death penalty. In order to prevent the smuggling of amber products, a ban was even introduced on the profession of amber carver in all lands of the order, and all collected amber was sold by the order either as raw material or sent for processing to its affiliated masters in Lübeck, Bruges and Venice.

The Order appointed special "amber lords" (Bernsteinherren) from among its brethren. They had a coast guard under their command, who monitored the compliance of the coastal inhabitants with the amber law. The residence of the Bernsteinmeister, the leader of the amber lords, was Lochstedt Castle until the end of the 16th century. Then the coast guard was located in the village of Germau (now Russkoe), and under the Great Elector Friedrich Wilhelm, from 1644, also in Memel (now Klaipeda).

Thus, no local resident had the right to sell or even store the amber collected or caught in the sea. It had to be handed over to the Order's amber collectors (naturally, at a very low price).

The amber regalia of the Order was shaken after the signing of the Second Peace of Torun (1466), according to which the Order lost a significant part of its lands (in particular, the Frische Nehrung spit (now the Baltic or Vistula spit), which provided about a third of all the collected amber), which went to the Free City of Danzig and Poland. Competition in the amber trade appeared. The Order began to trade not only in raw amber. In 1533, the last Grand Master of the Order, who became the first secular ruler of the Duchy of Prussia, Albrecht of Brandenburg-Ansbach, transferred the amber regalia "in perpetuity" to the merchants of the Jaski family from Danzig, but already in 1642 he revised the agreement. From then until 1811, the amber regalia remained in the hands of the state and was only leased to merchants.

In 1617, during the reign of Elector Johann Sigismund, the penalties for illegally collecting amber on the beach were tightened. In addition to the previous regulations, anyone who was not a local resident and did not have a special permit was prohibited from entering the beach (this ban remained in effect until 1885). Anyone who fished amber out of the sea or collected it on the beach was sent to the gallows that were built along the coast. Those suspected of theft or illegal collection were subjected to cruel torture.

The laws remained no less severe under the Great Elector Friedrich Wilhelm (1640-1688). In 1644, a law was passed that required all male coastal residents over 18 years of age to take the so-called "coastal oath" that they would not illegally collect amber and undertake to inform on anyone involved (by the way, according to the law of 1801, the informer was entitled to a reward of half the value of the confiscated amber). For example, for the theft of a pound of amber, a fine of 90 Prussian guilders or the corresponding prison sentence was imposed. For two pounds of stolen amber, the punishment was doubled. The penalty for three pounds was a fine of 270 guilders, flogging and a ban on living on the coast for 10 years; for four pounds, in addition to the fine and flogging, there was also the pillory, and then a lifelong ban on living in the country. For five pounds of amber, the punishment was the gallows and double payment for the stolen goods. For an especially large theft (25 pounds or more), the punishment could even be breaking on the wheel. Even just being on the coast without permission was punishable by a fine of 12-18 guilders, with exile from one to three years for a repeat offense.

But even gallows along the coast and numerous oaths taken by local residents could not completely eradicate amber smuggling. All able-bodied residents of the coast had to fish for amber, receiving payment comparable to what they could earn by fishing themselves. This state of affairs led to the fact that the theft of amber among local residents was not considered something shameful. If the sea itself throws amber onto the beach, they believed, thereby giving us the opportunity to take amber from the land and feed ourselves, then how is this theft?

Along the entire coast from Danzig to Memel, which was divided into special sections, three times a year (at Christmas, Shrove Tuesday and Midsummer) the coast guard appeared for inspection, who had the right to inspect any home and assess the growth of its owner’s wealth – whether this growth was caused by the sale of illegally collected amber.

Under Elector Friedrich III (1688-1713, King of Prussia from 1701), only minor changes were made to the law. However, in Palmnicken (now the village of Yantarny), where one of the coastal inspectors was located, a prison for amber smugglers was built in 1690.

Under the "soldier king" Friedrich Wilhelm I (1688-1740), the punishments for stealing amber were softened. Only those who stole more than a quarter of a ton and had already been convicted of theft were executed. In addition, peasants were now paid in money for the collected and handed in amber, not salt. Coast guard inspections began to be held every three years. But all men still had to take a "coastal oath", from which even priests were no longer exempted.

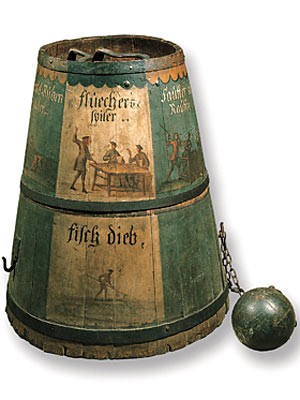

In 1762, under Frederick the Great, the punishments became even milder. Death or exile from the country were no longer practiced. But imprisonment (from 8 days to 4 weeks) on bread and water, plus a flogging of the "hello and farewell" type (i.e. at the beginning and end of the term) was in use. Foreigners detained on the shore, regardless of whether they were caught smuggling amber or not, faced either a "Spanish mantle" (a device in the form of a conical barrel without a bottom and with a hole for the head at the other end, put on the torso of the punished person), or a couple of days of imprisonment, all on the same bread and water.

The situation changed only in 1807, when the amber regalia was given to several merchants. Residents of the coast were freed from forced labor to collect and transport amber, as well as from inspecting their homes. And in 1811, local residents were also allowed to collect amber. In 1837, Friedrich Wilhelm III gave all amber mining in the Danzig region to the coastal communities for 10,000 thalers. The treasury's income from amber privileges decreased, but seaside resorts began to appear on the coast and people could freely come to the sea.

But the free collection and extraction of amber was still prohibited. For example, the law issued in 1924 by the Prussian Ministry of State, which regulated all forms of amber extraction and collection, implied fines and imprisonment for violators. Even amber accidentally found on the beach had to be handed over to a special collection point. Formally, the ban on the free collection of amber on the coast was lifted only in 1945. It should be noted that, for example, in Denmark there was also an initial ban on the free collection of amber, which was lifted, however, already in 1843. Before that, violators were subject to punishments up to and including imprisonment.

By the way, numerous "amber fishers" who appear during storms on the coast of the Kaliningrad region do not violate any laws, since they only "collect" what the sea throws up on the shore. Illegal amber mining is prohibited, and therefore there are always reports of police arresting "black diggers" or divers who dive into the sea and use pumps to wash away the bottom to mine amber. But, as you now know, even the death penalty did not discourage people from smuggling "northern gold".

Sources:

Wikipedia

Georg Hermanowski. Ostpreussen — Lexicon. Augsburg, 1996.

Kerstin Hinrichs. Bernstein, “Precious Gold” in Art and Natural History Museum and Museum of the 16th – 20th centuries. – Berlin, 2007.

Karl Engelhard. Der Bernstein. 1874.