7 Years War in East Prussia: the battle at Sceerandszene

Memorial stone

In the village of Vorotynovka in the Chernyakhovsk urban district of the Kaliningrad region there is a memorial stone dedicated to the events of the Seven Years' War in East Prussia. It is known that it lay covered with earth for many years on the outskirts of the village, and in 2008 it was restored on its own pedestal by searchers from the historical and local history society "White Raven" from Chernyakhovsk and local residents [1].

There are three inscriptions carved into this boulder.

On the front side of the stone is written: “Gefecht bei Szierandszen zwischen Russen und Preussen am 20ten August 1757 am siebenjahr Kriege” (“Battle of Szierandszen between the Russians and Prussians on August 20, 1757 in the Seven Years' War”) [2].

On the back of the stone, due to chips, only individual words are legible: “Wier Deutsche …(r)сhten Gott ….Niemand”. Apparently, the original text read: “Wier (=Wir) Deutsche fürchten Gott, sonst Miemand” (“We Germans fear God, (but) no one else”) and was a paraphrase of a quote from Chancellor Bismarck’s famous speech in the Reichstag on February 6, 1888: “Wir Deutschen fürchten Gott, aber sonst nichts in der Welt” (“We Germans fear God, but nothing else in the world”) [2].

On the side of the stone is written: "Gott segne Kaisers Reich" ("God bless the Kaiser's empire") [2].

In all likelihood, the inscription was originally only on the front side, the back and side inscriptions were added after 1888 to raise the patriotic spirit of the people of the newly born German Empire. They differ noticeably in their font and line spacing. It must be assumed that the memorial stone was erected even earlier.

Battle of Sceerandscene

What happened here on August 20, 1757 (here and below all dates are given according to the Gregorian calendar), ten days before the decisive battle between the Russians and Prussians at Gross-Jägersdorf?

There is no information about the Battle of Szirrandszen in the works of such authoritative researchers of the Seven Years' War as military historian Dmitry Fyodorovich Maslovsky [3] and French historian Alfred Rambaud [4]. There is no information either in the memoirs of Andrei Timofeevich Bolotov, a second lieutenant in the Apraksin army, who went with it through East Prussia from the beginning to the end of the campaign [5]. The only mention of Szirrandszen is found in the book by E.K. Thiel "Statistical and Topographical Description of the City of Tilsey" [6]. It contains the diary of the vice-burgomaster of the city of Tilsit (now Sovetsk) Andreas Rösenik, which he kept from July 27 to October 4, 1757, during the stay of Russian troops on the territory of East Prussia. In his diary, Rösenik reports:

“On August 21, many Tatars from Apraksin’s army broke through here [to Tilsey], some of them had sabres and rifled barrels, others were equipped [armed] with bows, each had a quiver with 30 arrows on his back. Along with this, they brought with them on a cart 8 wounded Prussian hussars, captured during the skirmish near Szirandzen [unlike the stone in the diary, it is written Szirandzen — Yu.B. ]. The Tatars drove a large number of sick and lame horses before them and [then] left across the pontoon bridge” [6, p. 42; 2, p. 24].

It follows from this message that Tatars from Apraksin's army and Prussian hussars participated in the battle near Scirandszen. This can only be confirmed indirectly by comparing other known testimonies of the military campaign of 1757.

According to Maslovsky, the Tatars (Kazan) from the "mixed-national team" [the irregular cavalry of Apraksin's army, which included baptized Kalmyks, Kazan Tatars, Meshcheryaks and Bashkirs. - Yu.B. ] numbering 500 horsemen (according to other estimates - up to 1.5 thousand [7]) were part of the irregular cavalry of Field Marshal S.F. Apraksin's army [3, pp. 50, 51, 68, 250]. The horsemen of the "team" were "two-horse", they had two horses each. The second horse was loaded with provisions, military equipment and was also a "horse reserve" in case of injury or loss of horses in battle. The "team" was not connected with the army convoys, it obtained its own food and forage. Therefore, it was extremely mobile and fast, but at the same time anarchic and difficult to control [7]. The "team" was armed with bows, pikes, sabres and guns. Rösenik also mentions them in his diary.

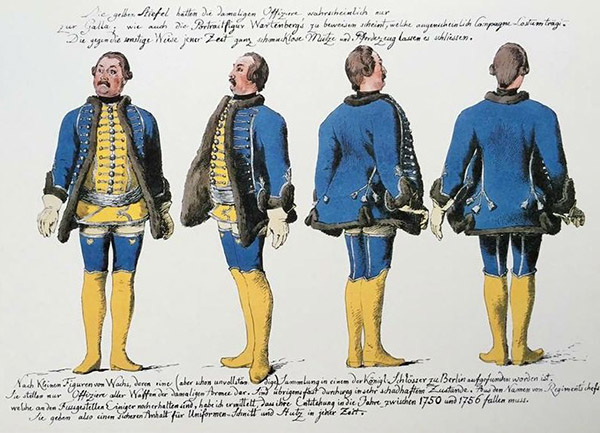

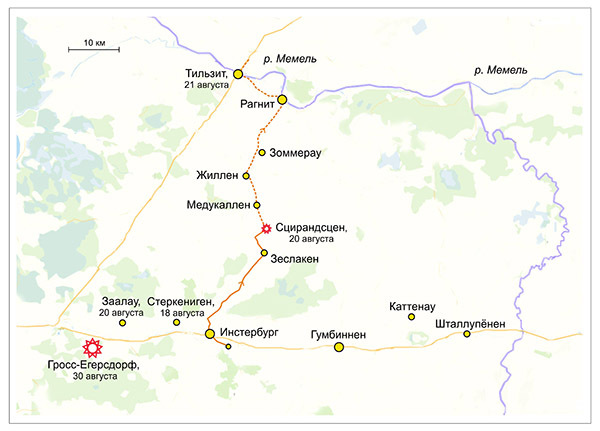

On August 1, 1757, the Russian army under the command of Apraksin entered the territory of East Prussia. On the same day, a skirmish took place between the vanguard of the Russian army and the hussars of the Prussian Colonel Malakhovsky [3; 5] at Kattenau [now Furmanovka] - Kummeln [now does not exist], where the Russians suffered significant losses. After the capture of Stalupyan [Stalluponen, now Nesterov] and Gumbinnen [now Gusev], there was fighting for Insterburg [now Chernyakhovsk], which changed hands several times, but was finally captured by the Russian army on August 11. On August 13, Apraksin himself arrived in Insterburg. On August 15, a military council was held here, at which it was decided to divide the irregular cavalry of Apraksin's army into two detachments and move them to the vanguard on both banks of the Pregel [now Pregolya] for reconnaissance. The right cavalry detachment, numbering 3 thousand sabres under the command of General Kastyurin, included 500 Kazan Tatars [3, p. 250]. On August 18, in Sterkenigen [now Dovatorovka], Apraksin's army joined up with the army of General-in-Chief V. V. Fermor. Here, at the military council, a plan was approved for a new troop deployment for the further movement of the armies to Königsberg via Zaalau [now Kamenskoye]. At this council it was also decided to “send some of the ‘bad horses’ [sick and wounded horses] to Tilsit, Dinaburg [now Daugavpils] and Pskov, and burn the horse harness (apparently from the dead horses)” [3, p. 251]. It must be assumed that the Kazan Tatar detachment was ordered to escort the ‘bad horses’, since until then the ‘team’ had rarely been involved in combat operations as part of the army and had mainly performed patrol and escort duty in the rear [7]. In all likelihood, the Tatar convoy detachment picked up the "skinny horses" in the vicinity of Insterburg, where the wounded and "extra" horses could have been collected after the battles in the Kattenau-Kummeln-Gumbinnen-Insterburg area, and left for Tielse early in the morning of August 20, moving along the shortest route through Zeeslaken [now Pridorozhnoye], Szeerandzen [now Vorotynovka], Rosveche [now Pokrovskoye], Zhillen [now Zhilino] and Zambro [now Zagorskoye]. Soon, the Russian army would also pass through Tielse along this same route after the battle at Gross-Jägersdorf [8, p. 51]. By the evening of the same day, the detachment found itself near Szeerandzen, approximately 30 kilometers from Insterburg, where it encountered a small detachment of "yellow" hussars of the 7th Hussar Regiment of Colonel Malakhovsky [9]. They remained in the rear of the Russian army after Apraksin left Insterburg and, hiding in the surrounding forests, waged a guerrilla war together with the local population. It is possible that the Tatars took the hussars by surprise at Scirandscene itself, sending forward a flying vanguard. This may explain why they, who had not yet participated in the military actions of Apraksin's army and were inferior in armament and training to the Prussian hussars, managed to capture prisoners and emerge from the battle as victors, arriving later in Tilsit with a herd of "skinny horses".

This is the reconstruction of the events preceding the battle at Szeerandszen. No other evidence of the battle, except for the memorial stone in Vorotynovka and the mention of Szeerandszen, the Tatars and the wounded Prussian hussars in the diary of the vice-mayor of Tielse, Rösenick, has yet been found. It is only known that the battle took place on August 20, and the next day the Tatars arrived in Tielse. The distance between Szeerandszen and Tielse, as well as between Insterburg and Szeerandszen, is about 30 kilometers. For a horse convoy with a herd of lame horses, this is quite achievable, considering that the daily march of infantry on a normal march with halts averages 32 kilometers [11, p. 3]. The absence of any mention of Scirandscen by Maslovsky, despite his meticulousness in working with military archives, can be explained by the fact that the “multinational team”, due to its illiteracy and anarchy, most likely did not keep logs of military actions, so there was simply no report on the battle at Scirandscen. Bolotov was near Saalau on August 20 – far from the scene of the event and may not have known about the battle.

List of sources and literature

- Angrapa. Ru . Page of the historical and local history society "White Raven" (Insterburg Castle) URL: https://www.angrapa.ru/kraevedenie/belyj-voron/3088-parad-kamnej-prodolzhenie.html (date of access: 04/24/2021).

- Adrianovskaya M. V., Bardun Yu. D. Unknown pages of the Seven Years' War in East Prussia: the battle at Szeerandszen and the chronicle of events from the diary of Andreas Rösenick // Kaliningrad archives. 2020. Issue 17. Pp. 21–39.

- Maslovsky D. F. Russian army in the Seven Years' War. Apraksin's campaign in East Prussia (1756-1757). Moscow: Printing House of the District Staff , 1886-1891 .

- Rambo A. Russians and Prussians: History of the Seven Years' War. Moscow: Voenizdat, 2004.

- Bolotov A. T. Life and adventures of Andrey Bolotov. Described by him for his descendants. M.: TERRA — TERRA, 1993.

- 6. Thiel EC Statistisch-topographische Beschreibung der Stadt Tielse, Königsberg, 1804. URL: https://books.google.de/books?id=u-8BAAAAcAAJ&pg=PA9#v=onepage&q&f=false (date of access: 24.04.2021).

- Rakhimov R. N. National cavalry in the Russian army: the experience of the Seven Years' War of 1756-1763 // Collection of materials of the scientific and practical conference dedicated to the 80th anniversary of Bilal Khamitovich Yuldashbaev. Ufa, 2008. URL: http://syw-cwg.narod.ru/bshk_syw.html . (date of access: 04/24/2020).

- Golovanova L.D., Kretinin G.V. On the campaign of the Russian army in Prussia in 1757 // Kaliningrad archives. Issue 1. State Enterprise "KG", Kaliningrad, 1998. Pp. 44-63.

- Prussian Front of the Seven Years' War. URL: https://gusev-online.ru/news/obshestvo/19664-prusskij-front-semiletnej-vojny.html#sel=47:4,47:4 (accessed: 24.04.2021).

- Prussian regiments of Frederick the Great. URL: https://vk.com/@sevenyearswar1756-prusskie-gusarskie-polki-fridriha-velikogo (date of access: 24.04.2021).

- Gurov S. A soldier and a squad on a campaign. Voenizdat. 1941. URL: https://libking.ru/books/ref-/reference/116098-s-gurov-boets-i-otdelenie-na-pohode.html (accessed: 24.04.2021).